Richard Armitage is a GP and Honorary Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham’s Academic Unit of Population and Lifespan Sciences. He is on X: @drricharmitage

Richard Armitage is a GP and Honorary Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham’s Academic Unit of Population and Lifespan Sciences. He is on X: @drricharmitage

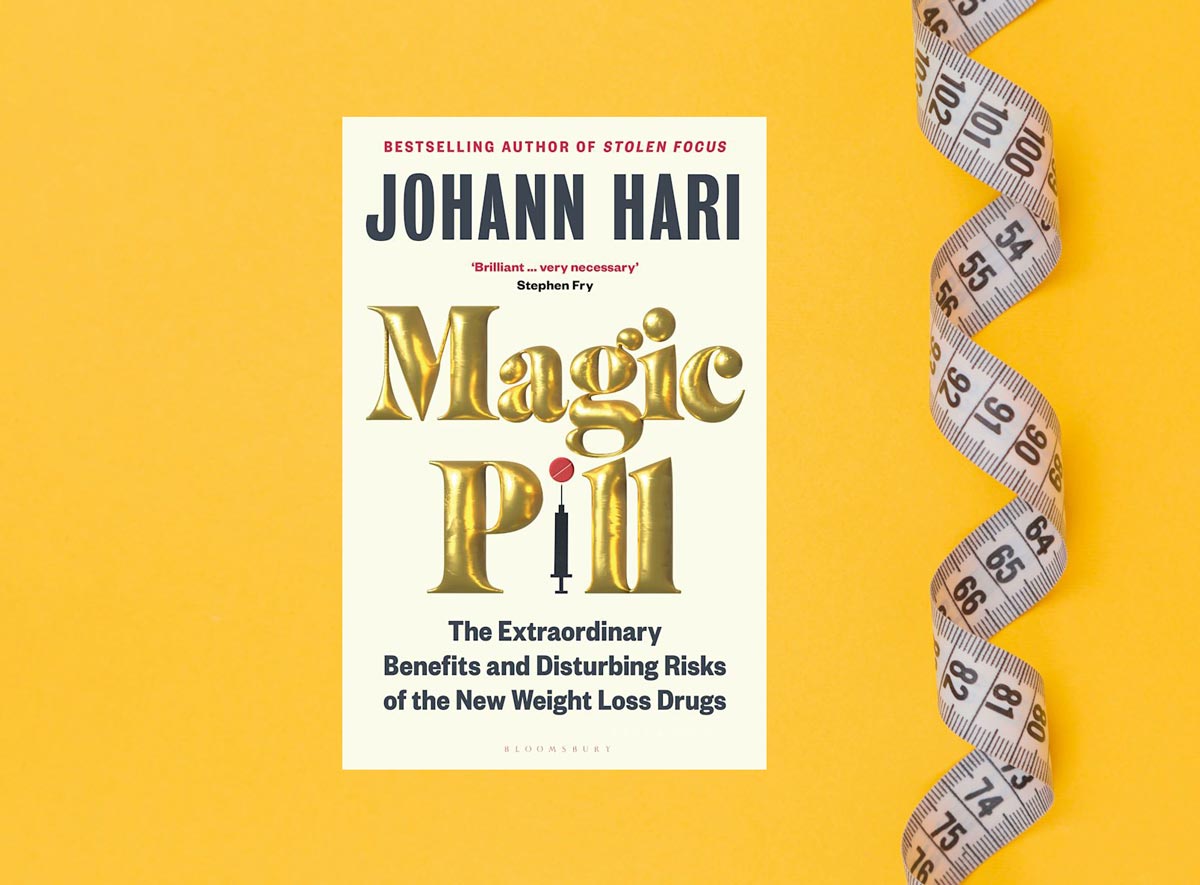

Public awareness of semaglutide — widely known as a ‘weight loss jab’1 — has skyrocketed in recent years. This novel pharmaceutical — which binds to, and activates, the GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) receptor to increase insulin secretion, suppress glucagon secretion, and slow gastric emptying — is now available on the NHS as Wegovy (licenced for weight management) and Ozempic (licenced for type 2 diabetes mellitus).2 While Nada Khan recently explained what GPs need to know about this molecule,3 Johann Hari has produced a book-length treatment of the subject for both the engaged layperson and the curious GP.

In Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight Loss Drugs, Hari unleashes his characteristic blend of personal stories, expert interviews, and masterful story-telling to outline the rise of the latest weight loss pharmaceutical. Drawing on his own struggles with obesity for most of his adult life — which he shares openly with the reader as a vehicle for describing the appeal of these drugs — Hari describes his own experiences of using semaglutide, and those of many others who use (and often had to abruptly stop using) this pharmaceutical. He explains the countless interviews performed with the scientists who developed the molecule and the medics who prescribe it, and outlines the animal and clinical studies that were key to its discovery and development.

“… while we could use this drug to immediately address a serious problem … should we do so?”

Hari provides a brief history of previous iterations of ‘weight-loss drugs’ (which were almost all eventually withdrawn due to safety concerns) before explaining the history of GLP-1 agonists and the subsequent rise of Wegovy and Ozempic. Given my familiarity with the subject from the consulting room, I overlooked the chapter that describes the health risks associated with obesity, but briefly skimming these pages suggested the subject was given a thorough treatment suitable for the layperson.

Hari then outlines the profound changes that have taken place in food manufacturing in recent years — the shift to highly processed foods that reduce satiety and increase calorie intake — which have contributed to the obesogenic environment that is driving the dramatic rise of obesity prevalence across the West.

He then explains the clear clinical benefits of semaglutide for weight loss (and also potentially in the treatment of addiction to substances other than food) before outlining the known and unknown risks, including the association with mood disorders.

He describes the fact that semaglutide studies were conducted using only obese participants, meaning the molecule’s risk profile when used in individuals with a healthier body mass index (as is increasingly the case in the US and in the private sector) might be profoundly different and is, currently, unknown.

“… I found this book to be an easy-to-read and engaging overview of the current weight-loss drug landscape.”

He also outlines the concern over how this compound might be abused, and what it might do to the prevalence of eating disorders. He then contrasts the food landscape and eating norms of the West with those of Japan, which enjoys obesity rates that are a fraction of those of the US and UK, and suggests that navigating towards a Japanese-style arrangement would be a healthier and more sustainable means by which our obesity crisis could be tackled.

Overall, I found this book to be an easy-to-read and engaging overview of the current weight-loss drug landscape. For me, the most interesting aspect was a brief tour of the ethical issues associated with this pharmaceutical, and specifically the examination of a normative question — while we could use this drug to immediately address a serious problem, even if they were perfectly safe and effective, should we do so, or does this pharmaceutical fix to a human-induced problem deprive us of maintaining and cultivating important societal values and personal virtues?

The book would be worth a read for the GP who is interested in semaglutide beyond its position in clinical guidelines, and for GPs who are looking for a book to recommend to their patients on this matter.

Featured book: Johann Hari, Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight Loss Drugs, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024, PB, 336pp, £19.26, 978-1526670144

References

1. Rackham A. Weight loss drug semaglutide approved for NHS use. BBC News 2023; 8 Mar: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-64874243 (accessed 22 May 2024).

2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. BNF: semaglutide. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/semaglutide (accessed 22 May 2024).

3. Khan N. How to ‘drug’ our way out of the obesity crisis (or not): the roll-out of semaglutide. Br J Gen Pract 2024; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp24X737241.

Featured photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash.