Edin Lakasing is a GP, trainer and tutor, in Hertfordshire, England.

Introduction

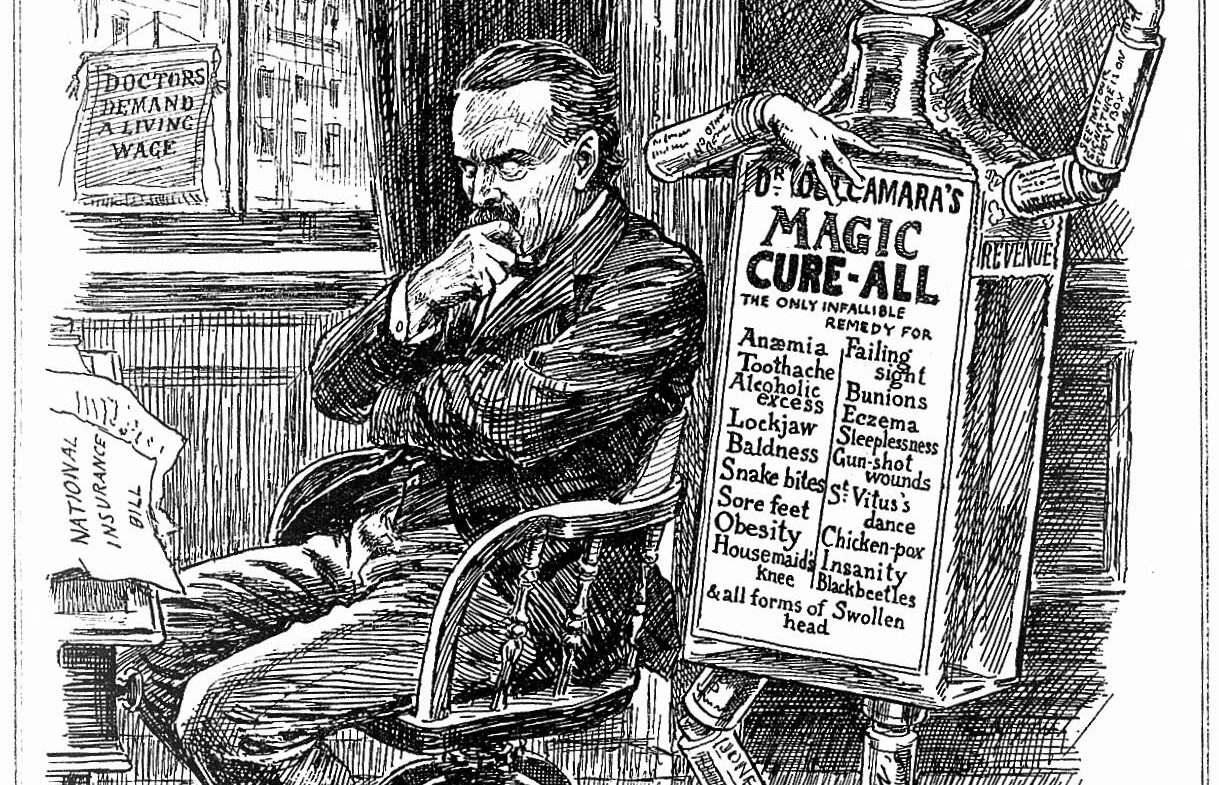

When the idea of the NHS was discussed prior to its founding in 1948, it was initially opposed by doctors, and the British Medical Association engaged in heated discussions with Clement Attlee’s first post-war government. Doctors eventually came on board, thanks to the then Health Secretary, Aneurin Bevan, shrewdly offering carrots to match the sticks; for consultants it was the right to continue private practice in their spare time, whilst for GPs it was the status of independent contractors. Despite several reconfigurations of the NHS since, these core models remain in place today. However, the independent contractor model has recently received criticism from politicians on both the right and left of the political spectrum, who have threatened its demise. I believe this that this model has served GP partners, their teams and patients well, and should a fight be needed to preserve it, that is a battle worth having. I will set this in the context of general practice’s historically hard route to recognition, and the risk posed to professional autonomy.

Difficult early years

However, the independent contractor model has recently received criticism from politicians on both the right and left of the political spectrum, who have threatened its demise.

After the formation of the NHS, an Australian GP, Joseph Collings, was tasked with observing first-hand, and reporting on, the state of UK general practice, which was published in the Lancet in 1950.1 Collings was a young man, just 31 years old at the time of publication, yet very worldly, having practised in New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Roland Petchey, reviewing the work in 1995, called it an ‘unrecognised, pioneering piece of British social research,2 but it painted a grim picture of post-war general practice, including shabby surgeries, perfunctory note-keeping, dubious therapies, and hideous workload, suggesting its prospects were poor unless a significant overhaul ensued.

Some key excerpts:

- ‘The overall state of general practice is bad and still deteriorating’.

- ‘Some working conditions are bad enough to require condemnation in the public interest’.

- Inner city general practice is ‘at best very unsatisfactory, and at worst a positive source of public danger’.

Predictably, the Collings Report was met with indignation by the GPs. However, whilst never officially recognised as such, it almost certainly gave impetus to the idea of forming the College of General Practitioners (CGP). Collings returned to Australia, where he became active in the development of academic general practice there. Sadly, he died in Melbourne in 1971 aged just 53, though his brief tenure in the UK left an indelible mark.

