David Shiers is a carer for his daughter with severe mental illness.

Gordon Johnston is a person with lived experience of severe mental illness.

Vishal Aggarwal is a dentist and clinical associate professor at the University of Leeds.

Carolyn A Chew-Graham is a GP and professor of general practice research at Keele University.

We all know that the life expectancy of people with severe mental illness (SMI) is reduced by 15–20 years compared to the general population. The higher mortality rates are driven by physical health comorbidities including heart disease, obesity, and diabetes, worsened by lifestyle behaviours and metabolic side-effects of antipsychotic medication, as well as reduced access to adequate health care.1

Moreover, the mortality gap is widening the trend, mainly due to cardiovascular disease (CVD), now the single biggest cause of premature death in people with SMI.2 In her 2012 James Mackenzie Lecture to the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) annual general meeting, the late Helen Lester encouraged GPs to make people with serious mental illness their core business by not just screening but also intervening.3

What is less well known is that people with SMI also experience serious inequalities in oral health, with high rates of tooth decay, gum disease, and tooth loss (see Box 1). This can affect daily life including with basic activities such as eating and speaking.

Poor dentition can impact on a person’s confidence and self-esteem; it can interfere with relationships or the ability to get and keep a job. This, in turn, impacts on mental health and a vicious cycle ensues. Poor oral health can also increase risks associated with other health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease (which are already increased in this population).4 This means that people experiencing SMI may be dealing with multiple health problems at the same time that are exacerbated by poor oral health.5

| Box 1. Oral healthcare factors associated with people with severe mental illness compared to the general population |

|

The Right to Smile

The Right to Smile consensus statement9 arose from the Oral Health and Primary Care special interest groups established by the Closing the Gap Network, a UK Research and Innovation-funded initiative to develop a mental health network exploring ways to reduce the health gap faced by people experiencing SMI.10

Our Oral Health special interest group comprises people with lived experience, carers, mental health practitioners, dental professionals, researchers, and policymakers. Our ambition is to reduce the inequalities in oral health faced by people experiencing SMI. The Right to Smile consensus believes that tackling this inequality is overdue and deserves urgent attention from services across primary, specialist, and social care, researchers, and policymakers.

The Right to Smile consensus statement has been endorsed by several important bodies including the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Psychosis Research Unit, Office of the Chief Dental Officer of England, World Dental Federation (FDI), a number of voluntary sector organisations, and supported by collaborating universities. We are hoping that the RCGP will endorse this important piece of work and encourage primary care to consider oral health in patients with SMI registered with their practices.

What is/should be the role of primary care?

We outline where opportunistic advice can be given to people with SMI, about oral health, in primary care (see Box 2). We can make a difference to this vulnerable group of patients — improving their quality of life and reducing health inequalities — the core business of general practice.

| Box 2. Opportunities to discuss oral health in primary care |

|

References

1. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6(8): 675–712.

2. Hayes JF, Marston L, Walters K, et al. Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000-2014. Br J Psychiatry 2017; 211(3): 175–181.

3. Lester H. The James Mackenzie Lecture 2012: bothering about Billy. Br J Gen Pract 2013; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X664414.

4. Larvin H, Kang J, Aggarwal VR, et al. Systemic multimorbidity clusters in people with periodontitis. J Dent Res 2022; 101(11): 1335–1342.

5. Kang J, Palmier-Claus J, Wu J, et al. Periodontal disease in people with a history of psychosis: results from the UK biobank population-based study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2022; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12798.

6. Choi J, Price J, Ryder S, et al. Prevalence of dental disorders among people with mental illness: an umbrella review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022; 56(8): 949–963.

7. Turner E, Berry K, Aggarwal VR, et al. Oral health self-care behaviours in serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2022; 145(1): 29–41.

8. Jayatilleke N, Hayes RD, Chang C-K, Stewart R. Acute general hospital admissions in people with serious mental illness. Psychol Med 2018; 48(16): 2676–2683.

9. Aggarwal V, Bateson C, Chew-Graham C, et al. The Right to Smile consensus statement. 2022. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/spectrum/Oral_Health_Consensus_Statement.pdf (accessed 13 Jan 2023).

10. University of York. Closing the gap: about us. https://www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/closing-the-gap/about-us (accessed 13 Jan 2023).

11. Public Health England, NHS England, Health Education England. Making Every Contact Count (MECC): consensus statement. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/making-every-contact-count.pdf (accessed 13 Jan 2023).

12. British Medical Association, NHS England. Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for 2021/22. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/B0456-update-on-quality-outcomes-framework-changes-for-21-22-.pdf (accessed 13 Jan 2023).

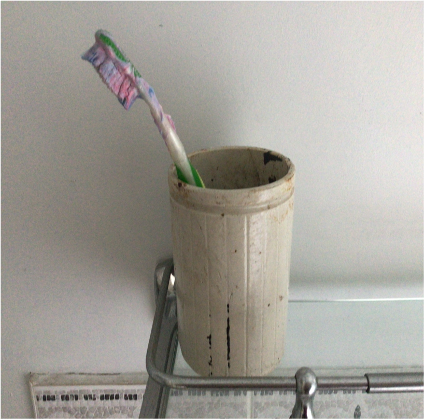

Featured photo, Toothbrush that should prompt questions about oral health by David Shiers, 2022.