Michael Naughton is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) In-Practice Fellow at the Clinical Effectiveness Group, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Queen Mary University of London, London.

Thomas Round is an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow at the School of Life Course and Population Sciences, King’s College London, London.

Rupert Payne is Professor of Primary Care and Clinical Pharmacology at the Department of Primary Care, University of Exeter, Exeter.

Health care is responsible for approximately 5% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, with primary care responsible for over 20% of these emissions.1 The World Health Organization has recognised climate change as the biggest health threat facing humanity and estimates that preventable environmental-related deaths are currently responsible for a fifth of global mortality.2 Reducing the carbon footprint of primary care has the potential to improve the health of our patients and communities, while decreasing workload and saving resources.3

Practical steps to reduce primary care’s carbon footprint

GP practices should take steps to empower patients to look after their health, and self-manage minor and self- limiting conditions; deliver a lean service, without unnecessary testing, referral, or treatments; offer low- carbon alternatives to usual treatment; and prevent ill health to reduce the demand for care from the health system.4

Medications and inhalers

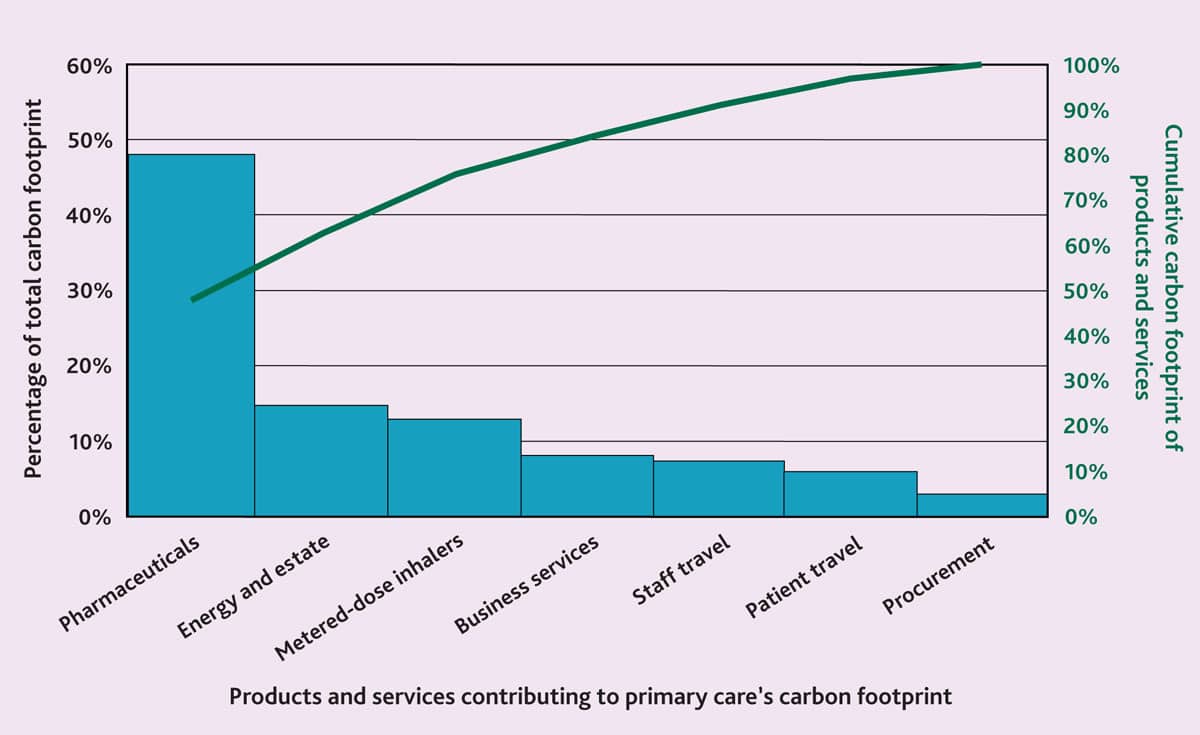

The medications we prescribe account for the majority of the carbon footprint of primary care (Figure 1). Most of this is due to the manufacturing of the medicines.

