Armando Henrique Norman is a family physician and professor in family and community medicine at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Armando Henrique Norman is a family physician and professor in family and community medicine at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

GPs deal with disease and illness in patients. The former is a biomedical abstract framework that should have a sound physio-pathological and predictive power. The latter is the patient’s inner experience of being ill. The illness experience is of a different order, which GPs have no means to quantify.1

Disease as an abstract entity can be defined as ‘convenient fictions, designed to help predict the behaviour of things in the observable world’.2 Illness as a felt experience is ‘a phenomenal property associated with the degree of clarity or vividness of experience [and the] mind is the sole ground of [its] concreteness.’ 2 This understanding gives primacy to the mind as all experiences appear, are known, and are made by this ‘knowing element’ in us named consciousness.3 However, language has created a division between the body, which can be measured, and the mind, which lacks objective materiality.

Reality outside the mind is an abstraction

As the physicist Andrei Linde explains, ‘our knowledge of the world begins not with matter but with perceptions. I know for sure that my pain exists, my “green” exists, and my “sweet” exists […] everything else is a theory.’ 2

“… human beings have two separate elements, but essentially they are one as there is nothing to an iceberg but water!”

McWhinney and Freeman1 have contended that reality is multilevel and hierarchical, within which higher levels cannot be fully explained by lower levels. Complex theory also recognises that ‘each hierarchical level [layer] of organisation has goals imposed from above, that are free to develop their own autonomous way to achieve them’.4

This acknowledgement implies what Kastrup refers to as epistemic asymmetry,2 that is, phenomenal consciousness cannot be compared to the regularities and patterns of the observable world. The latter constitutes explanatory models or abstractions that vary historically and culturally. The concreteness of the world is inner, and the outer world is an abstraction.

We never leave the mind level, or to use Edmund Husserl’s concept of the life-world: ‘The life-world is the real, experienced, lived in world … a much richer world than that of mere objects, or that defined by the objective existence of things. The life-world gives rise to the scientific world but it is much more than the world described by science as mind is the fundamental substrate of all experience’.1

The iceberg metaphor

According to Schumacher, ‘we do not grasp that we are invisible […] that life, before all other definitions of it, is a drama of the visible and the invisible’.5 The iceberg metaphor is commonly used to illustrate the seen and unseen aspects of human manifestation. The floating top iceberg-part corresponds to human physical manifestation. The beneath-the-sea iceberg-part represents the patient’s veiled world of longings, fears, dreams, ideas, concerns, and expectations, with its deepest part merging into the collective oceanic unconscious.

“Patients should be informed about the distinction between a disease of the body and the consensus-based nature of mental disorders.”

Provisionally, human beings have two separate elements, but essentially they are one as there is nothing to an iceberg but water! The primary experience of patients (the life-world consisting of emotions, perceptions, and conceptions) appears as bodies by secondary experiencers, that is, doctors. Like the ice, the body is a dynamic process of the mind’s localisation, which can be registered by sense perceptions before it melts into the ocean of consciousness.2 Hence, does the iceberg generate the ocean or is it a localisation of the ocean itself? The vastness of consciousness can explain the particular, not the other way around.

Science is counterintuitive

In the past, the earth has been the centre of the universe as the sun, stars, and planets seemed to revolve around us. However, science has demonstrated that the earth is in rotational and translational movement, and the heliocentric model has become dominant. Could the dichotomic construction of mind and body also be an acculturation process? Does the comparison between the inner world (mind) and outer world (matter) constitute a real dichotomy or is it a conditioned error?

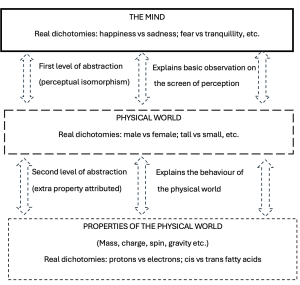

Dichotomic entities should be mutually exclusive as they are, by definition, opposites. According to Kastrup,2 these ‘dichotomies must reside in the same level of abstraction [and] matter outside mind is not an empirical observation but rather an explanatory model’. For instance, birth and death are opposites, but not life and death. Life belongs to a different hierarchical order. Life, consciousness, and self-awareness are modes of the sole ground of experience, that is, phenomenal consciousness.

The first level of abstraction is framed in accordance with sense perceptions (perceptual isomorphism), within which the world’s basic observations are explained. Thus, no surprise that brain activity on image scans shows correspondence to humans’ inner experience. The reality of other beings is framed differently as they (bats, cats, snakes, and insects, for example) are endowed with distinct sensorial equipment. The conundrum stems from forgetting that the material outer world is an explanatory model, and that phenomenal consciousness gives its concreteness. As science digs into the tapestry of ‘outer reality’, the level of abstraction increases as new properties are attributed to the ‘material world’. For instance, we do not have direct access to quantum particles as we have to the warmth of the sun on our skin. Figure 1 illustrates the levels of explanatory abstraction and the corresponding positioning of dichotomies at each step of abstraction.

