What would your dream job look like? It might not be in UK general practice as it is currently, but how much would need to change before that felt less of a stretch?

Work is generally a good thing,1 and jobs in health care have the potential to be more rewarding than most. In practice, though, enough things get in the way that the dream has become one of those recurring ones in which you’re going on holiday but no matter what you do, the suitcase won’t quite shut.

We regularly face a level of demand that we don’t have the resources to meet, carry a high level of responsibility within a system that restricts our agency, and do a lot without often feeling as if we’ve done much good.

To some extent we can fight these frustrations by working harder, bending the rules, and cutting back in our personal lives. When things still feel dicey despite this, though, and when we have to keep it up day after day, it’s unsurprising when we end up feeling tired, resentful, and just a little less human, and the day’s patients start to look like the next wave of zombies massing outside the gates. We gradually downgrade our aspiration from thriving to functioning to surviving, and our only options look like pushing through or getting out.

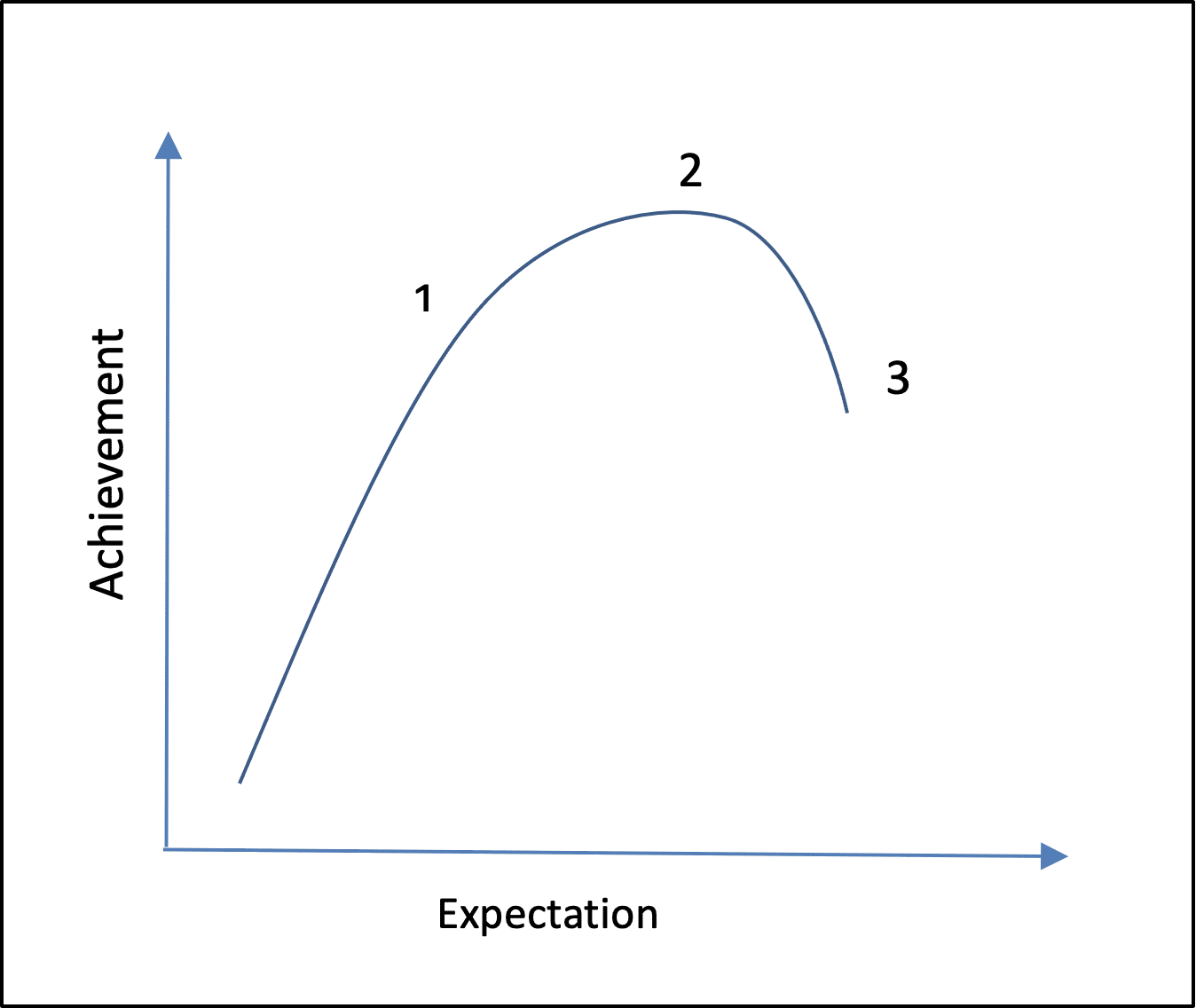

Figure 1 illustrates this: it is a crude approximation of the relationship between demand and response in a number of systems, which in our case equate with, respectively, expectation and achievement.

Up to a point (1), we simply do more as more is expected of us. Past this point, however, we can go the extra mile but achieve only a little more. When we are already doing all we can (2) but expectations continue to increase, we quickly become less effective. Significantly, the point of maximal achievement (2) is right next to that of system failure (3).

Experience suggests that general practice, the NHS as a whole, and a growing number of individual doctors are all moving from point 2 to point 3. The idea of pushing through has a certain heroic appeal despite being clearly doomed, perhaps only because, like Macbeth, we don’t have the energy to do anything else.2

We know that a number of personal characteristics are associated with resilience among primary healthcare professionals;3–5 it may even be possible to inculcate them through training. The danger of seeing this as a solution, though, is that it misses several crucial points.

First, the qualities of resilient doctors are simply those conducive to reasonable psychological health in general,6 and the majority of people already cope well with any difficulties in their lives.7 Second, most of the variation in individual responses to adversity cannot be accounted for by the presence or absence of ‘resilience’ traits.7 At best, promoting particular behaviours or attitudes might allow us to adjust marginally the position of transition points on our curve, but its shape and our place on it would remain the same.

“Simply going on as we are means marching into oblivion.”

