As a general practitioner (GP) and a training programme director, I’ve found that engaging with the humanities often reveals surprising insights into clinical practice. We have screened films to help GP trainees explore perspective-taking, visited galleries to sharpen observation, and attended theatre productions to understand the nuances of human stories. These experiences, seemingly distant from the consulting room, can illuminate the subtle dynamics of the doctor-patient relationship. My trainees recently arranged a group trip to see Waiting for Godot.1 In the debrief afterwards, we talked about how the characters’ waiting and their vague, half-articulated hopes echoed many patients in primary care—individuals who struggle to voice their concerns clearly, who long for help but can’t always say how or why. That discussion stayed with me, prompting me to consider more deeply how art—especially “challenging” art forms that embrace uncertainty and improvisation—can help us better understand the consultation itself.

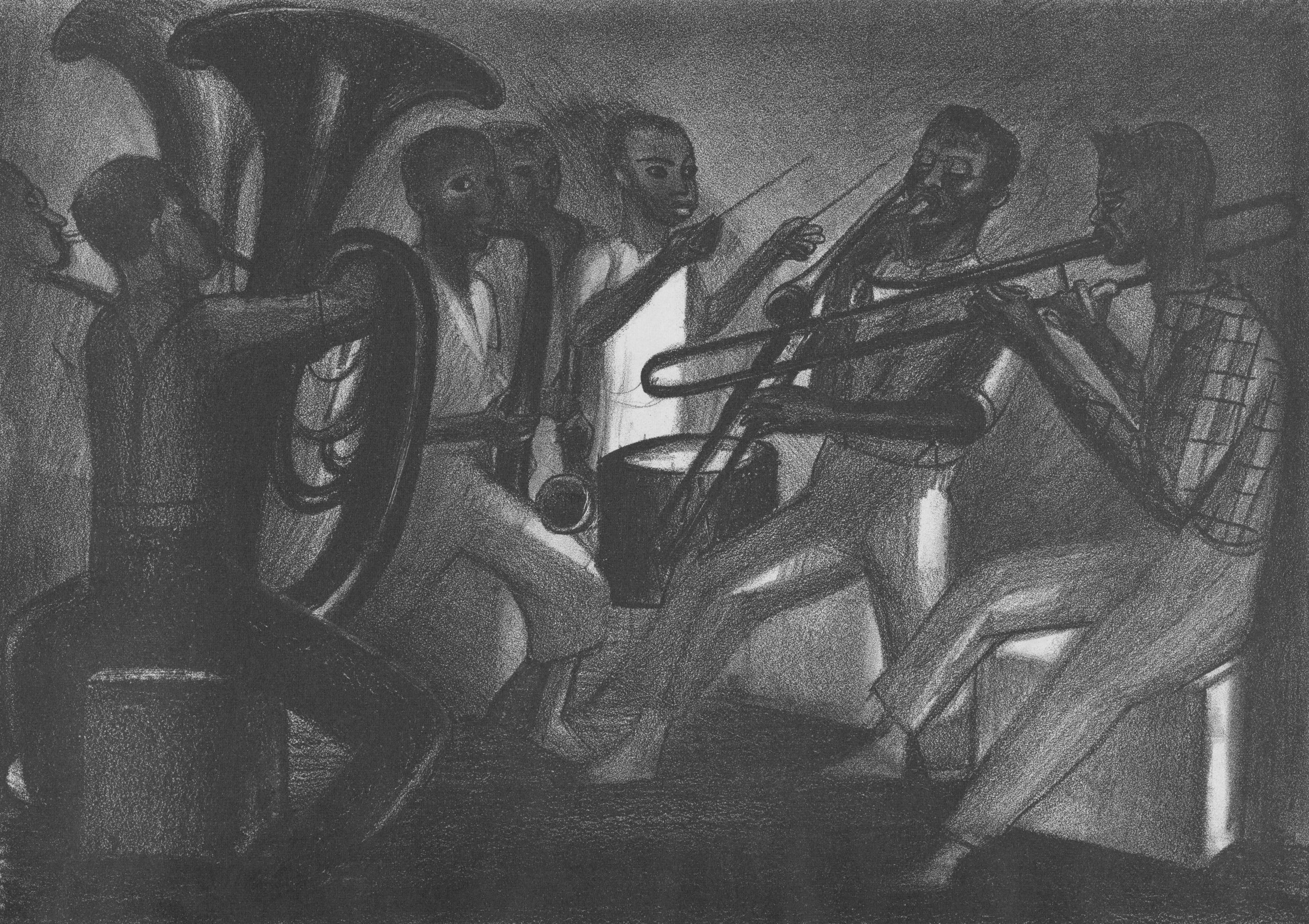

Jazz, like the consultation, is a practice fundamentally shaped by silence, listening, and shared creation.

