Takayuki Ando is an academic GP at the Center for General Medicine Education, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

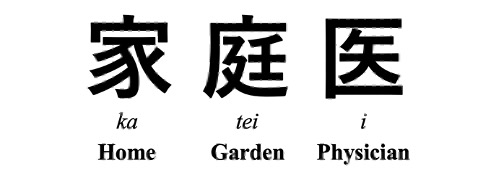

Japanese uses logographic characters (kanji), each carrying its own meaning. The English word ‘family’ is usually translated into Japanese in two ways. One is kazoku (literally ‘home + tribe’), which refers to family members themselves. The other is katei (literally ‘home + garden’), which refers more to the idea of home life. The Japanese term ‘katei-i’ (‘family physician’) is derived from ‘katei’ (‘home + garden’), where ‘i’ stands for ‘physician’ (Figure 1).

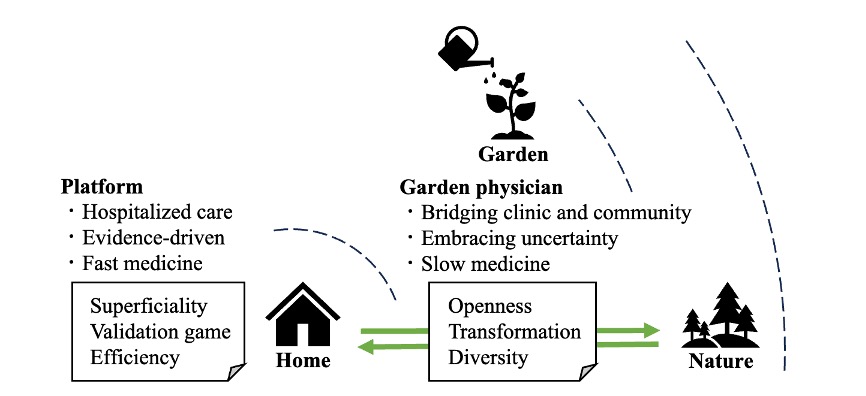

I suggest that the ‘garden’ embedded in ‘katei-i’ offers a productive metaphor for reimagining family medicine. For the family physician, the medical facility can be seen as a structured ‘home’, the community as the surrounding ‘nature’, and between them lies the ‘garden’. It is this intermediary space that may most aptly capture the role of the family physician. Accordingly, this essay is guided by the question: Why garden?

From platforms to gardens

Modern medicine is structured through multiple ‘platforms’: hospitals, outpatient clinics, nursing homes, and home visits. These platforms are indispensable; they provide structure, evidence-based practice, and efficiency. Yet in what might be called ‘fast medicine’, these very strengths risk becoming ends in themselves. Adherence to guidelines, speed of interventions, and cost-effectiveness can become performance ‘games’. When institutional maintenance becomes the goal, clinicians risk losing touch with the problems themselves.

This problem is not merely theoretical. In hospital practice, I have witnessed quality indicators pursued so vigorously that bedside care becomes hollow, or frontline clinicians lose their sense of meaning. Japanese cultural critic and media theorist Tsunehiro Uno argues in The Slow Internet that digital platforms, while promising freedom, have become cages for the game of approval.1 As an alternative, Uno proposes the metaphor of the ‘garden’. Unlike platforms, which enclose and standardise, gardens are filled with trees, insects, water, and wind — non-human presences engaged in ceaseless interaction. In a garden, one can pause, step back from efficiency and metrics, and re-encounter the problem or thing itself.2 French gardener Gilles Clément develops this further in his concept of the jardin en mouvement (‘moving garden’).3 His principle — ‘align as much as possible, resist as little as necessary’ — describes an active yet humble engagement with nature. For Clément, a garden is not untouched wilderness but a dynamic ecosystem sustained by human intervention. This resonates deeply with Uno’s critique. Together, these perspectives suggest that gardens are semi-public spaces: mediating zones where private life opens outward and external diversity enters inward. They allow for encounters that escape the game of approval and efficiency logics.

