Tim Senior is a UK trained GP working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health in Australia. He is on twitter: @timsenior

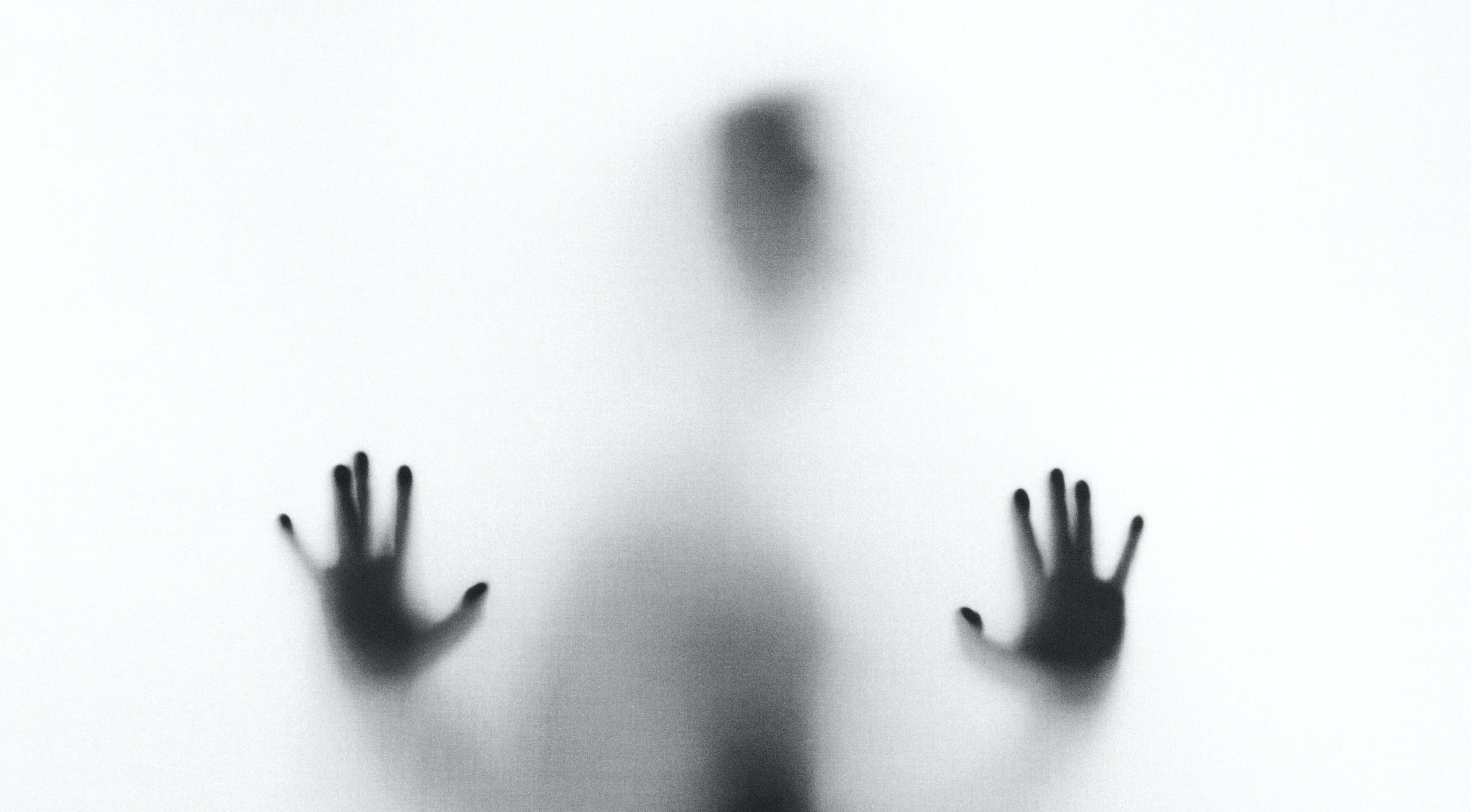

Given the sheer number of patients seen by GPs, it’s perhaps surprising that a large proportion of our work is completely invisible. To policy-makers and funders peering in our surgeries through the hazy window of data generated in a consultation, there will be the number of patients seen, and for some of them a coded diagnosis, for some a prescription generated. In Australia, the data available mostly comes through Medicare claims, the government health insurance system, which says a lot about the length of the consultation in 20 minute blocks, and a little more about a test or procedure, whether that’s spirometry, a pregnancy test, or a removal of a skin lesion.

