Patients stumble into the waiting room, propelled by a passing icy squall raging outside. They are almost uniformly Caucasian, wearing warm, waterproof coats and practical shoes. But one speaks with a Cumbrian accent, and another clearly hails from the Home Counties; two more sound Scottish, but my gradually acclimatising ear picks up both a Glaswegian rumble and an Orcadian lilt.

What does a migrant population mean at your practice? Language barriers? Housing issues? Female genital mutilation? In my previous inner city Bristol practice, with its large Somali population, these overt problems were both rife and challenging. But the migrant community there was well-defined and easily identified: flowing burkas muffled under ill-matching quilted coats bought hastily in defence of the cruel and unfamiliar British weather could at least hint at the possibility and nature of any migration-related issues lying underneath.

In the Orkney Islands, the story is different. Patients may look the same and speak easy English, but there is a substantial migrant population with its own health issues. Of the 70 islands making up the Orkney archipelago, about 20 are inhabited.1 On average in 2012-2014, 751 people entered the Orkney Islands, with a net inflow of 86.2

Migrants to the Orkney Islands encounter a myriad of challenges. In addition to the usual logistical issues of registering at a new practice and waiting for transfer of notes, or struggling to agree a management plan for a longstanding condition with a new GP, patients face the further challenge of adjusting to new structures of healthcare provision. Here, the Out of Hours service in several of the Isles (the islands around mainland Orkney) is provided by a Nurse Practitioner, and all emergency transfers to hospital from outside the main island are done via boat or helicopter. The hospital has A&E, maternity and some outpatient services, but most specialties do not have a consultant resident on the islands and many ordinarily routine diagnostic and therapeutic procedures or consultant appointments take place in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, necessitating a plane or seven hour ferry journey. The nearest ICU is in Glasgow.