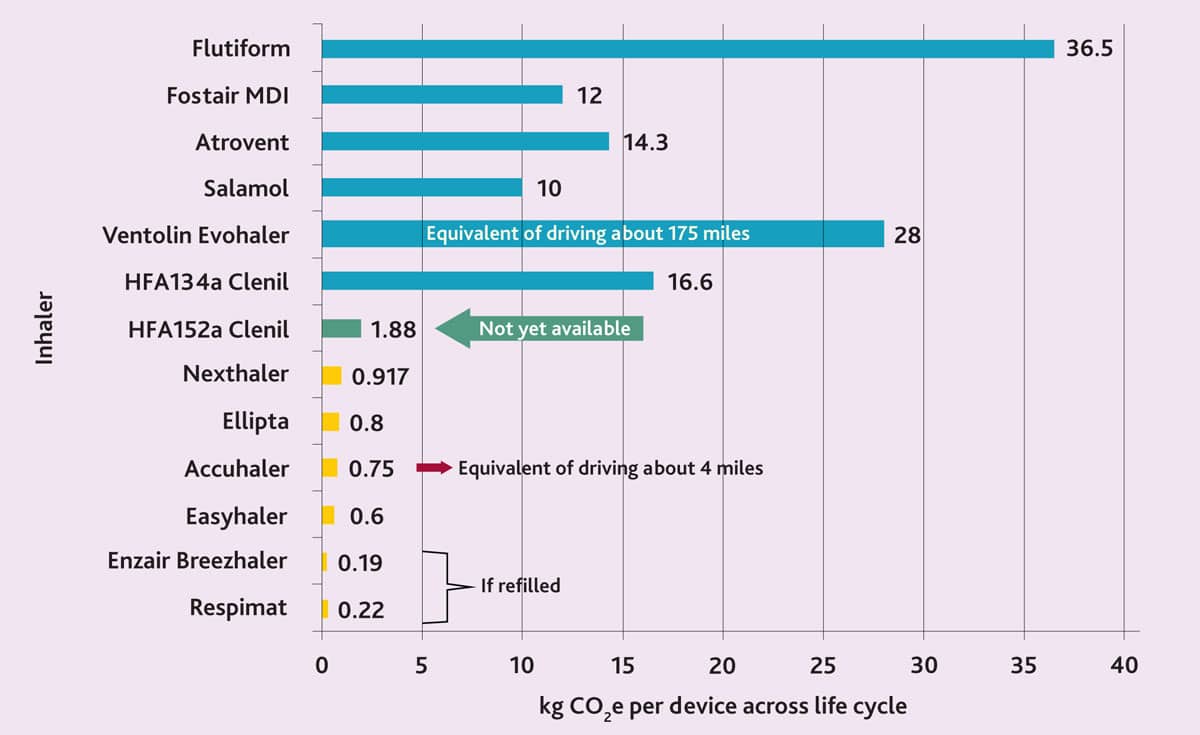

Metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) alone account for 22% of the primary care carbon footprint.6 This is due to the propellants they contain being potent greenhouse gases. Switching to dry powder inhalers (DPIs) can cut the carbon footprint of an inhaler by up to 98% (Figure 2). Up to a third of the emissions from inhalers is in the post-usage phase, mostly due to the leakage of propellants.7 Within primary care, prescribing DPI as first line, with the exception of young children and those with poor inspiratory effort, and pro- actively offering patients already on MDI to switch to DPI at their medication reviews can make a big impact. Encouraging patients to return their inhaler to the pharmacy if not used and after use, so that they can be recycled, also significantly reduces the release of green- house gases from post- usage leakage of propellant gases.

Medication swapping, alternatives to prescribing, deprescribing, and not prescribing

Adherence to long-term prescribed medications is estimated to be 50%,8 and at least 10% of medications prescribed and dispensed in primary care are potentially ineffective or inappropriate.9 Prescribing for self- limiting conditions or where non- drug self-care is appropriate should ideally be avoided (for example, coughs, colds, nasal congestion, and conjunctivitis).10 Educational interventions, such as DIY health, can empower patients to self- manage minor conditions, and reduce attendance and medication usage.

Medicines designated low value by NHS England should ideally not be prescribed.11 Best practice suggests that medicines should be deprescribed if no longer effective, if the benefit is uncertain, or if they’re no longer being taken. Where appropriate, prevention and non-pharmaceutical treatments should be prioritised, for example, psychology, diet and lifestyle interventions, and social prescribing. The greater use of pharmacists in primary care has improved patient safety and reduced costs;12,13 with their skill set and ability to undertake structured medication reviews, they potentially offer an opportunity for medicines optimisation to reduce our carbon footprint.

The Medicine Carbon Footprint Formulary allows a clinician to compare the carbon footprint of the medication they prescribe to alternative drugs.14 This should be used to allow high- carbon medications to be switched to low-carbon alternatives. Natural non- pharmaceutical remedies with evidence of efficacy and a lower carbon footprint could be encouraged, such as turmeric for arthritis pain instead of non- steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs.15

“Primary care physicians and nurses are more trusted than government agencies and public health professionals.”