Outside my medical career, I am also a semi-professional jazz saxophonist. This parallel life in music has, perhaps inevitably, begun to intersect with my thinking about medicine. Jazz, like the consultation, is a practice fundamentally shaped by silence, listening, and shared creation. It asks musicians to take risks, to move beyond mere imitation, and to cultivate an inner awareness of what feels true in the moment. It is a discipline that thrives on spontaneity yet demands deep knowledge and preparation. These are qualities, I believe, that have a profound relevance to the art of clinical practice. I’ll explore these parallels—silence, listening, risk-taking, co-creation, the journey to authenticity, and the role of an inner voice—and consider how they might inform the way we consult and teach.

Silence

In the pause between musical notes and phrases, silence is not emptiness but a reservoir of potential. It carries the weight of what might be played, the delicate tension of an idea poised to emerge. The skilled musician understands that silence is not merely an absence but a crucial element of the music, providing contrast, tension, and ultimately, meaning. Rushing to fill this space could be to diminish the music’s flow, to stifle the unexpressed possibilities that hover in the air. During a consultation, silence can serve a similar purpose. Instead of rushing to speak, to fill the space with our own questions and assumptions, allowing a small pause can help both doctor and patient sense what remains unsaid, what lies beneath the surface of the initial presentation.

In the pause between musical notes and phrases, silence is not emptiness but a reservoir of potential.

This quiet interval might let the patient find the right words to express a complex feeling or a hidden worry, or it might give the doctor time to recognise a subtle emotional cue—a slight hesitation, a change in tone, a fleeting expression—that could easily be missed in a rushed interaction. By honouring silence rather than fearing it, we transform stillness into a creative medium—one that lets deeper truths surface and offers both parties a chance to feel genuinely heard and understood. These moments of pause, though brief, can shift the entire tenor of an encounter, moving it from a routine, perhaps even superficial, exchange to one that feels more meaningful, more connected, and perhaps more revelatory. It allows the consultation to breathe, to become a space where something unexpected and deeply meaningful might occur.

Listening

Listening in jazz goes far beyond simply taking turns or following the predetermined script of a song’s chord changes. Even if one musician is improvising a solo, the others are not merely passive accompanists; they are actively listening, subtly influencing the flow of the music. They offer gentle harmonic hints, suggest rhythmic variations, or nudge the soloist toward unexplored melodic territories. Sometimes this interplay is supportive and consonant, creating a sense of seamless unity; at other times, it is intentionally challenging, introducing dissonance or unexpected rhythmic shifts that push the music into new and unexpected contours. It is through this dynamic exchange, this constant conversation between the musicians, that the music truly comes alive. In a consultation, listening works on similarly multiple levels. The doctor may lead the conversation, asking questions and guiding the narrative, but the patient’s tone, pauses, or fleeting expressions can and should reshape the direction of the encounter.

Genuine listening means allowing the patient’s concerns, however inchoate or tentatively expressed, to guide how we respond, what questions we ask next, and what emotional tone we adopt. Both jazz and medicine teach us that truly attending to another voice—whether a drummer’s subtle shifts in rhythm that propel a soloist forward or a patient’s hesitant disclosure of a deeply personal fear—can yield insights that careful planning alone would never uncover. This deep listening, this willingness to be influenced and changed by what we hear, creates a space where both participants, doctor and patient, can discover unexpected paths to understanding. It transforms the consultation from a one-way transmission of information into a collaborative exploration, a shared journey toward meaning.

From imitation to authenticity

Jazz musicians begin by absorbing scales, transcribing solos, and mimicking the masters. These early efforts are essential; they provide the necessary scaffolding, the building blocks upon which a personal style can eventually be constructed. However, meticulously learned lines and patterns, while accomplished, remain lifeless and unconvincing if they are never adapted to the unpredictable context of real performances with real musicians. Over time, the developing musician begins to experiment with these borrowed phrases onstage, testing them out in different settings, discovering which ideas flow naturally in the heat of the moment, and discarding those that feel forced or out of place. A personal style emerges through this interplay of practice-room technique and the messy unpredictability of live collaboration, through a process of trial and error, of listening and responding.

