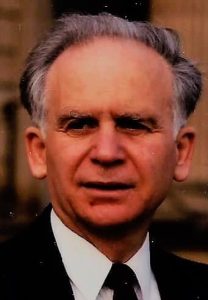

Arthur Kaufman is a former NHS Clinical Psychologist and Medico-legal Expert Witness

Arthur Kaufman is a former NHS Clinical Psychologist and Medico-legal Expert Witness

If only I could get my articles published as I did before the electronics lobby took over.

It’s not that I mind submitting them on line, but getting into print these days, especially on the academic side, the situation is far from ideal. But, before I mutter more moans, I should describe what it was like when I began doing research in the mid-sixties and then having to type-write it all down on what is now known as hard copy, before posting it to a suitable journal while retaining a carbon copy in case it went amiss.

Within a few weeks, I would receive an editor’s reply in a neat brown envelope, either nicely rejecting the paper or offering to publish it, often without the need for alterations.

When it appeared in print some months later, I received fifty or sometimes a hundred free copies of my paper, and an offer of more copies if needed, at a reasonable cost. And within a week, I started receiving handwritten letters and post cards from all round the UK, and later from abroad, asking for a reprint of my efforts, usually from colleagues with similar research interests, who introduced themselves and who seemed pleased to come across a study in line with their own. Requests also came from post-graduate students.

I would receive an editor’s reply in a neat brown envelope, either nicely rejecting the paper or offering to publish it, often without the need for alterations.

If, instead, I asked for reprints from other researchers, I also did so by post and looked forward to receiving them shortly thereafter. In effect, these exchanges not only facilitated exchanges of knowledge, but were done on a personal level, with those on both sides pleased to meet up at conferences, sometimes with invites to visit their respective departments and do a presentation there.

Better still, there wasn’t what has become a deluge of information by internet, with the risk of sudden crashes or destructive viruses waiting to pounce, despite the advantage of sending information at the speed of light, since what is received may not be read for days or even weeks – or not at all – because of the colossal amount of material, much of it not particularly relevant constantly being downloaded into the umpteen gigabyte capacity of modern gadgetry.

I’ve also noticed the increase in the number of authors on many title pages. I gather that this allows each one listed to add to his or her list of papers published, although it doesn’t convey who did what and how much in the research involved.

Even before this practice, it seems that the first or lead author of a paper was not the person who actually did the study and wrote it up, which could have been a junior colleague or even a post-graduate student.

Another problem with what is published today, is what is displayed as abstracts of papers published, along with the use of ‘key’ words to help in locating articles in particular subjects. From what I have read on screen, it seems that the abstract may not accurately reflect what a research paper is actually about, since whoever is doing the abstract may not be qualified in the first instance, or not familiar with the subject matter to start with – in looking up some of my papers published say, over 25 to 30 years ago, I noticed that what has been abstracted has not reflected what the paper is really about, nor abstracted at all despite it having been published shortly after or before a study on the same subject.

Worse still, it seems that if I wish to see to copy of my one of my papers, I may have to pay what is a rather high charge for the privilege, despite my never having signed away my share of, or even my full copyright the paper itself, which, on the face of it, doesn’t exactly facilitate the exchange of knowledge or enable one to fully research relevant studies which have been published years before and which should be cited and discussed accordingly in relation to contemporary research.

In effect, a ‘proper’ review of the literature before embarking on a new investigation may not extend as far back as it should, as though this aspect of ‘history’ ceased in the not too distant past.

…it’s just a dinosaur’s lament. But, from what we know about these creatures, they did relatively well in the survival stakes for around 60 million years or so.

When I describe such difficulties to undergraduates, lots of eyebrows tend to be raised. I recall one student, who listened to what is described in the text so far, coming up to me, and saying that with his interest in a research career, he felt regret at not having been born much earlier. He also not only looked sad and seemed well aware of the pressure on young (and not so young) academics not only to ‘publish or perish’ but the need or perhaps the ‘must’ to do and within the current ‘rules’ if one wants to move up where both promotion and higher income are concerned.

But, as the title of this draft reads, it’s just a dinosaur’s lament. But, from what we know about these creatures, they did relatively well in the survival stakes for around 60 million years or so.

Adapted with permission of author and the Society of Medical Writers: This lament first appeared the Autumn 2019 issue of The Writer, the journal of the Society of Medical Writers.

Featured image by Jon Butterworth on Unsplash