Rupal Shah, Anita Berlin, Rofique Ali, Jenny Blythe, Clare Etherington, Kavita Gaur, Lucy Langford, Anna Moore, Louise Younie, Jeeves Wijesuriya, Sabir Zaman, and Liliana Risi are a group of healthcare practitioners and educators in London with a particular interest in health equity.

The COVID-19 syndemic triggered a period of immense disruption in healthcare structures, practices, education, and communication.1 It exposed clinicians to unprecedented stress and laid bare local and global inequalities in health outcomes, for which we were ill prepared. These phenomena were exaggerated by the tendency for health professionals to work and learn in silos: specialist versus generalist; undergraduate versus postgraduate; physicians versus allied health professions; with a disjoint between health care, social care, and the voluntary sector.

We wish to share the story of an innovative digital intervention that has helped to overcome existing divisions by creating a vibrant interdisciplinary network of learning and health activism. We describe how a few family physicians created a virtual community on WhatsApp to share information and offer solidarity: the London Deep End Health Equity community.

Our group has evolved organically since its inception in September 2020, but we have remained true to our original purpose of trying to reduce the impact of longstanding health inequity, racism, and social exclusion, to address climate change and to promote fairer systems and healthier places to live and work.

The chaos and destruction caused by COVID-19 highlighted pre-existing health and social inequalities. We have therefore deliberately used a syndemic lens, which has helped us to see how the impact of a disease (here COVID-19) can be amplified and exacerbated by wider pre-existing determinants of health.2

Surviving beyond the pandemic, the community now has over 200 members transcending traditional professional silos to include family physicians, secondary care doctors, and allied health professionals; undergraduate and postgraduate learners and teachers; and social, community, and voluntary sector activists.

In addition to posting ideas and information on WhatsApp, the community participates in workshops, hybrid events, and quality improvement initiatives. Members have connected with one another across disciplines to begin or enhance other, related projects, a few of which are described below. Our experience of being members of the Deep End community supports the premise that urgent, complex global and local health challenges require health professionals to work collaboratively, across disciplines and sectors, using a distributed leadership model.3

We describe here our approach and activities, and discuss limitations.

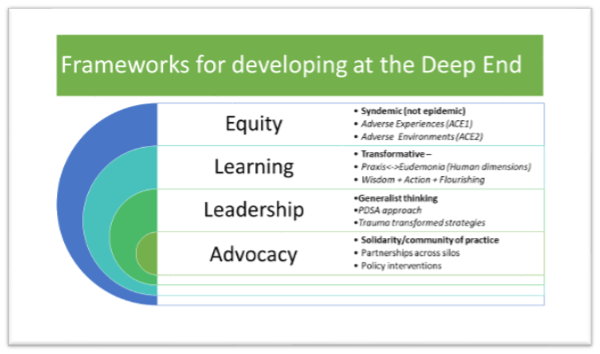

Organising principles: Deep End and the inverse care law

The original Deep End movement was established in Scotland in 2009, when a group of family physicians convened a conference to explore how they could work together to address the issues they and their patients faced. Acting on a desire to address the inverse care law4 and the overlapping impact of adverse childhood experiences and adverse community environments, referred to as the ‘pair of ACEs’,5 these clinicians established the ‘Deep End project’6 based on four iterative principles: support, learning, improvement, and advocacy. They showed that this approach improved workforce resilience, deepened connections with community services, and addressed learning needs relating to deprivation-specific problems in primary care.7,8 Deep End groups have subsequently been created by family physicians in cities across the world. Our London group is one such and follows the Deep End principles outlined above.

Inspiration was drawn from a pre-existing Deep End workshop series established in North West London in 2018 prior to the onset of COVID-19. The workshops are ongoing and have provided a robust evidence base, peer support, and the opportunity for critical reflection and action to increase health equity and advocacy (Figure 1).

The Deep End Fellowships established in association with the workshops laid the groundwork for the subsequent creation of other Health Equity Fellowships, which are detailed below. The London Deep End logo evolved from initial work done in North West London.

Membership — who and how

The group started off with just a few family physicians who included representatives from key local services, as well as undergraduate and postgraduate educational institutes. These founder members invited others in. Word of mouth and attendance of workshops also drew people in, so that membership of the WhatsApp group now stands at 218 (September 2023).

Attention is given to how people are incorporated into the group. This takes the form of a ‘micro-chat’: a short conversation to increase trust through maximising inclusion and belonging, and exploring shared values.9 The micro-chat is based on the premise that the culture of a group is created through the nature of the interactions people have with one another.10

The values of social justice, solidarity, and advocacy are fundamental to our group. Posts that are derogatory in nature and vilify a particular person or political party without serving the purpose of encouraging positive change negatively impact the spirit and values of the group; such posts are therefore actively discouraged.

Initially, membership permissions were managed by one person. However, once the process was established, all members became ‘administrators’ of the group and are able to bring in others with diverse interests and backgrounds who share similar values; this permissive architecture is founded on trust within the group and is based on the principle of distributed leadership.3

Membership has expanded from family physicians to other members of the primary care team (for example, social prescribers, pharmacists, and nurses) and to community and voluntary organisations. We have actively encouraged young practitioners and medical students to join. Hospital clinicians with an interest in the wider determinants of health are part of the group, along with public health consultants, medical directors, and service commissioners. The location of members has extended from East London, where the group started, to now include the whole city.

London Deep End Health Equity Group — activities

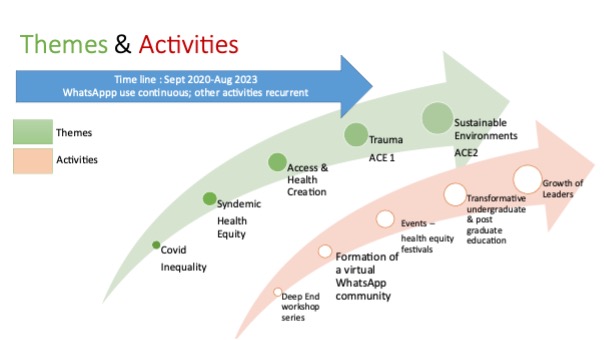

- WhatsApp posts — data and summary of themes/threads. Over 37 months (September 2020–September 2023), on average, there have been 64 links posted to events, courses, and journal articles per month (range 4–123; total 2392), as well as an average of 7 documents posted per month, mostly academic articles (range 1–26; total 267). Over the 3 years prior to and including August 2023, three-quarters of members have regularly read posts. Many of the posts are about sharing ideas, initiatives, and making connections, collaborating about local services and concerns. Over time, themes have emerged (see Figure 2), with members building on other posts, sharing activities, and adding blue-sky thinking. New members often inject new perspectives — for example, when social prescribing link workers, trainees, and colleagues from specialist services and new geographical areas become members. The energy generated by transdisciplinary interactions shows the power of breaking down epistemic and power barriers.

- Festivals and conference. There have been six virtual or hybrid Health Equity Festivals11,12 to encourage dialogue, and develop commitment and shared understanding. The festivals have adopted creative, arts-based approaches to support flourishing and foster trust, wellbeing, and shared understanding. Each festival has culminated with actions for moving forward, captured in word clouds to inform the planning actions for the next cycle. This is in line with the Glasgow Deep End group — we in the London group have also applied the quality improvement framework described by Ham et al.13 Plan/do/study/act (PDSA) cycles have formed the basis for creatively generating and capturing change ideas to harness commitment and advocacy.

- Related initiatives. Members of the Deep End group have drawn inspiration from one another and have collaborated on other, related projects. Many of these were already in existence before the group was set up, but have been enhanced by the connections formed through membership. There are numerous such initiatives, too many to list here, but some examples are given below:

- Transformative community-based undergraduate medical education modules created at Queen Mary University of London and Imperial College London:

- community diagnosis14 modules for all medical students and year 4 health equity modules;

- student selected module: Deep End and creative enquiry;15 and

- students as vaccinators: service-learning partnerships.

- Transformative community-based undergraduate medical education modules created at Queen Mary University of London and Imperial College London:

-

- The London Thinking Together programme, which is part of the Enhancing Generalist Skills programme,16 is aimed at postgraduate doctors and other clinicians from multi-professional backgrounds. The programme covers the six domains of generalism (population health, social justice, person-centred care, sustainability, systems working, and complex multimorbidity). The Education Lead, Rupal Shah, has worked on the programme with members of the Deep End Group, particularly with people from disciplines and professions that would not usually be represented within postgraduate education programmes. Part of the programme involves trainees undertaking quality improvement projects within one of the six domains of generalism, many of which have been supported by members of the Deep End group.

- Inter-sectoral advocacy. In February 2020, 7 months before the Deep End group was formed, an allied group — the London Greener Practice — was facilitated by one of the founding members of the Deep End group (Liliana Risi), with physicians awarded scholarships in leadership in climate health creation, funded through inter-sector collaboration between NHS institutions and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Essentially, these groups share the same vision and there is an overlap in membership of about 40%.

- Hospitals without Walls. One member of the group, Martin Griffiths, a trauma surgeon in a London teaching hospital, has introduced an initiative whereby victims of trauma (particularly gang-related violence) are supported on discharge and for several months or years afterwards by case workers, thus reducing readmission rates. His story has been captured in two podcasts,17 which were funded through the Enhancing Generalist Skills programme.

- Health Equity Fellowships. Health Equity Physician fellowships were trialled in East London from October 2020 and funded through the North East London Integrated Care System. These East London Fellowships were modelled on the successful pre-existing West London Deep End Fellowship work started in early 2019 and funded one half-day per week of physician time to attend the Deep End workshops and undertake supported quality improvement work.

- Subgroups. There now exist several splinter groups, whose members discovered particular commonalities. These include: the Flourishing group, the Story Garden, the Trainee group, and the Deep End book club, who meet intermittently, usually virtually. The smaller size of these groups allows members to form close networks of relationships.

Limitations

As we have described above, there is a high volume of traffic in the WhatsApp virtual space. The thread of posts is uncurated and could be perceived as overwhelming, especially for people who are time poor. The search function on WhatsApp is limited, making it hard to retrieve documents and links previously posted. However, we now have our own webpage, which will help to address these problems (https://www.fairhealth.org.uk/deep-end-london).

The success of the group has led to an expansion in numbers, with most members no longer enjoying personal relationships with most others in the group. This risks anonymity. The large size of the group may also act as a deterrent to less confident members feeling able to post, although there is a smaller trainee subgroup, as well as other smaller splinter groups. Inclusion might be improved by adopting a mechanism that enables people to post anonymously.

It is also challenging to capture lived experience of members of the group or to be clear of other members’ spheres of influence. One member, Rofique Ali, has set up a members’ Padlet to address some of these issues.

Finally, it is difficult to evidence the extent to which membership of the group directly influences change initiatives.

Conclusion

We describe an informal community of practice based on the four Deep End principles of support, learning, improvement, and advocacy, located in a virtual space but linked to geographies across London that aims to address the inverse care law. Members have reported that belonging to such a community ‘restores hope’, affording them opportunities for connection and of effecting meaningful change, in accordance with their values. It therefore at least partially achieves the initial aims at the group’s inception of attending to the loneliness, isolation, and moral distress of working in areas of deprivation; and to demonstrate through evidence, how the approach of the Scottish Deep End project can change the experience and outcomes for those living and working in the ‘deep end’ of London. The group is now a large, vibrant, self-directed community, with multiple offshoot groups. The WhatsApp group enables learning and borrowing from each other’s experiences of what works and what doesn’t, but much of the grassroots project work is rooted in its own place. The primacy of neighbourhood, or being specialists in place, is critical. It is this openness to local knowledge that feeds continuity and trust in our communities.

Our story is of particular relevance to healthcare leaders who are aiming to improve workforce retention in health care and address the Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) agenda. The power of connections and networks of people with aligned values and the link with transformative learning is currently under-utilised. Belonging to the group supported positive change. As described above, several members have used the connections they have made for action-oriented health creation. This has the potential to improve population and climate health, but also to combat alienation for individual practitioners by instilling a new sense of agency and purpose.

References

1. Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet 2020; 396(10255): 874.

2. McGowan VJ, Bambra C. COVID-19 mortality and deprivation: pandemic, syndemic, and endemic health inequalities. Lancet Public Health 2022; 7(11): e966–e975.

3. Harris A, Jones M, Ismail N. Distributed leadership: taking a retrospective and contemporary view of the evidence base. School Leadership & Management 2022; 42(5): 438–456.

4. Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971; 297(7696): 4015–4412.

5. Ellis WR, Dietz WH. A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Acad Pediatr 2017; 17(7S): S86–S93.

6. Watt G; Deep End Steering Group. GPs at the deep end. Br J Gen Pract 2011; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X549090.

7. Sturgiss E, Tait PW, Douglas K, et al. GPs at the Deep End: identifying and addressing social disadvantage wherever it lies. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48(11): 811–813.

8. Berwick DM. Developing and testing changes in delivery of care. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128(8): 651–656.

9. Ansell C, Gash A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J Public Adm Res Theory 2007; 18(4): 543–571.

10. Spicer J, Ahluwalia S, Shah R. Moral flux in primary care: the effect of complexity. J Med Ethics 2021; 47(2): 86–89.

11. Bromley by Bow Centre. Restoring hope – Health Equity Festival & Celebration. https://www.bbbc.org.uk/insights/news-and-resources/news-and-resources-health-equity-festival (accessed 31 Jan 2024).

12. Bromley by Bow Centre. London Health Creation Spring Festival: regenerating ourselves, our systems, our world. 2022. https://www.bbbc.org.uk/insights/news-and-resources/health-creation-festival (accessed 31 Jan 2024).

13. Ham C, Berwick D, Dixon J. Improving quality in the English NHS: a strategy for action. 2016. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/ae9501a18c/improving_quality_in_english_nhs_2016.pdf (accessed 31 Jan 2024).

14. Shah D, Blythe J. Using community diagnosis on primary care placements for medical students. Educ Prim Care 2022; 33(2): 109–112.

15. Brown MEL, Younie L. How creative enquiry can help educators develop learners’ person-centredness. Med Educ 2022; 56(6): 599–601.

16. Health Education England. London’s Enhancing General Skills programme. 2023. https://london.hee.nhs.uk/medical-training/london%E2%80%99s-enhancing-generalist-skills-programme (accessed 31 Jan 2024).

17. Shah R, Griffiths M, Keville R. Hospitals without walls – people (video on YouTube). 2023. https://learninghub.nhs.uk/Resource/41425/Item (accessed 31 Jan 2024).

Featured photo by Liliana Risi: Flourishing in the tightest space possible. Sunflowers on an estate in Tower Hamlets.