Catherine Gaynor is a Salaried GP in Newham and a Net Zero Clinical Lead for North East London Integrated Care Board. She is a Member of Plant Based Health Professionals UK.

Fourteen years ago, I watched the drama-documentary-animation hybrid film: The Age of Stupid. This is set in a climate-ravaged 2055, and features a last-surviving human who has been entrusted to archive human records. He is reflecting on news footage demonstrating the devastation of human-caused climate change (made with real footage from around 2008) and asking — why didn’t we act?

Fast-forward to March 2023 and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has just published its sixth report, and warns ‘Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health (very high confidence). There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all (very high confidence)’ and ‘Those who contributed the least to climate change are often the most vulnerable to its impacts’.1,2 It is critical for equality, health, and the environment that we act.

One simple but very powerful action is for the NHS and our clinicians to start talking about eating more plants and less meat. One-third of all global greenhouse gases are from our food system; of that third, 55% is derived from livestock and 40% is solely enteric fermentation from the guts of ruminants.3

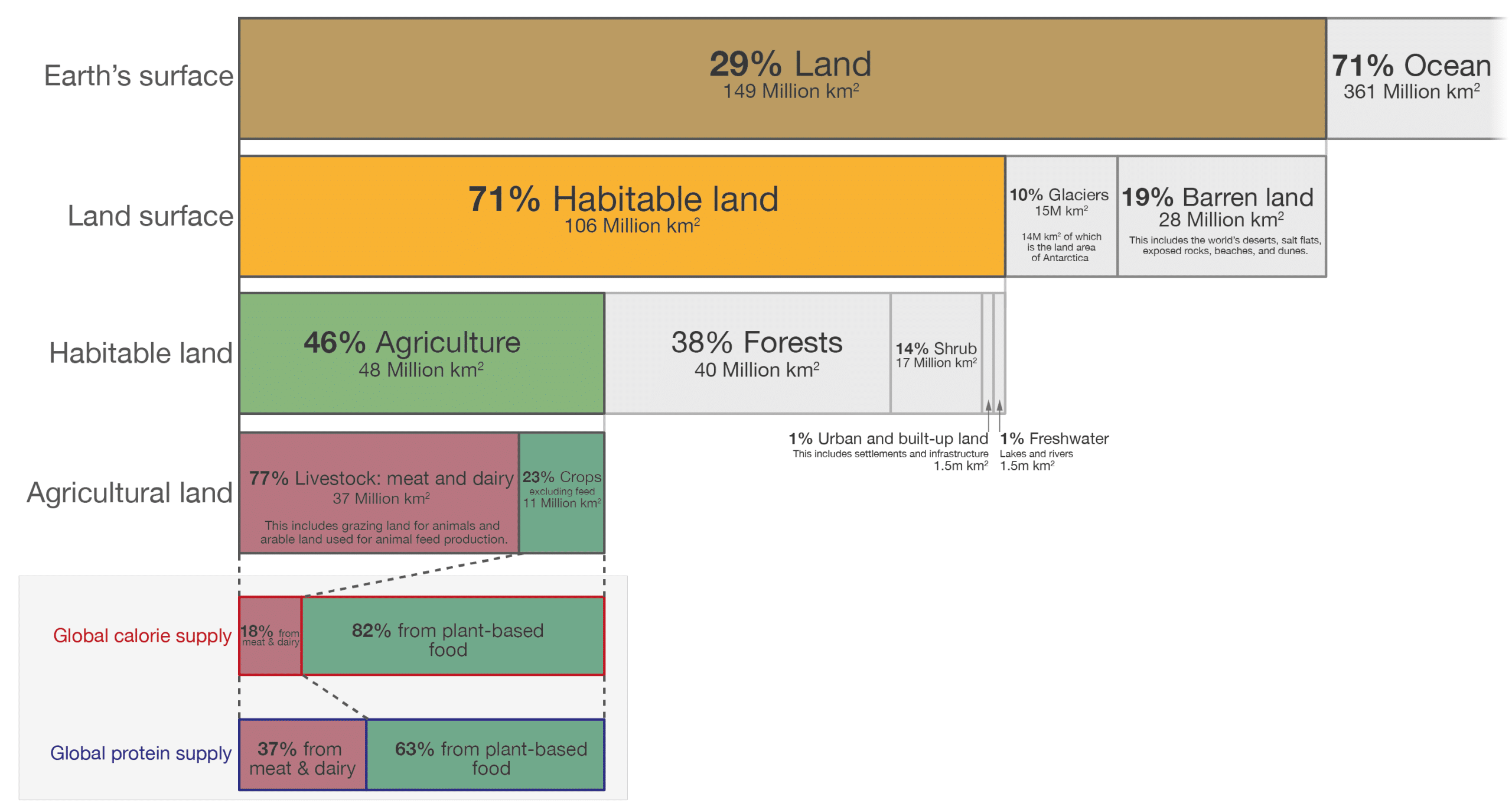

When you combine the land used to grow crops for animal feed with that used for livestock it is at least 77% of all farmlands. With this giant carbon and land hoofprint it is estimated that meat and dairy provide 18% of global calories (Figure 1).4

By reducing our dependence on animal products we are not only able to feed more people and reduce emissions but also reduce non-communicable diseases. Diets high in animal products tend to be high in saturated fat, salt, and processing, and low in fibre. The Lancet countdown on health and climate report states that of the 11.5 million diet-related deaths in 2019, 2 million were ‘related to red and processed meat and dairy’, and 93% of these were in high and very-high Human Development Index countries, like the UK.5

In 2021, the UK government commissioned an independent review to write a National Food Strategy. What are two of the recommended ‘Changes needed to the national diet by 2032 to meet health, climate and nature commitments’? To increase fruit and vegetable consumption by 30%, and to reduce meat consumption by 30%.6

In the UK, our government dietary recommendations come to us most simply via the Eatwell Guide 2016. This visual aid, pie chart meets dinner plate, has a slice representing each macronutrient group. Apart from a major shift away from fat, a more subtle 2016 change was the ‘Meat, fish, eggs and beans’ pie slice becoming ‘Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins’, along with the less subtle statement: ‘Eat less red and processed meat’.7 Albeit in small print, it is a definitive message. Are we delivering it?

