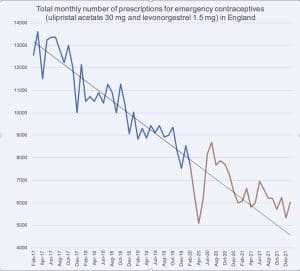

The reclassification of emergency contraception (EC) in England in 2001 allowed EC to be purchased by females aged 16 and over at pharmacies without a doctor’s presentation (consultation with a pharmacist is still required). Since then, the total number of annual prescriptions for EC (ulipristal acetate single-dose 30 mg tablet, and levonorgestrel single-dose 1.5 mg tablet, both of which may be used as EC in the National Health Service [NHS])1 in England has declined substantially (falling by 51% from around 265,000 in 2008 to around 130,000 in 2018),2 while the proportion of EC being accessed without a prescription has dramatically increased.3 Monthly prescribing data for EC in England is available from February 2017 to January 2022 inclusive (at the time of writing) at OpenPrescribing.4

…data suggests the demand for EC in England increased above pre-lockdown and trend-expected levels shortly after social contact restrictions were eased.

The first UK national COVID-19 lockdown commenced in March 2020 and prevented contact between households until measures were incrementally eased from June 2020.5 The total number of EC prescriptions (BNF paragraph search term: “7.3.5”) in England in November 2019, December 2019, January 2020, and February 2022 was 8281, 7544, 8531 and 7705, respectively, and featured as part of the declining trend in monthly numbers of EC prescriptions. This number dropped substantially in March 2020, April 2020 and May 2020 (6339, 5094, 6152, respectively) as social contact was restricted under lockdown conditions, returned to pre-lockdown levels in June 2020 (8191) as restrictions began to ease, increased above pre-lockdown levels in July 2020 (8677) as easing continued, and continued to remain above the extrapolated trendline (from February 2017-February 2020) until the second national lockdown came into effect in November 2020 (see Figure 1).4

Figure 1. Trend line is with respect to data from February 2017 to February 2020 inclusive (blue) and extrapolated across all subsequent data (orange)

Given the shift from prescription-based to over-the-counter EC access over the previous two decades, it is unlikely that this post-lockdown increase in EC prescriptions was offset by a decrease in over-the-counter EC access. Rather, it is likely that a similar increase in EC access was seen over-the-counter, thereby amplifying the effect size.

…the unprotected sexual intercourse or contraception failure leading to such demand has clear implications for the risk of sexually transmitted infections.

This admittedly crude analysis of prescribing data suggests the demand for EC in England increased above pre-lockdown and trend-expected levels shortly after social contact restrictions were eased. In addition to unintended pregnancies (which EC aims to prevent), the unprotected sexual intercourse or contraception failure leading to such demand has clear implications for the risk of sexually transmitted infections. As such, public health messaging regarding safe sexual practices should be enhanced amongst relevant populations as any future social contact restrictions come to an end.

Note: the copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) may also be used for EC in the NHS, but requires a doctor’s prescription, and can also be used for non-emergency contraception. There were no substantial changes in the (relatively low) total monthly number of prescriptions for Cu-IUD in England from February 2017 to January 2022, although the indication (EC or non-emergency contraception) was not available (BNF paragraph search term: “Copper T380 A intrauterine contraceptive device”).

References

- NICE CKS. Contraception – emergency. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/contraception-emergency/management/management/#choice-of-emergency-contraception [accessed 29 March 2022]

- NHS Digital. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services (Contraception), England, 2018/19 [NS]. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/sexual-and-reproductive-health-services/2018-19/emergency-contraception [accessed 29 March 2022]

- A Glasier, P Baraitser, L McDaid et al. Emergency contraception from the pharmacy 20 years on: a mystery shopper study. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 2021; 47:55-60. DOI: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200648

- OpenPrescribing.net, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, University of Oxford, 2022 [accessed 29 March 2022]

- Institute for Government. Timeline of UK coronavirus lockdowns, March 2020 to March 2021. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf [accessed 29 March 2022]

Featured image by Dima Mukhin on Unsplash