The links between my passion for Bronze Age Greece and working in modern-day practice have never felt tangible, until I recently took time to reflect. Look close enough and you’ll find the threads of history woven throughout medicine and, like all history, if we want to progress, we must strive to learn from it.

Despite forming the oldest civilisations of Europe (from around 3500 to 1000 BCE), the Bronze Age Greeks were incredibly sophisticated.1 Although medicine has advanced through the millennia, some parallels remain with our ancestors. Within our overstretched NHS, as we strive to meet demand using emerging technology and multidisciplinary teams, are we neglecting some basic principles — issues dating back to Bronze Age society — that are essential to modern health care?

On my travels around Greece, three main lessons from the Bronze Age relevant to modern practice have stood out to me.

Health inequalities prevailed and persist today

Stark health inequalities were prevalent in Bronze Age Greece. Approaching the palace of Mycenae, you would have been struck by the impressive masonry blocks, so huge that ancient Athenians 2000 years later believed the walls were constructed by cyclopes (one-eyed giants). Imposing lionesses guarded the gateway, adorned with gemstone eyes.

In the centre of the palace was the throne room where the king resided. His status was earned through prowess in warfare and hunting; his helmet decorated with boar’s tusks as a testament to his skill. The palace elite were buried with great riches, most notable being their golden masks, like the one famously attributed to King Agamemnon, who led the Greeks in the Trojan War.2

The remains of these rulers were muscular and sturdy, showing they were well nourished. They had clearly received medical attention too — a woman from the palace household was found with a well-healed humeral fracture.3 Palace physicians mainly learned through observing injuries obtained in combat and made pioneering innovations to manage certain injuries. Meanwhile, people living beyond the palace were shorter, had dental lines indicating periods of starvation, and some had poorly healed fractures.3

It’s sobering to consider that thousands of years later, these health inequalities persist and are actually widening.4

Infectious diseases were rife and are once again on the rise

Infectious diseases were a constant threat in Bronze Age Greece.3 Within the palaces, the importance of fresh water and sanitation was recognised, with sewers, baths, and toilets built at several sites.1,5 However, only some had access to these luxuries. A mass grave was recently found in the Peloponnese, containing the remains of multiple people thought to have died from an epidemic, likely facilitated by poor sanitation and sea trade.3

Pioneering Greeks explored beyond the Aegean Sea, making global connections. For instance, an exquisite fresco from Akrotiri (a settlement believed to be the inspiration for Atlantis) depicted monkeys, identified as Hanuman langurs from the Indian Subcontinent.6 Meanwhile, Cretan pottery produced in the labyrinthine palace of Knossos, has been found in Egypt.1

Compare this to the 21st century and we find infectious disease is a rising issue in modern practice: global travel continues to aid the spread of diseases, outbreaks of measles have recently been facilitated by poor vaccine uptake,7 and bed bug infestations have made the headlines, perhaps a reflection of widening health inequalities, with poverty driving some health problems.

Community support was integral to self-help in the Bronze Age, but risks being lost in modern society

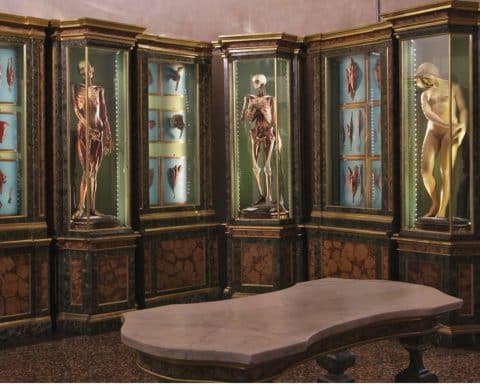

With limited scientific understanding of medicine, Bronze Age Greeks often relied on the wisdom of community elders, their own innovations, and religious worship.1,3 Self-help was particularly important among rural communities, with barbers and blacksmiths possibly applying their skills to minor surgery and dentistry! Priest-healers cast spells, while the clay model of a deformed hand, possibly affected by leprosy, was recently found at a healing sanctuary in Crete.3 Within the palace of Knossos, two female figures holding snakes were excavated, which were potentially linked to a healing cult, given that snakes later became symbolic of the Greek god of healing, Asclepius.1

Luckily we don’t rely on our local barber to perform minor surgery in our modern world! However, people frequently live in isolation from their community,8 which can detract from self-help and risk potentiating overmedicalisation of illness.9 Social prescribers are working to strengthen links within communities, which may include support derived from religious groups (like in prehistoric Greece), but often the most vulnerable aren’t reached.10

Positive changes in action

Having reflected on ancient problems that persist in modern-day society, alongside the benefits of social connections that are being lost, what can we do in response? First, we could look for inspiration from GPs and their wider teams who are working to tackle these issues.

Deep End GPs who serve the most deprived communities are working together to address the challenges of multimorbidity, fragmented care, and pressures on emergency services and health inequalities.10 Considering the rise of infectious diseases, several medical students recently published their work promoting vaccinations while on a GP placement. By sharing videos with clinicians to support discussion of vaccines and displaying posters to educate the local community, they were able to improve vaccination rates.11

Considering community support, social prescribers are working to build social connections and empower people to take personal responsibility for their health.12 A WiseGP story recently highlighted how occupational therapists could empower people with chronic pain, fatigue, and mood problems to improve their functioning and independence.13 Along with helping individuals, these approaches could reduce pressures on the wider healthcare system.

Should we be agents of social change?

As we seek solutions from technology to tackle problems faced in modern health care, perhaps we should also be reflecting on lessons from our past. Social networks that once supported the health of our society are becoming fragmented, while health inequalities, poverty, and disease outbreaks that once impacted the prehistoric world persist today.

Some may feel that driving political change is beyond the scope of frontline GPs. However, with our expertise, do we have a wider responsibility as advocates for the health care of our society? Should we be pushing for improvements to tackle underlying inequalities that perpetuate illness? With inspiration from Bronze Age Greek pioneers or modern-day GPs leading change in the face of adversity, perhaps we should all look to make our voices heard as agents of social change?

References

1. Shapland A. Labyrinth: Knossos myth & reality. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2023.

2. Cacouri A, McCabe R, Guare J, French LW. Mycenae: from myth to history. New York, NY: Abbeville Press, 2016.

3. Arnott R. Healing and medicine in the Aegean Bronze Age. J R Soc Med 1996; 89(5): 265–270.

4. The King’s Fund. Health inequalities in a nutshell. 2021. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/health-inequalities (accessed 19 Dec 2023).

5. Psarros N. Akrotiri: guide to the prehistoric town. Santorini: Private Edition, 2017.

6. Pareja MN, McKinney T, Mayhew JA, et al. A new identification of the monkeys depicted in a Bronze Age wall painting from Akrotiri, Thera. Primates 2019; 61: 159–168.

7. NHS Digital. Childhood vaccination coverage statistics — England, 2021–22. 2022. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-immunisation-statistics/2021-22 (accessed 19 Dec 2023).

8. Galvez-Hernandez P, González-de Paz L, Muntaner C. Primary care-based interventions addressing social isolation and loneliness in older people: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2022; 12(2): e057729.

9. Mathew R. Rammya Mathew: tackling overmedicalisation must become a political priority. BMJ 2023; 381: 1075.

10. British Medical Association. Deprivation meets inspiration. 2023. https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/deprivation-meets-inspiration (accessed 19 Dec 2023).

11. Buck JL, Hong ASJ, Nixon J, et al. Further improving MMR immunisation uptake [comment]. 2020. https://bjgp.org/content/further-improving-mmr-immunisation-uptake (accessed 19 Dec 2023).

12. Pollard T, Gibson K, Griffith B, et al. Implementation and impact of a social prescribing intervention: an ethnographic exploration. Br J Gen Pract 2023; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0638.

13. WiseGP. Developing a new service for people with chronic pain. https://www.wisegp.co.uk/chronic-pain-support (accessed 19 Dec 2023).

Featured photo by Annabelle Machin: Replicas of Bronze Age Greek artefacts, including the Snake Goddess of Knossos, Crete.