Heart of the Nation: Migration and the Making of the NHS. Online exhibition curated by the Migration Museum.

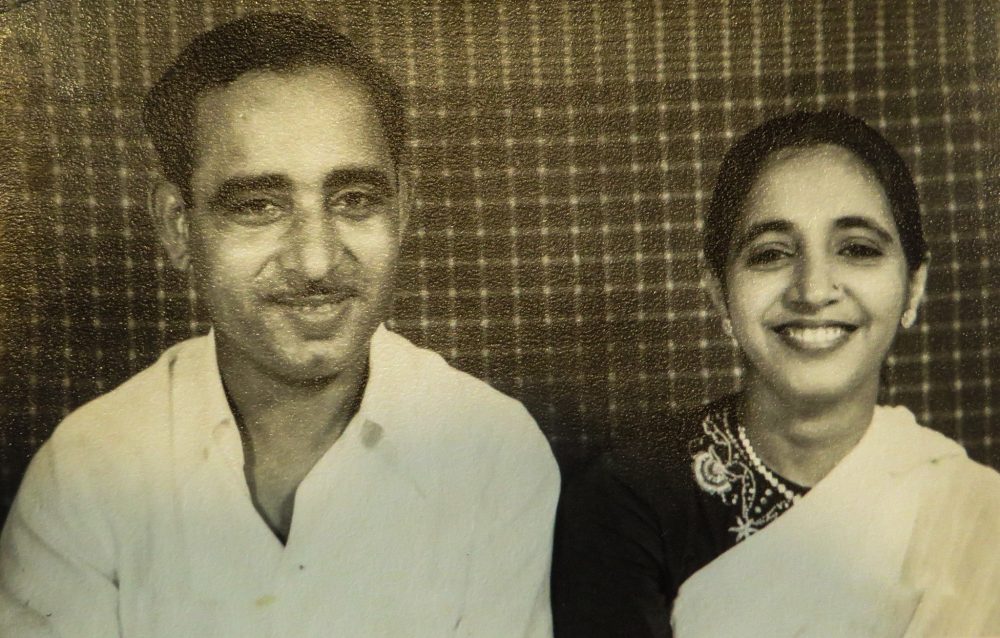

If you had stood at Piccadilly Circus, London, on any Thursday evening at 8pm in December 2020, you will have seen on the large screen an animated video depicting a boat and photographs dancing across the screen. One of the photographs was of a smiling Indian couple with beating red heart between them. These were my parents – see photo above. Men and women in surgical masks appeared, and in large lettering, “The Heart of the Nation”. You would have understood that this was about the NHS and its workers, and how much the NHS is loved by the people of Britain.

The Migration Museum had persuaded the owners of this prime advertising space to give up a five-minute slot to advertise their new online exhibition, The Heart of the Nation. The exhibition describes the contribution of immigrants to the NHS, using their individual accounts of working in the NHS and of living in the UK.

The Heart of the Nation exhibition describes the contribution of immigrants to the NHS.

In the exhibition, a brief history includes the Anglo-Norman monk Rahere who founded St Bartholomew’s Hospital in the 12th century, the seemingly colourful Sake Dean Mohammed (the “Shampooing Surgeon” of Brighton), Mary Seacole, and Henry Wellcome who was a migrant from the USA. A world map shows the number of migrants currently working in the NHS from the various continents.

In the NHS, overall 17% of the workforce is non-UK. A bigger proportion of doctors are immigrants, and a large number (40%) are from BAME background. Their contribution hit the headlines during the Covid-19 pandemic: 95% of doctors who have died with Covid-19 are BAME.1 However, this exhibition is about people, not numbers. What do we know about our migrant NHS workforce? Who are they, where did they come from, what has been their experience of the UK and of working in the NHS?

In the NHS ….. 40% [of doctors] are from BAME background.

The written accounts are from interviews which are quoted selectively but verbatim. The stories are not all about hardships and racism. Zeny Santos, was completely unprepared for the cold weather she experienced on her arrival here in the winter from the Philippines. She was kindly helped by strangers to reach her hospital near Dorset. She felt welcomed, settled, and married locally. She says, “To this day I feel blessed to live here. It has become the home I love”.