Implications for clinical practice

The epistemic symmetric principal (ESP) should inform the everyday practice of GPs, especially in mental health. The ESP clarifies Thomas Szasz’ aphorism: if it is a disease, it cannot be mental; and if it is mental, it cannot be a disease.6,7 The mind does not age, die, or get sick. The body, like an iceberg, gradually vanishes, but not the ocean, not consciousness.

Nonetheless, health authorities tend to mistakenly convey that diagnosis in mental health offers an aetiological explanation, instead of highlighting its descriptive nature.8 Mental disorders (that is, out of order) are conventions, consensus-based entities, and not natural facts, as in the case of tuberculosis or diabetes. This misconception also permeates researcher design, within which mental dimension is treated as ‘disease’ in randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with ‘validated scales’ functioning as ‘surrogate biomarkers’ for diagnosing mental disorders.9

“The body does not generate the mind but is a process of self-localisation of the mind itself …”

In evidence-based medicine (EBM), RCTs are the gold standard of best practice. Thus, the evidence-based group-level symptom-reduction model has become dominant in clinical care via best practice guidelines.10 This environment has blurred the epistemic asymmetry between the mind and the body leading to a disease-centred model in mental health. For instance, from 2006–2012 of the Quality and Outcomes Framework era the use of the Primary Health Questionnaire-9 was considered the standard, best practice approach to depression management.

Mental health issues relate to patients’ illness dimension. The approach needed is phenomenological, intersubjective, and constructivist.9 According to Van Os, clinicians should offer ‘an explanatory model, [by] proposing a theory for change, raising expectations, and inspiring patient engagement, all within the context of a productive therapeutic relationship characterised by empathy, an active and caring attitude, and the capacity to motivate, collaborate and facilitate emotional expression.’ 10

Patients should be informed about the distinction between a disease of the body and the consensus-based nature of mental disorders. This distinction allows the balanced use of psychiatric drugs when it is required. In this regard, Joanna Moncrieff’s drug-centred model (Drug-CM) is a useful guidance.11 The Drug-CM entails that:

a) psychiatric drugs affect the normal brain functioning by producing altered states of mind. They are considered toxic agents that might have therapeutic usefulness in some cases;

b) the alcohol paradigm functions as an explanatory mode. Drinking alcoholic beverages might contribute to reduced shyness (social phobia), but it does not imply that the brain lacks ethanol;

c) the emphasis is in the patient’s entire experience with the medication;

d) adherence to psychiatric drugs is optional and relapses function as learning opportunities; and

e) the focus is on patient’s therapeutic objectives.11

Hence, ESP contributes to disentangle the misleading concept that mental health issues are diseases caused by an imbalance in brain chemistry requiring life-long treatment with psychoactive drugs.

Final comments

This article has explored the usefulness of idealism as a valid philosophical principle to guide family physicians in their daily practice. Idealism gives primacy to the mind as the substrate of all experiences. The body does not generate the mind but is a process of self-localisation of the mind itself, as exemplified by the iceberg metaphor. This has been empirically documented in prospective studies of cardiac arrest through the external visual awareness phenomenon, in which patients lucidly observe their own bodies and the health staff during their cardiopulmonary resuscitation settings.12 Explanatory models are imperfects, but idealism and its ESP seems to be a powerful framework to deal with complex cases and uncertainty in primary health care.

References

- McWhinney IR, Freeman T. Textbook of Family Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Kastrup B. Conflating abstraction with empirical observation: the false mind-matter dichotomy. Constructivist Foundations 2018; 13(3): 341–361.

- Spira R. The Nature of Consciousness: Essays on the Unity of Mind and Matter. Oakland, CA: Sahaja Publications and New Harbinger Publications, 2017.

- Neighbour R. The Inner Physician: Why and How to Practise “Big Picture Medicine”. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2016.

- Schumacher EF. A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Jonathan Cape, 1977.

- Szasz TD. Mental disorders are not diseases. USA Today 2000; Jan: https://www.szasz.com/usatoday.html (accessed 12 Nov 2024).

- Szasz TD. The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist 1960; 15: 113–118.

- Kajanoja J, Valtonen J. A descriptive diagnosis or a causal explanation? Accuracy of depictions of depression on authoritative health organization websites. Psychopathology 2024; 57(5): 389–398.

- Middleton H, Moncrieff J. Critical psychiatry: a brief overview. BJPsych Adv 2019; 25(1): 47–54.

- Van Os J, Guloksuz S, Vijn TW, et al. The evidence-based group-level symptom-reduction model as the organizing principle for mental health care: time for change? World Psychiatry 2019; 18(1): 88–96.

- Yeomans D, Moncrieff J, Huws R. Drug-centred psychopharmacology: a non-diagnostic framework for drug treatment. BJPsych Adv 2015; 21(4): 229–236.

- Norman AH. Recalled Experience of Death: awareness beyond the brain. BJGP Life 2023; 10 Sep: https://bjgplife.com/recalled-experience-of-death (accessed 12 Nov 2024).

Featured photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.