The reporting of a limited set of nationally important diagnoses, some risk factors and some quantitative measures leaves a lot more of the work invisible.

The reporting of a limited set of nationally important diagnoses, some risk factors and some quantitative measures leaves a lot more of the work invisible. So many problems for patients – migraines or menopausal symptoms might be two examples among hundreds – are managed by GPs which don’t show up in reports, though they are usually obvious to patients.

This leads to the perception that what GPs do is related to diagnosis, referrals and prescriptions. To this, we might add preventive health, which shows up in data as immunisation coverage, and as blood pressure numbers and cigarettes smoked. The essence of preventive care, though, is invisibility. If we do our job well, there’s a large number of heart attacks, strokes, lung cancers or influenza infections that never get seen by the health system, because they don’t happen.

The work that achieves this invisibility is also invisible. Management of blood pressure is so much more than a measurement and a prescription. There’s thinking about the most appropriate medication, usually in the context of their other medications, and other medical conditions; there’s determination of risks and benefit, and more complex still, discussion of the risks and benefit tailored to that particular patient; there’s also specific decisions about monitoring and follow up.

Some of our most complex work becomes invisible by hiding it behind simple two word phrases like “brief intervention” or “motivational interviewing.” Complex tailored discussions about behaviour change of deeply ingrained habits are hidden behind the language of a simple intervention performed on a passive patient. This language also hides the active individuality of the patient’s involvement.

It is this invisible work that holds the health system together.

Just about every consultation is made up of mostly invisible work, often even invisible to ourselves, as we establish the professional habits along which our minds run. Every consultation has a series of high-stakes complex decisions – what serious condition might I be missing here? What else is going on for this person? Have they understood? How can I continue to establish rapport? Even just reassuring someone that their symptoms are not serious is therapeutic. It’s not unusual that this work results in a diagnosis classified eventually as “a minor illness” or even no pathology at all – invisibility as diagnosis!

It is this invisible work that holds the health system together. It is the relationship GPs have with individual patients that is where public health measures touch the ground. Without a trusted relationship with GPs, immunisation and screening programs are less effective. Without GPs standing alongside patients, helping them navigate agencies and referrals and hospitals, explaining the decisions of others, the health system becomes an impenetrable network of closed doors.

The other body of work that seems to have become invisible is that of the much-missed Barbara Starfield, demonstrating how effective primary care is, in keeping people healthy, and in promoting fairness and equity.

Ironically, it may be that our work becomes most visible when we are no longer there to be seen.

Featured Photo by Stefano Pollio on Unsplash

Thank you for putting into words – and helping to make visible – the invisible work of general practitioners. I especially agree with your statement that :without a trusted relationship with GPs immunisation and screening programs are less effective” as this has very much been brought home to me in the case of Covid vaccinations though I would broaden it to nurses and pharmacists as well as GPs. There was a lot of funding and resources put into setting up Covid vaccination clinics including pop-up outreach clinics in 2021 and lots of my patients from refugee and newly-arrived communities got the first two Covid vaccinations with them. But they had no relationship with the vaccinators- who didn’t spend much time with them and never mentioned the possibility/probability that regular Covid vaccinations would be likely to be required to maintain reasonable immunity as with influenza vaccinations. I’ve found so many of my patients who got their first two vaccines not at our practice have been much less receptive to getting their next Covid vaccines – putting them at higher risk for more severe Covid infection. I think now it would have been better to have put more resources into pharmacies and general practices to vaccinate everybody. And I agree it is impossible from the outside to really understand what GPs do – but in Australia the Uni of Sydney’s BEACH program which ran from 1998 to 2016 was probably the best ever study internationally of primary medical care and its data is still being used all the time. It’s funding was ceased by the Abbott government. I hoped of Labor got into government that we might get back to the BEACH but sadly this Labor government and Pur current Health Minister seem to be quite hostile to general practice especially in their gaslighting campaign re Medicare.