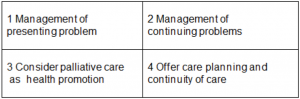

The most formative article I read in GP training 40 years ago was the “Exceptional potential in each primary care consultation”.1 It described a simple practical framework of how to structure routine consultations to potentially cover four important domains – management of presenting problem; management of continuing problems; opportunistic health promotion; and modification of help-seeking behaviour.

This framework has been seminal in mainstreaming opportunistic health promotion in primary care worldwide, and is integrated in medical and nursing education and training in many low and high income countries. Vaccination, family planning, screening for various diseases and life-style advice are now accepted aspects of opportunistic health promotion in primary care, enabled by this simple framework over the last 40 years.

Primary care has the opportunity to integrate palliative care … to prevent suffering in the last phase of life.

Now, highlighted by Covid-19, primary care has the opportunity to integrate palliative care in national health services to promote quality of life and to prevent suffering in the last phase of life.2 But the fundamental barrier to patients not receiving this approach of holistic care and planning ahead is not triggering it early enough in the illness trajectory of all patients with progressive illnesses.3 Misperceptions still exist that palliative care is only for people who are likely to die soon, and only for people with cancer.

This simple model can help. Patients with chronic illnesses often consult primary care with acute episodes but fail to access anticipatory or palliative care. If we prioritise quality of life and health promotion, we can try to allocate a scarce moment to consider if a palliative care approach should be triggered to optimise quality of life and care planning.

Box 1 The potential in each primary care consultation to consider a palliative care approach – an aide-memoir

So to integrate palliative care, first quickly and sensitively deal with the acute problem, such as a chest infection. Then check the impact of any long-term condition(s) on your patient’s welfare. Then consider if your patient might benefit from a palliative care approach. Do this by using your intuition, or ask the “Surprise question” – would I be surprised if my patient were to die in the next 12 months? Or refer to an aide-memoire tool such as the Palliative Care Indicator Guide (PIG), www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk or the SPICT www.spict.org.uk which is now available in 12 languages, including a version for low-income settings and a free App.

UK general practitioners increasingly run computer algorithms to identify and flag up patients for early palliative care, and notes can be electronically tagged in advance to save time.4

Then remembering the fourth box of the model, offer to discuss the likely course of their illness and to start care planning, and to share a summary of their electronic medical records to improve their experience of unscheduled care, by not having to repeat the same story to GPOOH, ambulance service, the emergency department, and at admission. Most patient see the great benefit to them of this. The word “palliative care” can discourage patients, so we call this process “Anticipatory Care” in Scotland. It is increasingly popular, and helps let patients live and die where they want and decrease inappropriate admissions and emergency room attendances.5 If you run out of time, invite the patient back to the surgery, or consider a home visit.

We cannot prevent dying, but we can certainly prevent much unnecessary suffering and overtreatment.

This aide-memoire highlights the potential and provides a structure to try to leave time even in a 15 minute consultation for opportunistic health promotion, and planning care. Prevention is better than cure, even at the end of life. We cannot prevent dying, but we can certainly prevent much unnecessary suffering and overtreatment. Making and taking time to consider this earlier than later is valuable for all concerned.

This is early palliative care for those with any progressive illness. A GP friend of mine said to me “This is just good general practice.” He is right. So it is, but let’s make it from cradle to grave!

References

1. Stott NCH, Davis RH (1979).The exceptional potential of each primary care consultation. JRCGP,(29), 201-5.

2. World Health Organization. Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into Primary Health Care. Geneva; 2018.

3. Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, Moine S, Amblàs-Novellas J, Boyd K. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ. 2017;356.

4. Mason B, Boyd K, Steyn J, Kendall M, Macpherson S, Murray SA, Computer screening for palliative care needs in primary care: a mixed-methods study, Br J Gen Pract. 2018; doi https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X695729

5. Finucane AM, Davydaitis D, Murray SA et al. Electronic care coordination systems for people with advanced progressive illness: a mixed-methods evaluation in Scottish primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(690):e20 LP-e28. https://bjgp.org/content/70/690/e20