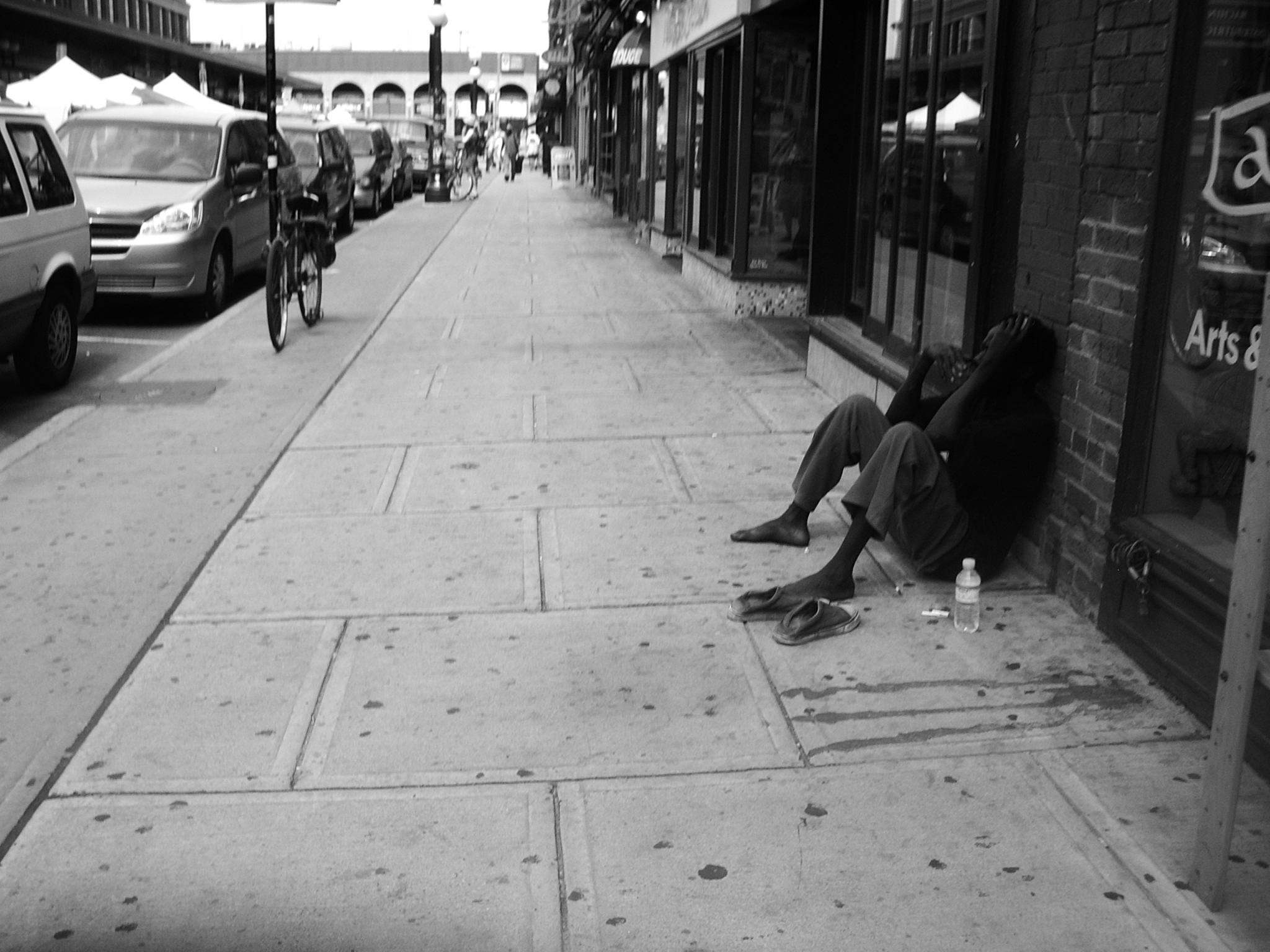

The push-pull model of migration is well established: migrants seek a new home both to leave something behind and gain a better situation.3 GPs here agree on the prevalence of mental health issues. A number of patients have moved from ‘South’ to build a new life and escape from problems at home. However, many find the relative anonymity of city life a comfort blanket in contrast to the frank inquisitiveness of an island with a population numbering a few hundred, on which everybody knows everybody’s business. People can also find that the isolation from the friends and family they wished to escape is devastating, and struggle to cope without a supportive social network. The climate can also bring its own challenges: a dazzling sun bouncing off crashing waves through the long days of a summer holiday visit does not predict long dark winters and travel-impeding tumultuous winter storms.

For rural GPs, an understanding of the potential difficulties of a migrant population is vital to managing this patient group effectively. The conversation may be clear-cut, with new patients to a practice needing advice about the logistics of accessing healthcare in an unfamiliar rural setting. However, the scope for psychological issues, which may be longstanding or newly-brewed in an environment of failed adjustment, must not be underestimated. These factors might not always be frankly discussed, but should be at the back of the mind in every consultation.

It could also be worth, in a thriving suburban practice, having the discussion with your patient who is considering an ‘escape to the country’. Is he aware that his low grade non-Hodgkins lymphoma will not be monitored by a consultant a 20 minute drive away? Has she thought about how she will get to the shops in 10 years time when her now stable knees will not allow her to hop on and off the ferry to the mainland? Are they worried that a paediatric emergency in their new baby could necessitate an air transfer? Will his ‘escape’ destroy the inner demons of his depression?

Rural settings such as the beautiful Orkney Islands offer the opportunity for a healthy, active lifestyle in a stunning environment with multiple physical and psychological health benefits. Many migrants will be delighted with their choice of move and achieve the benefits they were hoping for. However, migrant populations in a rural practice bring new challenges to GPs – just as severe but less easily recognised than with an immigrant population from far afield. An awareness of these issues is vital to managing both expectations and problems if they arise. As one of the GPs in my Orkney practice commented, “Folk come up here to get away from their problems, but they cannot get away from themselves.”

References

1. The Scottish Islands Federation. Island statistics. 2001. [Accessed 21/4/16]. Available at http://www.scottish-islands-federation.co.uk/island-statistics/

2. National Records of Scotland. Orkney Islands Council Area – Demographic Factsheet. 2015. [Accessed on 20/4/16]. Available at http://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/council-area-data-sheets/orkney-islands-factsheet.pdf

3. King, Russell. Theories and Typologies of Migration: An Overview and a Primer. Willy Brandt Series of Working Papers in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) Malmö University, 2012.