General practice is a good job. It uses knowledge, experience, judgement and intuition to provide appropriate care and this complex process is both stimulating and rewarding. Currently with rising patient expectations and decreasing investment, solutions to workload issues may benefit from broader thinking and looking to other models of care.

We wish to reflect on our experience of translating care from the NHS in Scotland to Medicare in Australia.

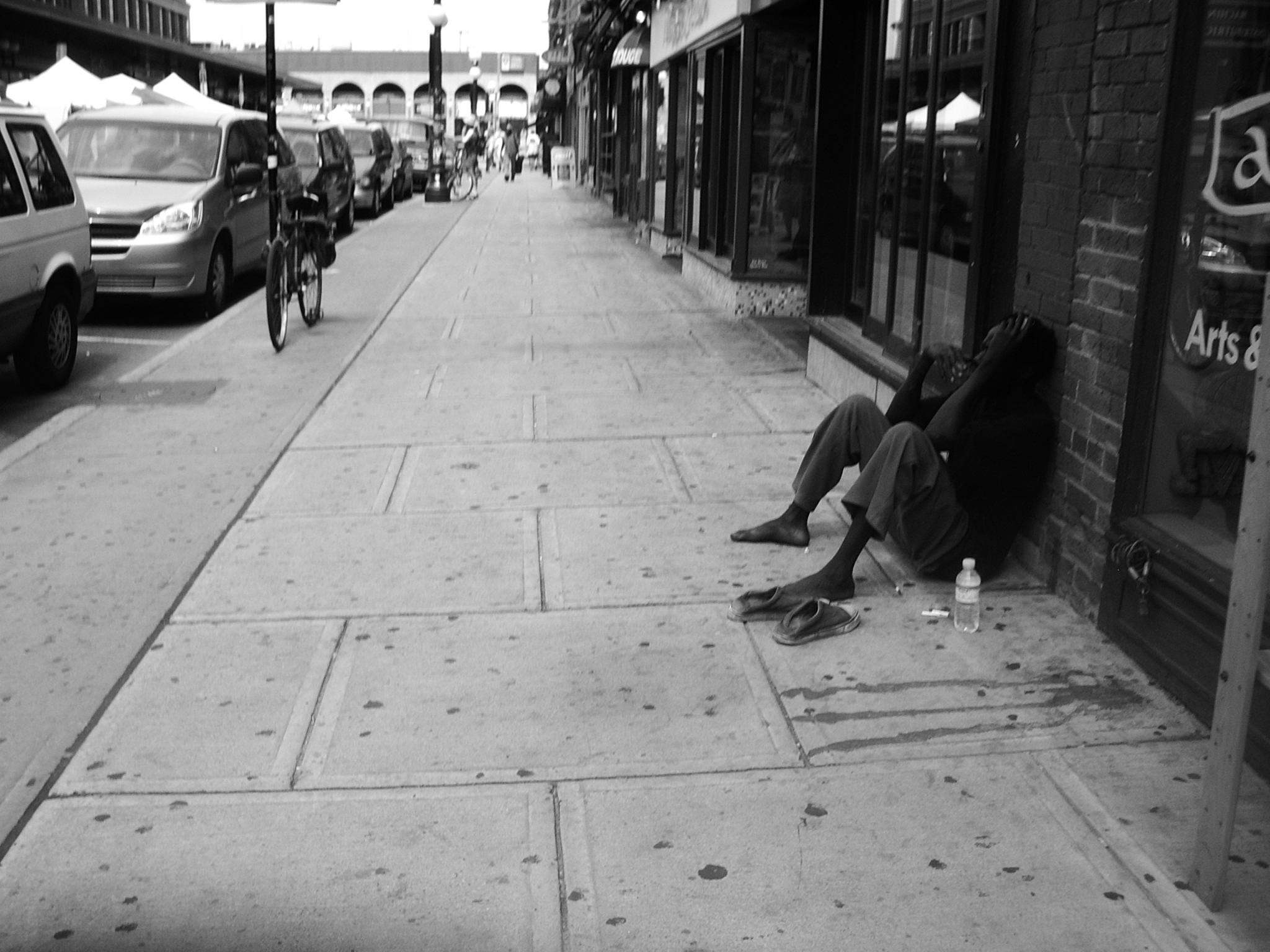

We became emotionally exhausted attempting to continue providing the level of care expected by the population.

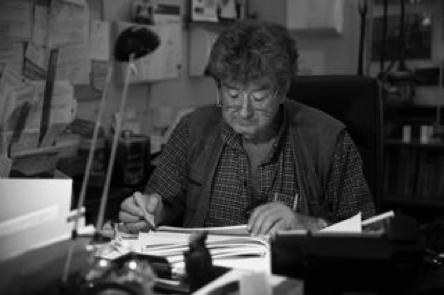

Our background was working as general practitioners (GPs) for 26 years within the NHS model of care based in Stranraer, a small town in Scotland. We knew our patients and their families extremely well. We were truly part of a team with practice nurses, linking with district nursing staff and being part of the community hospital. This involvement provided professional satisfaction and support from a multidisciplinary team. There were many changes over the years and the team structure of General Practice allowed moulding and restructuring to changing demands. However, we became emotionally exhausted attempting to continue providing the level of care expected by the population with decreasing resources and increasing clinical governance. It was hard to manage workload and demand as well as fulfil the QOF (Quality and Outcome Framework) criteria and paperwork. It seemed the fun of the job had decreased with the doctor agenda rather than the patient agenda driving the consultations. We were concerned about moving out of our comfort familiar zone and working elsewhere without the ‘safety’ of background knowledge of patients and relationships that had developed from years of continuity of care.

Could we re-establish our professional satisfaction and feel the fun again of general practice by moving continent?