Yvette Gordon demonstrates the two-way benefit of migration. Having received her training in nursing and administration here, she returned to Sierra Leone and established a nurse training school in Marampa. She took charge of a military hospital, and was included in the greeting party for our Queen’s visit to Sierra Leone in 1961. She later came back to England and worked as a midwife.

“To this day I feel blessed to live here. It has become the home I love.”

Dr Prakash Sinha, a cricket and chess player, moved to the UK in 1993. He came from “humble roots” even by India’s standards, but worked hard to obtain a medical degree in Mumbai, later becoming a surgeon. He left India to avoid dishonest medical practices in Mumbai – his seniors asked him to perform an appendectomy on a patient who did NOT have appendicitis. He “prioritised ethics and morals over the business”. Dr Sinha contracted Covid-19 while working at the Princess Royal University Hospital, London. He died in October 2020, possibly resulting from a late complication from the Covid-19 infection.

Dr Prakash Sinha left India to avoid dishonest medical practices in Mumbai…

Hargundas Khanchandani, my father, arrived in Carmarthen in 1954. In an audio clip he says he was the only coloured doctor there, the only coloured man most people had met. They knew nothing about Indians. He was astonished that “…people who ruled over us so long did not know our culture.” Although he never openly admitted this, I believe he did not return to India because he did not achieve his goal of passing the MRCP. He could not become a consultant without it, and turned to general practice in 1963.

My father once said, “If there was discrimination, it was in my favour”. This contrasts with my experience. In the sixties, shouts of “wogs go home” from strangers were commonplace. My father told me it stood for “worthy oriental gentleman”, and suggested I take it as a compliment, although we both knew it was an insult. Perhaps my father was the better for being able to rise above it. I recall a potato seller in Leeds market who refused to serve me and my wife, barking, “Go back where you came from.” When I asked, nonplussed, in my south-England accent, “What, you mean Luton?” his scowl only deepened. The very personal nature of that racism still feels viscerally humiliating, even after forty years, partly because not one of the dozens of people nearby supported us. However, since my arrival in the UK in 1963, my experience is that racism has considerably lessened, and much of my life here has been full of supportive colleagues and friends.

The very personal nature of that racism still feels viscerally humiliating.

The exhibition does have examples of overt racism: Allyson Williams, who came to the UK in 1969, says, “[patients] They’d slap your hand away and say, ‘Don’t touch me, your black is going to rub off on me.’ How distressing it must have been for Margaret Jaikissoon (from Trinidad) when many patients “rejected the care of a black nurse” in case “something heinous may occur”. This chimes with my personal experience as a child – once a lady rubbed her finger on the back of my hand to check if my colour came off.

Discrimination in advancement is described in a couple of accounts. Take the experience of Dr Nayyar Naqvi’s in 1968. His job applications were frequently rejected without an interview. However, he goes on, “Any interview that I went to, bar one, I got the job. It was a question of getting to the interview stage.” Failure to obtain interviews remains a persistent complaint of BAME people to this day. Margaret Jaikissoon (in the mid-seventies) found that she was “repeating the same menial jobs, whilst her white counterparts were able to prosper with more advanced jobs”. Her colleagues joked about her cooking and “how she smelt of curry and garlic”. Can we now imagine a British diet without curry and garlic?

The story of ‘Aunt Lotte’ is particularly poignant. At the age of seventeen, in 1938, she was sent by her Jewish family in Czechoslovakia to study nursing in Manchester. Soon after, she discovered that her brother was imprisoned in a concentration camp, but she managed to have him released with the help of a local Mancunian. How wonderful was that! As Britain entered the war, suspicion fell on immigrants and, not so wonderfully, she was forced to abandon her training for a while, before finally becoming a psychiatric social worker. Later, she migrated again, this time to Canada to become professor of social work at McGill University.

Johanna Walsh arrived in England from Waterford, Ireland, in 1955. There are two photographs of her wearing beautiful handstitched dresses which she brought with her, making her look very elegant. She says, “Life wasn’t always a bed of roses”, and one can understand why – those were the days of notices outside rental properties stating, ‘No Blacks, no Irish and no dogs’. In addition, she was an unmarried mother, a huge stigma in those days. What tribulations must she have faced? She became a psychiatric nurse. Now ninety, she is grateful for the services NHS provides for her.

