Maryam Naeem is a salaried GP at Tulasi Medical Centre, Essex.

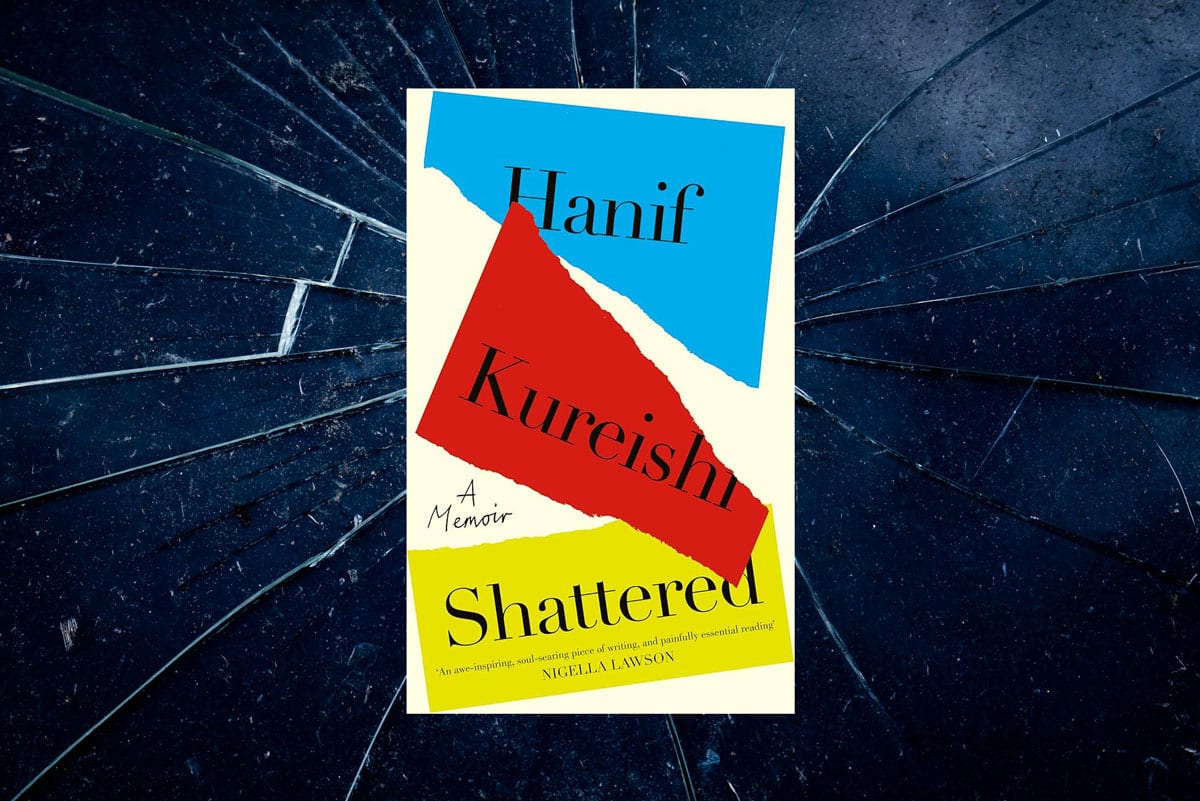

On Boxing Day in 2022 the writer Hanif Kureishi’s life shattered; one minute he was sitting in his partner Isabella’s Roman apartment, sipping a beer, watching Mo Salah score against Aston Villa, and the next he was in a pool of his own blood, his neck in a ‘grotesquely twisted position’ with his partner ‘on her knees beside me’.

What follows is no ordinary memoir, for memoirs are by definition retrospective narrative accounts; what follows here is the contemporaneous compilation of Kureishi’s experience of the seconds, minutes, hours, days, and 12 months following the accident that rendered him tetraplegic; the hyperextension of his neck resulting in a spinal cord injury from C3 to C5.

Unable to hold a pen let alone write, the writer within him nonetheless found a way to communicate to his readers and the wider world what had happened to him and what he was feeling and doing in response. Painstakingly dictated to his partner and son from his hospital bed, the accounts have an urgency, vitality, and viscerality that run through them due to the real-time writing of the accounts; ‘I am determined to keep writing, it has never mattered to me more.’

Shattered is divided into chronological chapters starting with The Fall and detailing, in order, the hospitals in which Kureishi was admitted from Rome to London, before his eventual return home to West London a year later; the first account was written on 6 January 2023 and the final on 26 December 2023 — a year to the day his life changed irrevocably.

“… Kureishi’s ‘Kureishiness’ is not just still intact but alive and screaming … he is still quintessentially himself.”