Similarly, a GP trainee might start by consciously or unconsciously echoing their mentor’s phrasing, adopting their mannerisms, and even mirroring their body language when interacting with patients. At first, these borrowed approaches offer a sense of reassurance and structure, providing a framework for navigating the complexities of the consultation. Yet as the trainee gains experience—encountering a diverse range of patient narratives, personalities, and emotional currents—they begin to refine these templates, discarding what doesn’t fit their own emerging style and shaping what does until they gradually find their own authentic clinical voice. This evolution from imitation to authenticity marks a crucial development in both musical and clinical maturity. It is a process of moving from reliance on external models to the development of an inner confidence, a trust in one’s own judgement and intuition, honed through experience and reflection.

Risk-taking

In improvisation, a musician who never ventures beyond familiar tunes and well-rehearsed patterns will inevitably produce music that is technically proficient but ultimately predictable and uninspired. True artistry arises when the player dares to deviate from the established path, to take risks—perhaps by exposing a raw emotional vulnerability through their playing or by abandoning themselves to the energy of the moment —in order to discover something new and unforeseen. Such risks may not always succeed; they can lead to moments of awkwardness or dissonance. However, it is precisely within these moments of uncertainty that beautiful musical discoveries often occur. Likewise, in the consultation, a doctor might sense that the patient’s halting words hide a more vulnerable story, a hidden concern that lies beneath the surface of their presenting complaint.

In improvisation, a musician who never ventures beyond familiar tunes and well-rehearsed patterns will inevitably produce music that is technically proficient but ultimately predictable and uninspired.

Gently following this hunch, even if it means straying from the standard line of questioning or venturing into emotionally charged territory, can unearth crucial insights that would otherwise remain hidden. Perhaps the doctor acknowledges a tension in the patient’s tone or addresses a fear the patient never fully voiced. This may feel risky—what if it opens an uncomfortable topic? Yet without such forays, the conversation can risk remaining superficial, failing to address the patient’s underlying needs and concerns. Thoughtful risk-taking, guided by empathy and clinical judgement, can lead to more candid, more revealing, and ultimately more connected discussions that neither patient nor doctor might have anticipated or reached by staying on safe, predictable ground. It is about trusting that subtle, pre-verbal awareness, that often precedes conscious thought, to guide the conversation in a direction that feels both authentic and possibly transformative.

The inner voice

Avant-garde jazz pianist Cecil Taylor, a pioneering figure known for his radical approach to improvisation, once offered a profound insight into the creative process. He posed a question that gets to the heart of where music truly originates:

“Is the secret in the symbol of the note, or is it the feeling that exists before you translate the note into music? Music proceeds from within. The note is merely a rather uninteresting symbol that equates to the sound. But sound is always with us.”2

Taylor suggests that the essence of music lies not in the technical execution of notes but in the pre-verbal, inner “sound” – the feeling, the intention, the intuitive impulse that shapes the musician’s choices. This seemingly abstract concept has profound implications for our work as clinicians, for it speaks to the importance of the “inner voice” that guides our perceptions, judgments, and actions. The listener to the music might focus on the notes, but it is the inner sound which gives the note its meaning. Similarly, listening back to a consultation, one might focus on the specific words spoken, but forget about the importance of the inner sound which gave them their shape.

In the context of a consultation, this “inner voice” manifests as the subtle, often pre-conscious awareness that informs our interactions. It is the “gut feeling” that something is amiss, the intuitive sense of a patient’s unspoken anxiety, or the barely perceptible shift in our own awareness that signals a potential bias. This inner landscape is not merely about conscious thoughts or analysis; it encompasses our emotions, intuitions, biases, and even physical sensations. It shapes how we perceive the patient, their story, and their needs, often before we’ve formulated a single question or articulated a diagnosis. A doctor burdened by stress might misinterpret a patient’s reticence as disinterest, their own internal state coloring their perception. Conversely, a doctor who is more centered and self-aware might recognize that same reticence as fear, their inner clarity allowing for a more accurate assessment. This pre-verbal awareness influences our split-second decisions, our reactions, and the overall tone of the consultation. The relationship between the inner sound and the expressed note (or word) is complex and dynamic. While a close connection between the inner voice and outward expression can lead to authentic and effective communication, an unfiltered expression of our internal state might not always be appropriate or beneficial. Navigating this delicate balance is part of the art of both jazz improvisation and clinical practice. This awareness also extends to recognizing our own biases and assumptions, particularly those stemming from differences in cultural and language background. In my work in a diverse community, I’ve become increasingly aware of how my own perspective might differ from that of my patients, and how crucial it is to actively listen for and address those differences with sensitivity and respect.

Developing this capacity for inner attentiveness, for recognizing and reflecting upon our own internal landscape, is a vital aspect of becoming a skilled and compassionate clinician. Just as Taylor believed that authentic music arises from an inner “sound,” so too can our clinical interactions be more genuine and effective when we are attuned to our own internal landscape, both its wisdom and its capacity for distortion. By cultivating this awareness, we become more present, more attuned to the nuances of each encounter, and ultimately more responsive to the individual needs of each patient.

Conclusion

The parallels between jazz improvisation and clinical practice offer an intriguing lens through which to view our daily work. Like other explorations in medical humanities—whether through literature, theatre, or visual art—this comparison invites us to think differently about what we do. By considering how musicians balance structure with spontaneity, how they listen and respond, how they develop their authentic voice, we might find fresh perspectives on our own clinical practice. This is not merely an abstract exercise, but a practical framework that can be integrated into our daily interactions with patients. By consciously incorporating moments of silence, by practicing deep listening, by striving for authenticity in our communication, and by thoughtfully embracing calculated risks, we can enhance our ability to connect with patients on a deeper level. Moreover, by cultivating an awareness of our own inner landscape—our emotions, biases, and intuitions—we can become more attuned and responsive clinicians. This jazz-inspired approach encourages us to view the consultation not as a static procedure but as a dynamic and evolving art form, one that requires both technical skill and a deep appreciation for the human element at the heart of medical practice. It reminds us that the art of healing is a continuous process of learning, adaptation, and improvisation, much like the art of jazz itself.

References:

- Beckett S. Waiting for Godot. London: Faber & Faber; 1954.

- Williams R. ‘In the Brewing Luminous’. The Blue Moment [blog]. 19 Jul 2024. Available from: https://thebluemoment.com/2024/07/19/in-the-brewing-luminous/ [Accessed 22 Jun 2025].

Addendum 1: Practical Exercises for GP Trainers

Silent Observation Task: Have the trainee commit to a few seconds of silence after each patient response during a consultation or role-play. Debrief on how this small shift changes their sense of the patient’s narrative and their own questioning style. Discuss how even brief pauses can create space for deeper understanding to emerge.

Reflective Silence Exercise: After discussing a patient scenario or watching a video recording together, pause deliberately for 15-30 seconds before asking the trainee for their thoughts. Explore how these extra seconds might reveal subtler layers of understanding, allowing both the trainee and the trainer to access their intuitions and pre-verbal impressions.

“Inner Sound” Journaling: Encourage the trainee to jot down their impressions, feelings, and intuitions immediately before watching a recording of their consultation or engaging in a role-play. Afterwards, compare the pre-verbal sense they noted with what they see and hear in retrospect. Discuss how their inner state might have influenced their interaction with the patient.

Risk and Reward Discussion: After observing a trainee consultation, identify a moment where a slightly riskier question or approach might have opened new understanding. Discuss how this parallels improvisers venturing beyond rehearsed patterns. Consider specific examples:

- “Instead of asking ‘How long have you had this pain?’, what if you asked ‘What worries you most about this pain?'”

- “Instead of saying ‘It sounds like you’re stressed,’ what if you said ‘I wonder if there’s something more going on that you’re finding hard to talk about?'”

- “Instead of asking, ‘Do you have any other symptoms,’ what if you asked, ‘What else is on your mind today?'”

- “Instead of asking ‘Have you told others about this?’, what if you asked ‘How have others responded, and how does that feel?’”

Discuss the potential benefits and drawbacks of taking such risks in the consultation.

Art and Ambiguity Reflection: Ask the trainee to recall encountering challenging art and how they felt in the face of uncertainty. Compare this to consultations where patients struggle to articulate their needs, reinforcing that ambiguity can prompt deeper listening rather than hurried resolution.

Addendum 2: Recommended Listening

- Miles Davis – “Fall” (from Nefertiti, 1968) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmWX1erp_u4

“Fall,” a Wayne Shorter composition, is a soft, introspective meditation. The horns converse in hushed tones, each note deliberately placed, allowing space to have its own weight. Davis’s trumpet is thoughtfully sparse, while Shorter’s saxophone interjects with flurries, cries, and pauses. A recurring unison figure, played by the horns, reappears like a murmured agreement in a conversation. Drummer Tony Williams’ initially understated accompaniment gradually evolves, introducing a more assertive pulse. This subtle shift creates movement beneath the soloists, inviting exploration without disrupting the contemplative mood. “Fall” shows how silence and space, combined with subtle shifts in rhythm and dynamics, create a rich musical landscape, inviting the listener to discover deeper currents beneath the surface.