Many immigrants featured here retained strong links with their home countries. Prakash Sinha started a charity which has provided paediatric ventilators and PPE equipment to Indian hospitals. My father, after his retirement, spent up to six months each year in India raising funds and carrying out charitable works.

Margaret Jaikissoon re-established her links with Trinidad after retirement and married her childhood sweetheart from whom she had separated 45 years previously. Yvette Gordon opened a nursing school in Sierra Leone. One of my partners, Dr Sahdev Swain, has for many years been involved with helping to create a much-needed training programme for GPs in India. My own practice, in the nineties, was heavily influenced by the use of lay health care workers in developing countries and established the role of the HCA to help manage chronic diseases and later depression in S.Asian patients who did not speak English.2

Some of the stories were told to curators by the people themselves. Others are told by relatives. I told the curator the story of my father, but based on an interview my daughter, Priya, recorded with him for the BBC’s ‘The Listening Project’. Aunt Lotte’s is told by her nephew, Nick Fox, Margaret Jaikissoon’s by her son. Johanna Walsh’s story is based on conversation with her daughter Catherine Walsh. I suspect they found it as emotional an experience as I did.

Accompanying each story are photographs of the individuals, their families, and their possessions. There are one or two audio and video clips. The exhibition is well put together, easy to navigate. One can dip in and out. The stories can be read by decades, individuals, or by themes which include ‘arrivals’ ‘birth of the NHS’, and ‘making a life in Britain’. Other stories can be added – Johanna Walsh’s account was added after the exhibition began. The stories range from pre-World War II (Aunt Lotte) to the present (Prakash Sinha).

Of course, the accounts do feature racism and hardships, but that is not the message I took away. I saw in these people hard work, determination, resilience, optimism, personal ambition, as well as a wish to do good for society. It is often said how fortunate we are that immigrants come to “serve the NHS”.

However, these immigrants’ primary motivation for migration varied. Some wanted to escape their home country, such as Dr Sinha, and perhaps also Johanna Walsh. Aunt Lotte’s escape from Nazis in Czechoslovakia in 1938 was timely, but tragically her father died in a concentration camp. My father came to take the MRCP, others came to achieve nursing qualifications. All migrants have personal ambitions, want to improve their own and their families’ lives. In the process they do, of course serve the NHS, but then so do all NHS employees.

The exhibition, Heart of the Nation, does not try force feed us a ‘message’. The curators of the Migration Museum could have taken stories of famous migrants, such as Magdi Yacoub, to trumpet the contribution of immigrants. The exhibition is not about trumpeting. It is not proselytising or political. It is not asking us to thank immigrants. These are workaday people, like many of us, whose stories inform us, not only about their experience, but also something of life in Britain. We can also see how internationally connected Britain was and remains.

We can also see how internationally connected Britain was and remains.

The Migration Museum may be open to some criticism. The exhibition does include a few stories of children of immigrants, children born in Britain, but the focus is on first generation immigrants. More of the former may have given us a better understanding of how experiences have changed with time. Nor, of course, do we have stories of white British people who currently work in the NHS. Immigrants face hardships, but what about white British people from deprived communities, do they face similar issues of discrimination? If we are to value the contribution of people who work in the NHS, perhaps we should hear from all parts of British Society.

However, for the moment, let us celebrate Heart of the Nation, because I cannot recall another national exhibition like this featuring the NHS. There are plans to curate a physical exhibition at the Migration Museum once the world opens up.

Heart of the Nation is curated by Aditi Anand. The Migration Museum is at Lewisham Shopping Centre, London SE13 7HB. There are other physical exhibitions which can be viewed once the museum opens again.

Featured online exhibition

Migration Museum. https://heartofthenation.co.uk

References

- BMA, “COVID-19: the risk to BAME doctors,” 13 November 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/your-health/covid-19-the-risk-to-bame-doctors

- Khanchandani R, Gillam S, “The ethnic minority linkworker: a key member of the primary health care team?,” British J of Gen Practice, vol. 49, pp. 993-994, 1999

Featured photo of Dr Hargundas Khanchandani with his wife Shanti, 1954, courtesy of the author.