“By reducing our dependence on animal products we are not only able to feed more people and reduce emissions but also reduce non-communicable diseases.”

Recently I realised the NHS website and British Dietetic Association (BDA) iron pages were unreservedly recommending red meat as a good source of iron. This was without mention of either the climate crisis or health concerns.

The NHS website has a page dedicated to the risk of bowel cancer from eating too much red and processed meat.8 The UK Government website on climate and health states: ‘A diet rich in plant-based foods, and lower in animal source foods … has benefits for health and the environment’. They state that adherence to the Eatwell Guide could cut emissions by 30%.9

The BDA has done an extensive piece of work on sustainable diets called the One Blue Dot toolkit: ‘By making dietary changes, it’s win-win for the planet and health’.10 One of the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) recommendations to the Government includes a ‘20% shift away from all meat by 2030, rising to 35% by 2050, and a 20% shift from dairy products by 2030’.11 Yet, regardless of everything said so far, here we have two of our commonly used national online resources advocating red meat without caution.

All those years ago (after watching The Age of Stupid), I changed to a vegetarian diet and my mum worried: ‘But you will be so pale’. Despite Popeye’s best efforts, the narrative of strength and iron having to come from meat has been continually reinforced by society and medicine. In primary care, low iron stores are a frequent clinical scenario and the conversations go: ‘Are you vegetarian? Do you eat red meat?’

Iron quantities are plentiful in plant diets; however, haem iron from meat is more readily absorbed and plant diets are rich in phytates, which reduce absorption. There is a logical risk, however iron deficiency prevalence (in industrialised countries) has not been found to be higher in non-meat-eating groups. You can read about this in the iron section of the BDA’s One Blue Dot dietitians reference guide.10

There are habits we can advise to maximise iron absorption, like avoiding tea and coffee around mealtimes and adding vitamin-C rich food. There is also evidence (hence the link to bowel cancer) that haem iron is associated with inflammation, DNA damage, and carcinogenesis.12 So, the dietary questions we should be asking our iron-deficient patients are: ‘Do you eat dark green vegetables, pulses, beans, nuts, seeds, and fortified breakfast cereals? Are you having tea and coffee with your meals? And do you eat citrus fruits?’