Adapting to a new model of care has been refreshing and interesting. Firstly, we realised that the therapeutic relationships with patients we value so much and had felt were partly built on years of continuity of care can be established quickly within a consult. This may be aided by years of experience although I do believe that active listening skills are the key. Trust can be felt at the consultation and so it can be a surprise when despite this patients do move around for care. The GP model of care in Australia allows patients to go to any GP practice at any time, so ongoing relationship care is viewed differently by both the patient and the professional.

We have considered the impact of this fundamental difference between the NHS and Australia primary care. The Australian system does encourage patients to take more ownership of their own care although it may result in over servicing and unnecessary repeat investigations. However, the GP is freed from the trapped feeling of patients being dependent on him or her as an individual. Patient autonomy and ability to seek second opinions is almost encouraged and facilitated in Australia. This can be releasing and helpful, although potentially confusing and may result in patients searching for the response desired by the patient. As there is little effective transfer of information or central data base to connect patient information, decisions can be made within silos of thinking.

Perhaps care could be considered in different contexts; acute and chronic. Acute consults sometimes including incidental task oriented requests like forms or repeat prescriptions and ‘chronic’ for more complex ongoing illness review. It appears that some patients seem to value continuity of care for chronic disease, while attending different ‘convenient’ practices for incidental or acute care. In some regard this does make sense as good background knowledge of medication tried and pathology results may be more important for management of chronic conditions.

The flexibility of provider of care allowed to each patient does alter the fundamental role of GP as the hub of the wheel and ‘gatekeeper’ that is strong in the UK model of general practice. The GP is part of the care, but not the truly essential coordinator in Australia. As stated, the care may then be inappropriate or with duplication at times but it can also provide appropriate convenient care, for example, antibiotics for a UTI in a timely and accessible manner at a consult near the where the patient may be shopping. However, there is no real way of stewardship of the public purse which will be providing Medicare back up payments for many visits.

In the NHS… some shift to patients accepting some accountability for their own care would be good to see.

Currently there are ‘care plans’ and ‘team care arrangements’ under the Australian Medicare scheme. These are used for ongoing complex illness and team care is for co-ordinating allied health referrals. This model applies well to some cases – for example patients with diabetes. It does encourage goal setting for individual patients with their ‘regular’ GP and review can be three monthly. The emphasis is focused on the individual patient in contrast to the QOF points in the NHS model which is doctor agenda and population care driven. Also there is current discussion regarding the ‘my medical home’ model in Australia to further incentivise care by one GP. This may help address some of the duplication and rationalise ongoing responsibility. I believe this may be of benefit particularly to the most vulnerable such as mentally unwell patients who may slip through the net. The responsibility by the GP in the NHS can be over-burdensome and some shift to patients accepting some accountability for their own care would be good to see, particularly given the current recruitment crisis of GPs in the UK. This requires understanding from society and a change from people feeling that totally comprehensive care is a right to encouraging capable individuals to play a more active part in their healthcare. GPs may then feel less trapped in impossible positions within the NHS model of care.

A huge learning area for us has been understanding the business financial differences within general practice in the two countries. The curious bit is considering how this affects care delivery both from a patient ‘consumer’ perspective and from the professional point of view. Our practice in Australia followed a ‘bulk billing’ model until recently. This model survived on Medicare rebate income from item of service and was effectively free to patients. Translating across from the NHS, this model fitted our beliefs of having no barriers to accessing primary care. However, we have now a deeper understanding of Australian Medicare and appreciate this government support is essentially present for those who have healthcare cards and so fit the criteria for free care. Interestingly, others often wish to pay their way as part of their expectation and own feeling of self-worth, not misusing the ‘free’ system. This seemed to us an interesting cultural shift from the British feeling of their rights as they have paid taxes to the Australian view where they feel it is appropriate to contribute and often have a higher regard of value when linked to a higher cost. However, there are some patients on the borderline for ‘healthcare cards’ which is the entitlement to free care and so are charged for consults thus may find cost a barrier to seeking appropriate primary health care. Using judgement to allow bulk billing could allow discretion to the most vulnerable but still lacks the guarantee of access to primary care for all. We do believe access to primary care is a fundamental right and it is a professional duty to manage this demand supported by broad discussion with society.

Our view is that there is value in adopting the best of both models of care.

The concept of ‘my medical home’ with continuity of care for patients with chronic illness while still allowing patients to access convenient care for acute problems may be a hybrid that could be considered. Ideally some linkage of electronic health records would support some mobility of patients and safety net patient care, while helping to reduce duplication and unnecessary investigations. This is truly a challenge for health care everywhere.

Moving to Australia has refreshed us professionally and allowed us space to reflect on and appreciate the robust system of general practice in Scotland.

Within the consultation, a focus on patient driven agenda with individual patient health goals is important. This may result in more engagement and accountability by individual patients and some of the dependency which exhausts individual general practitioners would be alleviated. One challenge is how to maintain clinical governance and standards of care within such a wide scope of work. Measuring outcomes can miss valuing the skills of navigating multiple co morbidities and providing appropriate holistic care. Knowledge and skills that are hard to define or measure are key to implementing appropriate individual care.

The engagement with individual patients resulting in improved professional satisfaction is still possible and the fun can certainly bubble up again. Recognition of the importance of primary care and managing public expectations are key to helping the bubbles rise up again. Moving to Australia has refreshed us professionally and allowed us space to reflect on and appreciate the robust system of general practice in Scotland. However, general practice in Scotland would benefit from review to alleviate the exhaustion of unrealistic patient demands and impossible society expectations. General practice is a complex job so any adjustments are complex but without recognition of the value of the job along with adaptation and changes to the job, there is a risk of loss of the essence, fun, effectiveness and professional satisfaction for the next generation.

General practice is still a wonderful job.