The family physician as garden physician

From this perspective, I propose reframing the family physician (katei-i) as a garden physician — one who cultivates the in-between spaces between medical platforms and lived communities (Figure 2). This role can also be understood as mediating between disease (objective pathology) and illness (lived experience).

Opening outward: from home to nature

Family physicians often step beyond institutional walls. A casual chat at a patient’s doorstep at the end of a home visit, or an informal conversation in a local bar where one isn’t even recognised as a doctor — such ‘ordinary consultations’ spark dialogues across social boundaries. In Japan, psychologist Kaito Tohata has called such moments ‘ordinary consultations’ (futsū no sōdan).4 In these encounters, the physician suspends the game of approval imposed by platforms and engages the rich lifeworld of residents as a fellow human being.

These outward steps are not incidental; they are clinical encounters in their own right. A neighbour’s worry about a spouse’s memory, or a casual mention of sleep difficulties at the bus stop, may never surface in the formal clinic. Yet these are the seeds of prevention and early intervention, germinating only when the physician inhabits the same ground as the community. In this way, opening outward is a form of slow medicine — attentive, unhurried, and woven into everyday life.

Inviting inward: bringing nature into home

At the same time, family physicians invite community voices into the medical ‘home’. Here, it is important to stress that gardens are not simple celebrations of diversity. They contain weeds, invasive species, and sometimes unwelcome presences. The gardener’s role is not to exclude them but to manage them into coexistence. Likewise, medicine must engage those often marginalised by efficient systems — the stigmatised, the vulnerable, and those left behind by the inverse care law.5 Inviting inward means not only listening to patients’ stories but allowing those stories to reshape institutional priorities. Community advisory boards, patient and public involvement in research, and co-designed health initiatives are examples of how voices from outside can alter the architecture of care. Such practices resist the homogenising force of platforms and create spaces where vulnerability and difference are not erased but integrated.

To be a garden physician is to cultivate these mediating spaces: places where chance encounters and difficult presences are not filtered out but given room to belong. This labor is neither ornamental nor optional; it is central to sustaining trust and equity in primary care.

Conclusion: toward reconstructing medicine as garden

Today’s health care is built on multiple platforms — hospitalised care, evidence-driven protocols, and fast medicine. These are necessary, yet when their preservation becomes the goal, clinicians risk becoming trapped in the game of approval, losing touch with the very problems that patients and communities face.

What we need is the metaphor of the garden: a space that blurs boundaries between self and world, allows pauses, and remains open to diversity. A garden is not controlled by its gardener but sustained by ongoing cultivation amid change. Family physicians (katei-i) are, in this sense, gardeners. They open outward into communities and invite communities inward into medicine. They traverse fast and slow medicine, disease and illness, cultivating the soil where essential questions of care can take root.

To redefine the family physician as a garden physician is to envision a future of medicine beyond platforms — dynamic, relational, and co-created with communities, much like gardens sustained by ongoing cultivation and care.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was prepared with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, specifically OpenAI’s GPT-5 (ChatGPT). The AI tool was used for language editing and for translation from Japanese to English. Prompts were provided by the first author to ensure that the content reflects the authors’ original ideas and clinical insights. We also wish to thank Akihiro Sasaki (Emergency Department, Awa Regional Medical Center, Chiba, Japan) for his generous advice, book recommendations, and daily discussions that greatly enriched the development of this essay.

References

1. Uno T. [The Slow Internet]. [Book in Japanese]. Tokyo: Gentosha, 2023.

2. Uno T. [Think as a Garden]. [Book in Japanese]. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2024.

3. Clément G. [Moving Garden]. [Book in French]. 5th edn. Paris: Sens & Tonka, 2007.

4. Tohata K. [Ordinary Consultation]. [Book in Japanese]. Tokyo: Kongō Shuppan, 2023.

5. Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971; 1(7696): 405–412.

Featured photo by Art Institute of Chicago on Unsplash.