Consultation and travel to surgery

Remote consultations, such as via telephone and online tools, reduce the carbon footprint associated with patients travelling to the surgery.16 If staff roles allow them to work remotely and it is appropriate then this could be facilitated.

Where travel to a surgery site is necessary, encourage and incentivise staff and patients to choose active (such as walking or cycling) or public transport. Driving a private vehicle should be the last option.

Reducing overinvestigation, overtreatment, waste, and recycling

All clinical activity has an environmental impact so reducing overinvestigation, overtreatment, and wastage can help to reduce your carbon footprint. Laboratory tests have increased three-fold since 2000, with a quarter of tests ordered in primary care thought to be unnecessary,17 and up to 25% of medical services provided failed to improve patient health.18 The Royal College of General Practitioners has an overdiagnosis group that can provide ideas and resources to help your practice reduce unnecessary testing, referrals, and overdiagnosis.19

Using reusable rather than single- use medical equipment decreases the carbon footprint of practice as usually the majority of carbon is released in the production phase of clinical equipment’s life cycle.20

Prevention and management of long- term conditions

Management in primary care is significantly less carbon intensive than in secondary care.1 Prevention of ill health leads to decreased need for care and admission to hospital, minimising the carbon footprint associated with medical treatment.

Sustainability in Quality Improvement gives guidance and suggestions to practices looking to improve the quality of their clinical care and reduce their environmental impact in the process (https://www.susqi.org).

“We can all raise awareness that climate change is a health issue, leading to excess mortality and damaging patients long-term health.”

Advocacy dialogue and raising awareness

Doctors and nurses hold a privileged place in society as one of the most trusted professions. Primary care physicians and nurses are more trusted than government agencies and public health professionals.21,22 We can all raise awareness that climate change is a health issue, leading to excess mortality and damaging patients long-term health. As well as advocating for policies that reduce carbon emissions and create health benefits; this can be done through conversations with members of the public, the media, colleagues, and patients.

What can partners and local primary care leaders do?

Calculating your impact and acknowledging the issue

Calculating the carbon footprint of your organisation (https://www.gpcarbon.org) allows a baseline to be established to inform action and measure progress (although this only includes non- clinical carbon footprint). Declaring and recognising the climate emergency as a health emergency (https://healthdeclares.org) raises awareness and makes addressing the issue an organisational priority.

Practice premises

If possible, the energy generated for your practice building should ideally be locally sourced and from renewable sources (by, for example, installing roof- top solar panels on your practice).23,24 This could include switching to a exclusively renewable energy tariff from a renewable energy supplier.25 The energy efficiency of your practice can be maximised to lower the energy needed to run and heat your building. Minimising energy consumption and wastage can also help (for example, climate control in a building to prevent overheating, and time switches to switch off lights and appliances when not in use).

Make the most of your green spaces by planting trees and plants. As well as absorbing and storing carbon dioxide, it has the added benefit of having green space around the practice that can be accessed by staff and patients, with associated mental health benefits. NHS Forest will provide trees free of charge (https://nhsforest.org/green-your-site).

“Calculating the carbon footprint of your organisation allows a baseline to be established to inform action and measure progress.”

Banking

GP partnerships could consider switching to a bank with an ethical and environmentally friendly ethos (such as Triodos, The Co-operative Bank, or Nationwide Building Society). This means that any money held with the bank will be used for climate-focused investments and avoid investment in the fossil fuel industry.

Conclusion

Climate change will continue to adversely affect our patients’ and wider society’s health. This includes directly through increased deaths due to heat-related illness, increased respiratory illness and exacerbations, increased stroke and cardiovascular events, and an increased burden on mental health. It additionally impacts health indirectly through effects such as displacement of individuals, damage to homes and infrastructure, shortages of food, and increasing costs of food and essentials. Clinical practice and health policy has an important opportunity to make changes to minimise this harm, and to improve the health of patients as a result. We all have a potential role to play in reducing these harms.

Primary care can minimise its contribution to climate change by reducing prescribing, prescribing low-carbon medications, facilitating active travel or remote working and consultations, reducing overtreatment and overinvestigation, optimising long-term condition management, and advocating and raising public awareness. See the version of this article on BJGP Life for a list of further resources.

Competing interest

Thomas Round is an Associate Editor at the BJGP.

Funding

Michael Naughton is funded by the NIHR as part of an In-Practice Fellowship.

