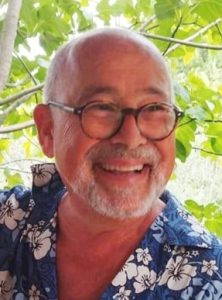

Mark Wallace is a GP, Trainer, and Honorary Senior Lecturer in Oxfordshire. He is the brother of Paul Wallace, who is pictured here.

Mark Wallace is a GP, Trainer, and Honorary Senior Lecturer in Oxfordshire. He is the brother of Paul Wallace, who is pictured here.

In memory of Professor Paul Wallace 27.8.1952 – 28.2.2024

Paul Wallace was first and foremost an academic and teacher but, in parallel with this, practised as a GP, acting as a partner in a Hampstead practice for over 20 years. He was Professor of Primary Health Care at UCL (1993-2012). He was appointed National Primary Care Director for the NIHR Clinical Research Networks in 2006 and was a past President of the European General Practice Research Network. He was awarded the RCGP President’s Medal in 2013. His research interests included reducing harmful drinking, telemedicine and digital healthcare. However, this article is not about recognising his illustrious career but rather, the lessons learnt from his approach to living with a terminal diagnosis that might help improve the experience of other dying patients and those close to them.

Paul was diagnosed with locally advanced prostate cancer in 2019. Unfortunately, it rapidly escaped androgen suppression. Paul was under no illusion about his prognosis and from an early point he openly discussed what his future was likely to hold.*

Against medical interventionism

His frankness about the progression of his disease with colleagues and friends as well as family resulted in an absence of awkwardness and an appreciation by all of what Paul was facing.

Paul was a long-time sceptic of ‘medical interventionism’ for its own sake. As an academic, he was steadfastly grounded in evidence-based medicine but he believed equally strongly in ‘personalised care’1,2 – that an individual’s care should be shaped by that person’s wishes based on informed decisions. He set out very clearly what was most important to him and how these aspirations might be achieved in a document he shared with his close family. Excerpts include the following:

‘…My principal concern will be to maintain the best possible quality of life for myself, my close family and indeed everyone else involved in my care. It is more important to me to be able to derive meaning and joy from my life than to prolong it beyond its natural end.’

‘…To be able to stay active mentally, physically and emotionally for as long as possible’

‘…Make efforts to help me stay in touch with friends, colleagues and members of those communities with whom I have been fortunate enough to be engaged.’

‘Do whatever is possible to enable me to continue to live in my own home, even when this means accepting some additional risks to my health.’

‘…To fade from life through natural causes rather than to have medical battles fought over me for no meaningful purpose. Ask the medical team to simply flick the “off” switch if necessary.’

An advance statement

However, confronting one’s mortality is frightening and most people understandably choose to avoid this uncomfortable contemplation.

The benefits to his family of his ‘Advance Statement’3 document cannot be overstated. From a relatively early point it opened up difficult conversations about inevitable physical decline, escalating pain and Paul’s priorities. His frankness about the progression of his disease with colleagues and friends as well as family resulted in an absence of awkwardness and an appreciation by all of what Paul was facing. In my clinical experience, it is not uncommon for friends to somewhat distance themselves from a dying person borne partly out of fear but also a sense of not knowing if that individual wishes to have contact with them or is embarrassed by their weakened state and so only permits close family to witness them in this condition. Paul made it clear that having friends visit and continuing to work helped maintain his sense of fulfilment and purpose in the world. Indeed, Paul would quip that he’d ask himself each day ‘Dr Wallace, what’s your quality of life score?’ to which he’d answer at least 8/10 until his final few days.

Paul was adamant that he very much desired to die in the familiar surroundings of his own home with his 3 dogs in attendance as well his wife and close family. His wish was granted. Indeed, he was drinking wine and watching a film with family, albeit slightly confused due to marked hypoxia, only a few hours before he passed away.

For Paul, he was in the fortunate position of having a loving and devoted wife as well as close family who could endeavour to ensure his aspirations were achievable. Additionally, he could draw on his intellectual pursuits when his physical abilities declined. Many people have far fewer resources to tap but that should not preclude them from being able to contemplate their illness and think through what their journey might look like. However, confronting one’s mortality is frightening and most people understandably choose to avoid this uncomfortable contemplation. Paul was able to undertake this deeply personal reflection independently but many will require facilitation, be it by a health professional, religious leader or simply a trusted friend or family member. This delicate conversation affords the opportunity to explore, express and document the priorities for that person in the latter stages of their life and there is excellent guidance available.4 It may be unrealistic for GPs to undertake this role themselves due to constraints on their time but raising the topic and signposting to other professionals or agencies would be very valuable. Currently, palliative care team referrals usually occur in the final months but this may be too late for patients to consider how best to maximise the quality of their remaining life once prognosis becomes uncertain. If GPs and specialist teams were more aware of the value of an advance statement it would provide greater opportunity for its timely formulation facilitated by trained staff.

A charter for dying

As was the case with Paul, it is certainly possible to have a ‘good’ death. When appropriate, patients should be encouraged to speak openly about death and their fears of dying, to plan for predictable eventualities and to identify sources of pleasure that maintain quality of life. GPs should consider broaching these conversations with all patients with a limited life expectancy and identify skilled individuals who can help patients cement ideas of what is important to them. Paul was unable to add anything about measures to hasten his own death but, if his physical or emotional suffering had become intolerable, he would undoubtedly have wished to exercise this option. It remains to be seen whether the subject of assisted dying becomes part of professional conversations with the terminally ill in the UK in future.

*Explicit written consent to share this story has been obtained from Paul Wallace’s immediate family members, Photo courtesy of the Wallace Family

References

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/what-is-personalised-care/ [accessed 18/4/24]

- https://www.personalisedcareinstitute.org.uk/what-is-personalised-care-2/ [accessed 18/4/24]

- https://www.macmillan.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/news-and-resources/guides/providing-personalised-care-for-people-living-with-cancer [accessed 18/4/24]

- https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/factsheets/fs72_advance_decisions_advance_statements_and_living_wills_fcs.pdf [accessed 18/4/24]

Featured image by Dan Meyers on Unsplash

Very moving. Paul was a wonderful man and hugely inspiring to all GPs