Third, and most importantly, resilience is about responding adaptively to crises, not sustaining an unrealistic workload indefinitely. On the graph, it is this adaptability that give us the wiggle-room to stretch from point 1 to 2 when we have to, but 1 represents the highest level of demand that can be maintained on a regular basis without damaging the system.

If we need to be creative, solution-focused, and hopeful just to make it to the end of an average day, there’s something seriously wrong at a higher level than our personal coping skills. There is a danger that we normalise and even celebrate the ability to tolerate chronically and inappropriately high expectations, when we should instead be challenging them.

Look again at the steep slope between points 2 and 3 in Figure 1, though: even a small reduction in demand can quickly improve matters. In other words, if you want to achieve more at this point, take off some of the pressure! In order to be working sustainably, though, we need to push expectations back further, from point 2 to 1.

In terms of appointments per day, or documents filed, this would mean achieving less, but it would give us back the flexibility to respond to peaks in demand and finally allow us to shut the suitcase, to work at a pace that is more satisfying because it achieves something meaningful for our patients.

For individual GPs, the most adaptive response to an unmanageable workload may be to get out while you can. All work is not toxic, though, and it may also be that relatively small changes in our expectations, or indeed those of our masters, would allow many of us to work more effectively and enjoyably, to remember our own humanity and that of our patients.8 Simply going on as we are means marching into oblivion. If instead we want to thrive in practice, we need to find a way of keeping behind the curve rather than ahead of it.

References

1. Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: the Psychology of Happiness. London: Rider, 2022.

2. Shakespeare W. Macbeth: Act 3, Scene 4. In: The Arden Shakespeare Complete Works. London: Bloomsbury, 2013; 786–788.

3. Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685261.

4. Eley E, Jackson B, Burton C, Walton E. Professional resilience in GPs working in areas of socioeconomic deprivation: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X699401.

5. Matheson C, Robertson HD, Elliott AM, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals working in challenging environments: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685285.

6. Eley DS, Cloninger CR, Walters L, et al. The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing wellbeing. PeerJ 2013; DOI: 10.7717/peerj.216.

7. Bonanno GA. The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience is Changing the Way We Think About PTSD. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2021.

8. Martin L, McDowall A. The professional resilience of mid-career GPs in the UK: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2021; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0230.

Featured photo by Lucie Delavay on Unsplash.