The existence of the CGP (Royal Charter came in 1972) did not, of course, immediately improve the esteem of GPs, and the most well-known vocalisation of the attitudes often held by consultants was made by Charles Wilson (Lord Moran). Moran was one of the UK’s most recognisable doctors, being Dean of St Mary’s Hospital Medical School, President of the Royal College of Physicians, and Winston Churchill’s personal physician.3 In 1958, giving evidence before the Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration Committee, he was asked by the chairman, essentially, whether he believed GPs and consultants were equal, to which he replied: “I say emphatically ‘No’. Could anything be more absurd? I was Dean of St Mary’s Hospital Medical School for 25 years. All the people of outstanding merit, with few exceptions, aimed to get on the Staff. There was no other aim, and it was a ladder off which some of them fell. How can you say that people who get to the top of the ladder are the same people who fall off it? It seems to me so ludicrous”.4

Those remarks gained much publicity in both the medical and general press. But I doubt that Moran, whose father and brother were GPs,3 disrespected our branch of the profession. It must be acknowledged that whilst the work of a general practitioner was extremely demanding, it was also true that at the time the academic requirements to enter it, beyond graduating in medicine, were non-existent. The stock of general practice did, however, steadily rise, another key milestone being the appointment of Richard Scott to the first Chair of General Practice in Edinburgh in 1963. GPs such as John Fry and Julian Tudor Hart began to publish vital community-based research. The improved recognition was not entirely due to academic achievement, however. As medicine became more technologically advanced, general practice successfully absorbed the bulk of the management of hypertension, diabetes and asthma from secondary care, and primary health care teams evolved to keep pace.

Benefits of the independent contractor model

In many ways this model is a working example of social democracy, a label often used in continental Europe for centrist politics and political parties, but which has never taken off in English-speaking countries. Essentially, whilst working within the NHS, there is some entrepreneurialism encouraged, and latterly financial incentives through quality targets and enhanced services. Perhaps the most important aspect has been the flexibility for individual practices to adapt to the populations they serve, something particularly important given the UK’s enormous diversity, which goes far beyond its ethnic mix. For this is also a country where GPs do home visits by boat to patients on remote islands, where there are post-industrial towns with dire deprivation, and where there are streets where only billionaires live.

Perhaps the most important aspect has been the flexibility for individual practices to adapt to the populations they serve, something particularly important given the UK’s enormous diversity, which goes far beyond its ethnic mix.

But this model is by no means free from political assault. The current Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting has stated that he would tear up the GP contract and make us all salaried employees of the NHS.5 It is not an altogether surprising opinion from someone quite far left on the political spectrum. What is more telling is that a recent Conservative Health Secretary, Sajid Javid, just a year previously, proposed the same.6 The fact that Streeting and Javid are at diametrically opposite ends of the political spectrum, yet espouse identical views suggests that where general practice is concerned, yet another radical overhaul is likely to be proposed whichever party forms the next government, and that the resolve of GPs will be tested once again.

Streeting and Javid are both likeable and articulate men who have risen from humble backgrounds to prominent positions in public life. But their terrible miscalculations show a lack of appreciation for how much we do, and how cost-effective our service is. It also suggests a reductionist view of primary care and a hospital-centric vision of healthcare planning. For the dubious benefit of paying you and I a little less than we currently earn, would they really pass the cost of staff and utilities to the taxpayer? Would they also lacerate incentives such as the enhanced service for minor surgery, and send patients to join a long queue for hospital-based elective surgery at several times the cost? And what of those services whose tariffs have slipped below the NHS radar, like cremation forms and teaching students, if indeed we were to be banned from all private work? It would, first and foremost, be a tragedy for patients, who will have a far more basic primary care, denuded of its extras. Hospitals would face being flooded with precisely those mid-technology areas ceded to general practice. Given that the waiting list for elective care now stands at 7.2M,7 they would certainly fail. And general practitioners, who have moved impressively far from the depressing scenarios described by Collings, would take a massive step back by losing much of what makes our job interesting, as well as losing our autonomy.

The independent contractor model for general practice is one of the good, under-rated aspects of the NHS that rarely hits the headlines. Given general practice’s hard fight for peer recognition, it is particularly important for our professional autonomy and business flexibility. It is not ‘broke’, and we must reject all offers to dismantle it.

References

- Collings JS. General practice in England today: a reconnaissance. Lancet 1950; i: 555-585.

- Petchey R. Collings report on general practice in England in 1950: unrecognised, pioneering piece of British social research? BMJ 1995; 311: 40-42.

- Lovell R. Churchill’s Doctor: A Biography of Lord Moran. Royal Society of Medicine: ISBN-10: 1853151831.

- Curwen M. “Lord Moran’s ladder”: a study of motivation in the choice of general practice as a career. J Coll Gen Pract 1964; 7:

- Taylor H. Labour ‘would tear up contract with GPs’ and make them salaried NHS staff. The Guardian, 7 Jan 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/07/labour-would-tear-up-contract-with-gps-and-make-them-salaried-nhs-staff (accessed 17 Mar 2023).

- Tilley C. Majority of GPs should be employed by trusts, says Javid-backed report. Pulse, 4 Mar 2022. https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/politics/phase-out-gms-contract-by-2030-and-employ-majority-of-gps-by-trusts-urges-think-tank/ (accessed 17 Mar 2023).

- NHS England. Consultant-led referral to treatment waiting times 2022-23. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/rtt-waiting-times/rtt-data-2022-23/ (accessed 17 Mar 2023).

Featured image: A figure comprised of medicine bottles and tablets, representing the patent medicine business, dances behind a pensive Lloyd George; representing attitudes to the introduction of the National Insurance Act of 1911. Wood engraving by B. Partridge, 1912.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. In copyright

Obtaining a GC license is a clear indicator of a contractor’s professionalism and dedication to excellence.