References

1. Tennison I, Roschnik S, Ashby B, et al. Health care’s response to climate change: a carbon footprint assessment of the NHS in England. Lancet Planet Health 2021; 5(2): e84–e92.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Climate action: fast facts. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/climate-change/fast-facts-on-climate-and-health.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

3. British Medical Association. Sustainable and environmentally friendly general practice: GPC England policy document. 2020. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2570/bma-sustainable-and-environmentally-friendly-general-practice-report-june-2020.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

4. Mortimer F. The sustainable physician. Clin Med (Lond) 2010; 10(2): 110–111.

5. South East London Integrated Care System. South East London Green Plan 2022–2025: our Plan for a sustainable integrated care system. 2022. https://www.selondonics.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ICS-Green-Plan-2022-2025.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

6. Faculty of Public Health Special Interest Group — Sustainable Development. The NHS: carbon footprint. https://www.fph.org.uk/media/3126/k9-fph-sig-nhs-carbon-footprint-final.pdf (accessed 28 Nov 2024).

7. Janson C, Henderson R, Löfdahl M, et al. Carbon footprint impact of the choice of inhalers for asthma and COPD. Thorax 2020; 75(1): 82–84.

8. WHO. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

9. Department of Health and Social Care. Good for you, good for us, good for everybody. A plan to reduce overprescribing to make patient care better and safer, support the NHS, and reduce carbon emissions. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1019475/good-for-you-good-for-us-good-for-everybody.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

10. NHS England. Policy guidance: conditions for which over the counter items should not be routinely prescribed in primary care. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/policy-guidance-conditions-for-which-over-the-counter-items-should-not-be-routinely-prescribed-in-primary-care (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

11. NHS England. Items which should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: policy guidance. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/items-which-should-not-routinely-be-prescribed-in-primary-care-policy-guidance (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

12. Mann C, Anderson C, Avery AJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists in general practice: pilot scheme. Independent evaluation report: executive summary. 2018. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/pharmacy/documents/generalpracticeyearfwdrev/clinical-pharmacists-in-general-practice-pilot-scheme-exec-summary.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

13. Hayhoe B, Cespedes JA, Foley K, et al. Impact of integrating pharmacists into primary care teams on health systems indicators: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X705461.

14. Taylor H, Mahamdallie S, Sawyer M, Rahman N. MCF classifier: estimating, standardizing, and stratifying medicine carbon footprints, at scale. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2024; 90(11): 2713–2723.

15. Paultre K, Cade W, Hernandez D, et al. Therapeutic effects of turmeric or curcumin extract on pain and function for individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2021; 7(1): e000935.

16. Curtis A, Parwaiz H, Winkworth C, et al. Remote clinics during coronavirus disease 2019: lessons for a sustainable future. Cureus 2021; 13(3): e14114.

17. Watson J, Burrell A, Duncan P, et al. Exploration of reasons for primary care testing (the Why Test study): a UK-wide audit using the Primary care Academic CollaboraTive. Br J Gen Pract 2024; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp.2023.0191.

18. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA 2019; 322(15): 1501–1509.

19. Royal College of General Practitioners. Overdiagnosis group. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/about/communities-groups/overdiagnosis (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

20. Keil M, Viere T, Helms K, Rogowski W. The impact of switching from single-use to reusable healthcare products: a transparency checklist and systematic review of life-cycle assessments. Eur J Public Health 2023; 33(1): 56–63.

21. Maibach EW, Kreslake JM, Roser-Renouf C, et al. Do Americans understand that global warming is harmful to human health? Evidence from a national survey. Ann Glob Health 2015; 81(3): 396–409.

22. Ipsos. Ipsos UK Veracity Index 2024. 2024. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2024-11/Veracity%20index%202024_v1_.pdf (accessed 28 Nov 2024).

23. Faia R, Soares J, Pinto T, et al. Optimal model for local energy community scheduling considering peer to peer electricity transactions. IEEE Access 2021; 9: 12420–12430.

24. Liu J, Yang H, Zhou Y. Peer-to-peer energy trading of net-zero energy communities with renewable energy systems integrating hydrogen vehicle storage. Applied Energy 2021; 298: 117206.

25. Energy Saving Trust. Energy at home: how to switch energy supplier. 2024. https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/advice/switching-your-energy-supplier (accessed 22 Nov 2024).

Featured photo by Egor Myznik on Unsplash.

Great article thank you. However, you have omitted to mention the positive impact we can make for health and climate through dietary change. Shifting away from animal based meals to meals centered around healthy plant-based foods will not only improve health outcomes but drastically reduce the environmental impact of our diet. Without food system transition we will not meet our climate and nature targets even if we ended fossil fuel use today. So in our trusted position as health professionals we need to support patients and colleagues to adopt healthy and sustainable diets. Role modeling with the GP practice environment could go a long way.