While naturally much of the book explores change — how one catastrophic moment changes us, changes our ability to function in the world, changes the daily order of our lives, changes our perceptions of ourselves, changes others’ perception of us — much of the pleasure and quiet joy of this book for me was to see how Kureishi’s ‘Kureishiness’ is not just still intact but alive and screaming — that is, that he is still quintessentially himself.

As an avid reader of both his fiction and non-fiction for most of my adult life it was not just reassuring but heartening to see that he is still his usual ascerbic, funny, irreverent, and controversial self; his sense of humour sings through the anguish — ‘Since I have become a vegetable I have never been so busy’ and ‘I am now more intimate with the Heimlich manoeuvre than I am with cunnilingus’.

Readers not familiar with Kureishi may be shocked to discover that cunnilingus, masturbation, and threesomes feature in this memoir of life as a rehabilitating tetraplegic but for readers familiar with the man who once pronounced that ‘there are some fucks for which a person would have their partner and children drown in a freezing sea’ it comes as less of a shock and more of an affirmation that despite horrific assaults on the body we can still retain a sense of who we are and who we have always been.

Who and what we are, how we identify ourselves, and how others identify us has been central to Kureishi’s work from the beginning and no less here; indeed his accident sharply focuses his sense of self: ‘Paki, writer, cripple: who am I now?’ In Italy he acknowledges how he is treated with ‘respect and courtesy’ by everyone and yet ‘there is something tragic, if not disconcerting, to see how closed off it is when it comes to race. Every day I wonder where my brothers and sisters of colour are’.

Once back home in London he observes the opposite situation, ‘Here, the only white faces I see are those of Isabella and my friends. The accents are multifarious … Africans, Afro-Caribbeans, Thais, Filipinos, Irish, Poles … the only person who speaks standard, middle-class English is me.’ Kureishi has spoken at length at the overt racism he was subjected to growing up in the 50s in the suburbs of Kent, and in Shattered we see him wrestling with now being subjected to ableism: ‘It was my first time travelling as a disabled person … I had to wait for the entire plane to disembark … many of the passengers shoved me as they passed, looking down at me pityingly.’

“It is a humbling, funny, graphic, lewd, and humane account of the enduring will to live and to thrive.”

Kureishi reflects that ‘… those in the outside world are appalled by, if not afraid of, those with disabilities’ and how society willingly turns a blind eye to the existence of disabled people: ‘We want to believe we live in a world of healthy and well functioning people, having convinced ourselves that there is a standard of the effective human being. This is a deception, a misleading ideology. It means we cannot always see the disabled, just as in other circumstances we fail to see those of colour, or queers.’

Shattered made me reflect on my own identity as a doctor and more specifically as a GP. I was surprised that Kureishi felt that ‘some of the doctors enjoy bringing bad news’ before I reflected that actually, when we deal with uncertainty and non-clinical issues all day every day, a consultation where we are potentially breaking bad news can sometimes subversively feel less challenging and therefore ‘easier’. While Kureishi speaks affectionately of many of the healthcare professionals who have been involved in his care since the accident, and indeed he lists many doctors and clinical teams in the acknowledgements at the end of the book, Kureishi’s sharp criticism of some doctors is evidenced with the disdain with which he speaks of a psychiatrist: ‘A psychiatrist, visiting me here, said rather sarcastically “Psychoanalysts understand nothing about drugs.” I’m sure there are many psychoanalysts who would say that psychiatrists know little about minds.’

Kureishi tells us early on in Shattered that ‘The word “vocation” comes from the Latin vocatio “a call, summons”‘. I was surprised to feel an overwhelming sadness that I no longer view general practice as a vocation where once I did; years of austerity cuts, secondary care work transferring to primary care without agreement, training, or funding; and rising demand and expectation coupled with diminishing time, resources, and services, all leading to the erosion of the concept of vocation for many I’m sure.

But then, less commonly these days but it still occurs, I will have a consultation where within seconds a rapport is established, an understanding is forged, and something very personal and perhaps previously unsaid is disclosed, and I am reminded that there is still a magic that can occur in a consultation. Kureishi states ‘Work liberates us. We are making a contribution to the world; our art is for others and not for ourselves alone; a connection is being made. This is the spark of life, a kind of love.’

Shattered is an account of the consequences of a catastrophic event in the life of an extraordinary writer and man; the harrowing journey he has embarked on and continues to make. It is a humbling, funny, graphic, lewd, and humane account of the enduring will to live and to thrive.

Featured photo by Katelyn Greer on Unsplash.

A brilliant review of a brilliant book. Thank you Maryam

Thank you Dave