- Sonny Rollins – “There Will Never Be Another You” (from There Will Never Be Another You, 1965) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7GL462lT56Q

This live recording, despite its technical imperfections from Rollins’ restless stage wandering, captures the saxophonist at his adventurous best. His masterful improvisation on this 1940s popular song weaves between careful restatements of the melody and explosive cascades of notes, while throwing unexpected challenges at his band – an unrehearsed key change, false endings, and an impromptu shift into calypso rhythm. Billy Higgins’ drums, prominently recorded, showcase both sympathetic support and feisty opposition, especially during their trading sequences. It’s a thrilling example of risk-taking in action, where a master improviser pushes both himself and his band into unexpected territory.

- Ahmad Jamal – “I Love Music” (from The Awakening, 1970) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fW8NQgqYoVQ

“I Love Music” begins with Jamal’s solo piano, a captivating exploration of the melody’s possibilities. He treats silence as a musical element in its own right, letting notes hang in the air, drawing the listener into the spaces between. Each variation of the theme is a study in contrasts—a cascade of notes followed by a pregnant pause, a delicate phrase answered by a resonant chord. When the trio enters, they embrace this interplay of sound and silence. Bass and drums slip between the piano’s notes, adding subtle textures and rhythmic accents. They shape the music through a dialogue where a brush of a cymbal or a quiet pluck of a bass string is as significant as a more assertive statement. It is the kind of listening that respects what each voice brings and leaves room for the unexpected to surface.

- Lester Young – “Pennies from Heaven” (from Pres in Washington, recorded 1956) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nuYOg62EyuE&list=PLbfjxgSEPUJd6jQt-6IoJzFgTqc8lEpwS

By the time of this late-career recording, Lester Young’s playing was pared down to its essence. His enigmatic phrasing – half-spoken, half-sighed – transforms this standard into an intimate conversation, leaving room for the listener’s imagination. The local pick-up band follows suit, providing sensitive support, allowing space for Young’s quiet reimagining of the tune. They never intrude, simply framing his reflections as he lingers over familiar notes. This unhurried approach suggests that depth comes not from constant elaboration but from the nuances of expression. It’s a beautiful illustration of how a profoundly individual voice can emerge even within the framework of well-known material, a lesson in authenticity: one does not always need to show everything they know. Instead, being true to one’s inner voice—saying what matters and no more—can yield profound resonance.

- Charlie Haden – “La Pasionaria” (from The Ballad of the Fallen, 1983) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QRrP4LfYNW0

Inspired by the Spanish Civil War, this powerful Carla Bley arrangement showcases bassist Charlie Haden’s ability to blend political conviction with profound musicality. The piece begins with a delicate solo guitar introduction, which leads into a stirring folk song-like theme played in unison. This then gives way to an impassioned improvisation by tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman. His emotive power and distinctive sound are a forceful voice against the responses and protests of the ensemble. The group’s interaction throughout demonstrates the kind of sophisticated listening and response explored in the article, creating a moving balance between composition and freedom, structure and spontaneity.

- Cecil Taylor – “The Question” (from For Olim) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFKjdJU9hkk&list=PLb4WoGcUFQfUKsglH6F3H8Ig1nYizJtFK&index=8

In contrast to the other tracks featured here, Cecil Taylor’s piano improvisations are entirely free, unconstrained by predetermined melodies or harmonies. His music can be a demanding listen, even for experienced jazz aficionados, with improvisations often extending beyond an hour. “The Question” (from For Olim), a rare piece under five minutes, offers a glimpse into his radical approach. A powerful example of Taylor’s unique approach to the piano, this brief, intense piece was recorded live and dedicated to his collaborator Jimmy Lyons. Taylor’s playing here is a torrent of percussive clusters and intricate rhythms, seemingly chaotic yet governed by a deep internal logic. This track exemplifies Taylor’s belief that music originates from an inner “sound,” a pre-verbal impulse that transcends the written note. It’s a challenging yet rewarding listen that demonstrates how technical mastery can be harnessed in service of pure creative expression.

- Charles Mingus – “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting” (from Blues and Roots) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGJrFslQ4q4

“Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting” from Blues and Roots captures the vibrant energy of a gospel church service, fueled by a raucous 6/4 groove and Mingus’s characteristic shout that opens the piece. The horns engage in spirited call-and-response, evoking a lively discussion, while Mingus’s bass and Horace Parlan’s insistent piano drive the music forward. Mingus’s unique approach to rehearsals, often eschewing sheet music and teaching his musicians their parts by ear, played a crucial role in creating the band’s dynamic sound. This method fostered a deep internalization of the music and encouraged spontaneous interaction, as exemplified by Parlan’s stuttering figure that ignites one of many explosive ensemble passages. This track is a testament to what can happen when all participants feel free to respond genuinely, each adding their unique perspective, much like an empathetic clinical encounter where shared understanding emerges from open engagement.

Featured Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash