A few years ago I was asked by a colleague to co-author a paper for a prestigious medical journal, to give both the GP and the secondary care perspective on the practicalities of the acute management of the main subtypes of disease X. I started a very happy collaboration with a professor of disease X,* and between us we threw a few ideas around. She knew a thing or two about the pathology and management of disease X and, despite recently leaving clinical medicine, I still remembered a few things about the potential and the limitations of managing patients in the community.

We produced a creditable first draft. Professor X contributed the nuances of diagnosis, in particular the subtypes of disease X and the immediate medical management. I contributed how one would determine whether and how such patients could be safely managed in the community; what resources and expertise would be needed, how to safety net, how communication between the practice, out of hours services and secondary care could be managed. I even produced some algorithms showing the practical considerations on which one would make treatment and acute referral decisions, for example does the practice have a nurse specialist in disease X, the patient’s level of capability and support, is it a Friday afternoon, do you have specialist advice to hand? etc.

But the word count would then be an issue. So perhaps some of the unscientific GP stuff could be cut?

So we sent off the paper.

The peer reviewers decided that we needed more hard science, and the subtleties of the less common disease X variants should be explored. But the word count would then be an issue. So perhaps some of the unscientific GP stuff could be cut?

OK. We do this, but still manage to keep in my nice “what to do” algorithms. After all, the commission was to consider the practicalities, and as any GP knows, biomedicine is usually the easy bit. So we send off the second draft.

Two different peer reviewers ask that we change things around a bit, naturally in a different way from the first peer review. Oh, and we still need more science and a bit less of this woolly stuff about decision making. Less “what to do” algorithms and more hard science. We send off a third draft.

But some further changes are required – this is a big prestigious journal after all. What do we mere authors know? And, yes, out go my algorithms and most all of my remaining content. Professor X is as frustrated as I – even as more and more of the science is pouring into the paper it addresses the original commission less and less.

But is there anything in this other than my trivial peevishness?

But is there anything in this other than my trivial peevishness? Miranda Fricker helpfully talks about epistemic injustice – that the voices, indeed the knowledge structures, of some groups are excluded.1 The problem is similar to the concept of the “medical gaze”, introduced by Foucault who claimed that “A ‘gaze’ is an act of selecting what we consider to be the relevant elements of the total data stream available to our senses. Doctors tend to select out the biomedical bits of the patients’ problems and ignore the rest because it suits us best that way.”2

So as GPs we are being hoisted by our own petard. Just as the biomedical model squeezes the patient’s voice into a corner so we find ourselves, our particular skillsets, our particular knowledge of how the 99% of the world that exists outside of hospital works, being squeezed into a corner by our high profile biomedical narratives.

So what is the answer? I honestly don’t know. But part of the answer must be to recognise epistemic injustice, whether foisted upon patients or upon us, and call it out. In person, in what we say, and, again and again, by making a credible case in what we write. Even if it is “just” in the BJGP.

But still, I have a nice paper with my name on, which still gets cited from time to time. Just don’t come crying to me if you don’t know what to do with your patient on a wet Friday afternoon when their blood results come through.

*Deputy Editor’s note: Evidence of consent from Professor X to have this narrative shared has been provided to the editorial team. See also https://bjgp.org/content/63/611/312 for a discussion of the ‘Medical gaze’

References

- Fricker M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Foucault. Misselbrook D. BJGP 2013; 63 (611): 312. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp13X668249

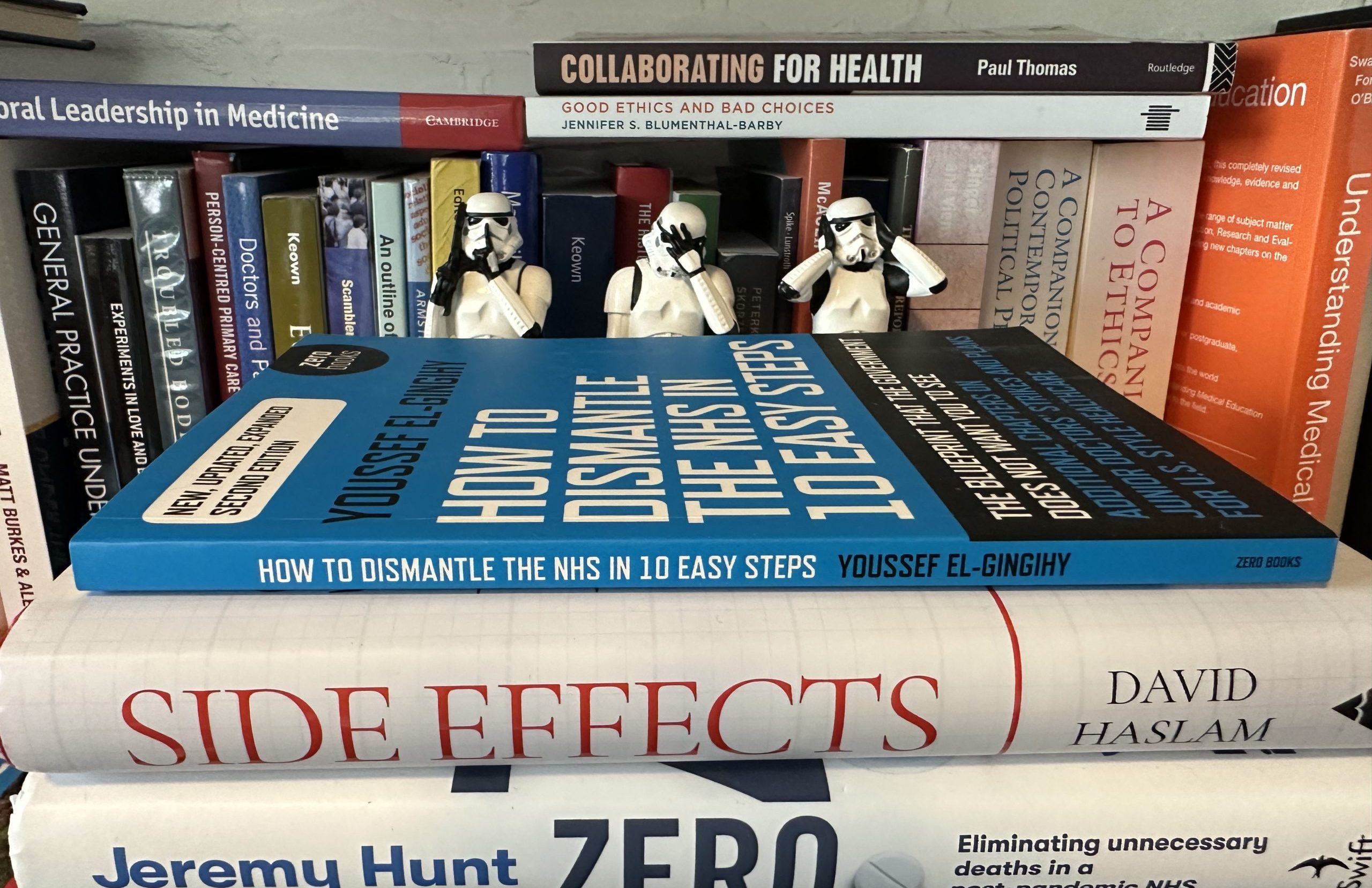

Featured image: The future of general practice 2: hidden workers, by Andrew Papanikitas, 2023