Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Everyone loves a good story. Stories entertain us, but on a deeper level, they also help us make sense of our experience; they are cultural vectors, transmitting the values and wisdom of one generation to the next. The proper use of power is a common theme in traditional tales: secret knowledge, wealth or authority can all be forces for good, but they are tools to be held lightly and applied with care in case of unintended consequences.

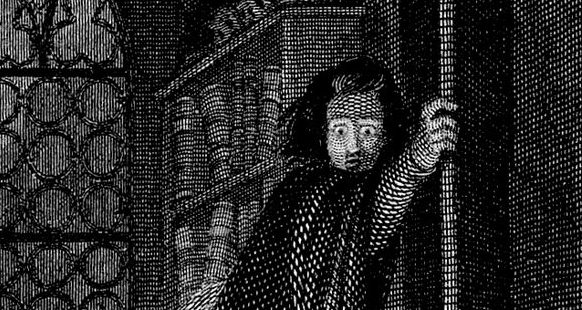

The sorcerer’s apprentice popularised by Disney uses magic to do the cleaning, but ends up making a mess because he lacks his master’s authority over the spirits he has summoned.1 In the tale of the Golem, a rabbi animates a clay figure by inscribing on its head the name of God, but loses control of it after presuming to use its strength for profane ends.2 Mary Shelley’s obsessive scientist Victor Frankenstein builds an artificial human without first considering how to meet its human needs: the creature only becomes a monster because of Frankenstein’s monstrous neglect.3

Restraint in the use of power does not come easily to us in more mundane situations either. Madeleine Albright, United States Secretary of State from 1997-2001, reportedly asked: “What’s the point of having this superb military… if we can’t use it?”4 An armed force deployed to project power must use that power to some purpose, even one to which it is ill-suited, and its mission easily creeps.5 We see something similar in the story of modern medicine.

The sorcerer’s apprentice popularised by Disney uses magic to do the cleaning, but ends up making a mess because he lacks his master’s authority over the spirits he has summoned.

Historically, medicine has provided a framework within which people who are sick can understand what is happening to them, know how to respond, and receive care from others. Doctors have generally lacked the means to influence the outcome of an illness, but through their presence at the bedside and the comforting structure of a regime of treatment, they have perhaps made it a little easier for everyone to await events. Our focus has been less on fighting disease and more on helping people bear it.

This has changed radically within the last few hundred years, with the flourishing of biomedical science and the development of safe surgical treatment, effective drugs, and laboratory and radiological investigations that expose to us the workings of the living body as never before. We have collectively become so powerful that it is becoming difficult to accept that there are limits to what we can know or do. When someone is unwell, we expect to be able to diagnose and treat them promptly, and it no longer feels simply unfortunate when we cannot, but somehow wrong, an affront to our mastery over disease. Biomedicine has become such an accepted paradigm that against a background of cultural ambivalence towards political or religious authority, it is now our default model for understanding problems that have consequences for health, like obesity or gang violence, even though they are not themselves diseases.6,7 In fact, we now concern ourselves largely with people who are not unwell in the usual sense at all, managing risk factors to prevent disease or identifying and treating it at the earliest possible stage. On one level this makes good sense, and we accept unquestioningly the idea that prevention is better than cure. On another, however, it represents a significant development in our story.

If medicine was previously framed interpersonally and socially, and geared towards the successful negotiation of ill health, we see it now more as a quest to eliminate disease through the application of scientific power. The benefits of this quest include our ability to treat conditions which not long ago would have been fatal. However, the unintended consequences are widespread health-related anxiety and a paradoxical growth in the number of those who consider themselves unwell. We have become so preoccupied with our struggle against disease that we are in danger of neglecting these people, whom we have persuaded to become patients without enabling them to bear it well.8

If there is wisdom to be gained from stories, it is surely that we should take care not to let our power for good corrupt our good intentions. Medicine was, and always should be, primarily about looking after people, not just fixing parts of them. Rather than pursuing ever more power over disease, we should perhaps aim to use the power we already have to help people live their lives well.9 It is after all the apprentice in the tale who looses the spirits, but the master who reins them in.

References

- Der Zauberlehrling, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1797

- The Golem, Isaac Bashevis Singer, André Deutsch, 1982

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, Mary Shelley, 1818

- My American Journey, Colin Powell with Jospeh E Persico, Ballantine, 2003

- The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, Rupert Smith, Penguin, 2006

- Preventing serious violence: summary – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) [Accessed 28/6/24]

- Derick T Wade, Peter W Halligan, Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ 2004;329:1398–401

- Marshall Marinker, Why make people patients? Journal of Medical Ethics, 1975, 1, 81-84

- Kleinman A, Catastrophe and caregiving: the failure of medicine as an art, 2008; 371: 22-23

Featured image: Victor Frankenstein observing the first stirrings of his creature. Engraving by W. Chevalier after Th. von Holst, 1831. Source:Wellcome Collection.