I contacted the NHS website about their iron page, and they indicated the BDA was their source. I contacted the BDA who were amenable to editing the page to include the Eatwell guidance. The NHS website duly followed. This initially felt like an achievement, but soon turned to exasperation. The changes were just a drop in the ocean of the hundreds of online factsheets sent to patients every day without regard to sustainability.

Another CCC recommendation to the Department of Health and Social Care is to:

‘Deliver climate policy that also has health benefits, such as active travel, access to green spaces, air quality, better buildings and healthier diets. This could be done by reviewing ways in which DHSC public guidelines could integrate messages that strengthen and make more evident the co-benefits of good nutrition and exercise for both health and for the environment.’11

Of course, it can’t be and isn’t just the remit of health to promote sustainable healthy eating. It needs to be enabled by our surroundings and work is happening in local authorities with retail, schools, local growing schemes, food poverty action plans, and supply chain progress.

For too long there has been a tendency to consider human and planetary health separately. Food is a perfect example of where you can see the two are fundamentally linked. It is one of our greatest levers to combat both the climate and health crisis. Every online resource is an opportunity to promote eating sustainably, active travel, and cultivating green space.

I finish with an EAT-Lancet quote: ‘A diet that includes more plant-based foods and fewer animal source foods is healthy, sustainable, and good for both people and planet. It is not a question of all or nothing, but rather small changes for a large and positive impact’.13 Or, as I would advocate — eat mainly plants, eat the rainbow, choose wholemeal carbohydrates, and only eat meat for a treat.

Further reading

NEL Health Creation scholar 2023. University of Winchester – Plant-based nutrition; a sustainable diet for optimal health 2020

References

1. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Synthesis report of the IPCC sixth assessment report: summary for policymakers. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

2. IPCC. Sixth assessment report: synthesis report. 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/press/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SlideDeck.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

3. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Emissions and climate change. In: Statistical yearbook 2021. 2021. https://www.fao.org/3/cb4477en/cb4477en.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

4. Ritchie H, Roser M. Land use. 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/land-use (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

5. Romanello M, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022; 400(10363): 1619–1654.

6. National Food Strategy. National Food Strategy independent review: chapter 16 – the recommendations. 2023. https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

7. Public Health England, Welsh Government, Food Standards Scotland, Food Standards Agency in Northern Ireland. Eatwell guide. 2016. https://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Goodfood/Documents/The-Eatwell-Guide-2016.PDF (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

8. NHS Digital. Red meat and bowel cancer risk. 2021. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/red-meat-and-the-risk-of-bowel-cancer (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

9. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Climate and health: applying All Our Health. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/climate-change-applying-all-our-health/climate-and-health-applying-all-our-health (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

10. British Dietetic Association. Eating patterns for health and environmental sustainability: a reference guide for dieticians. 2020. https://www.bda.uk.com/uploads/assets/539e2268-7991-4d24-b9ee867c1b2808fc/a1283104-a0dd-476b-bda723452ae93870/one%20blue%20dot%20reference%20guide.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

11. UK Climate Change Committee. Recommendations for Defra. In: Progress in Reducing Emissions: 2022 Report to Parliament. 2022. https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Progress-in-reducing-emissions-2022-Report-to-Parliament.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

12. V Fiorito, D Chiabrando, S Petrillo, et al. The multifaceted role of heme in cancer. Front Oncol 2020; 9: 1540.

13. EAT-Lancet. EAT-Lancet Commission brief for everyone. 2023. https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/01/EAT_brief_everyone.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2023).

Excellent and much needed discussion on how we consider food and their nutrients. Plant-based diets can easily be optimized to provide sufficient iron, whilst having the benefits of lower the risk of a number of chronic conditions and being more sustainable for our planet. Let’s get our guidelines updated to reflect the current science and evidence. Thank you for writing this.