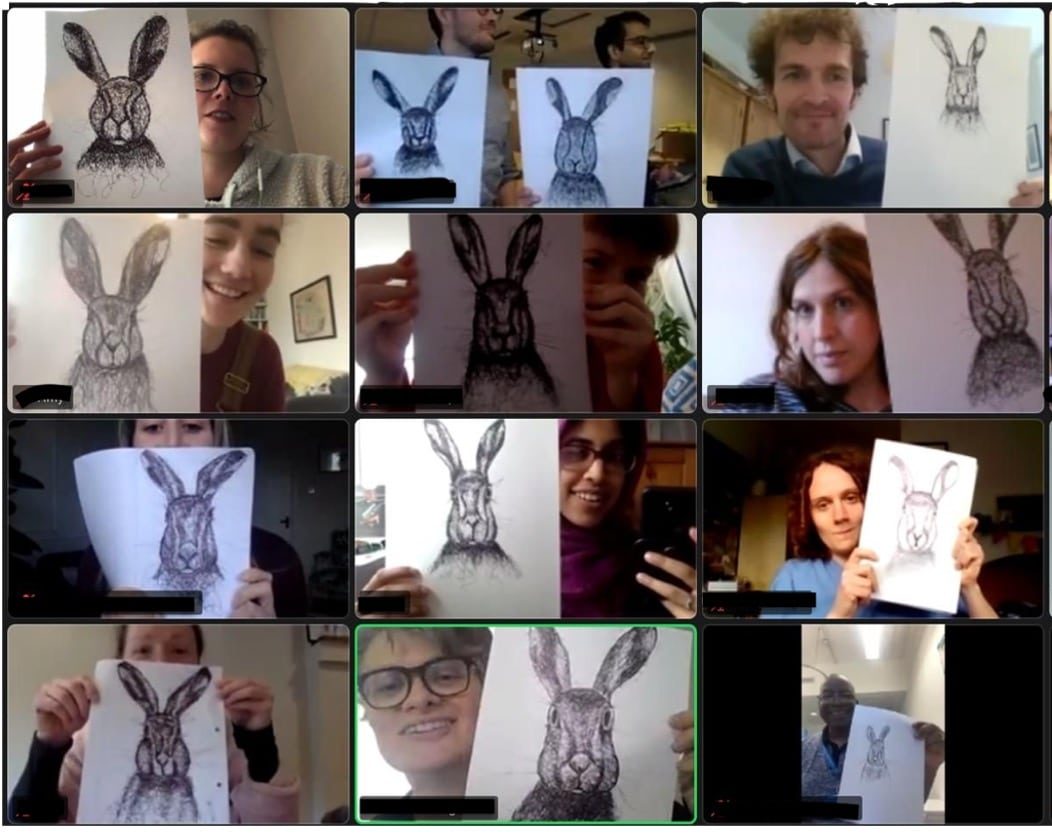

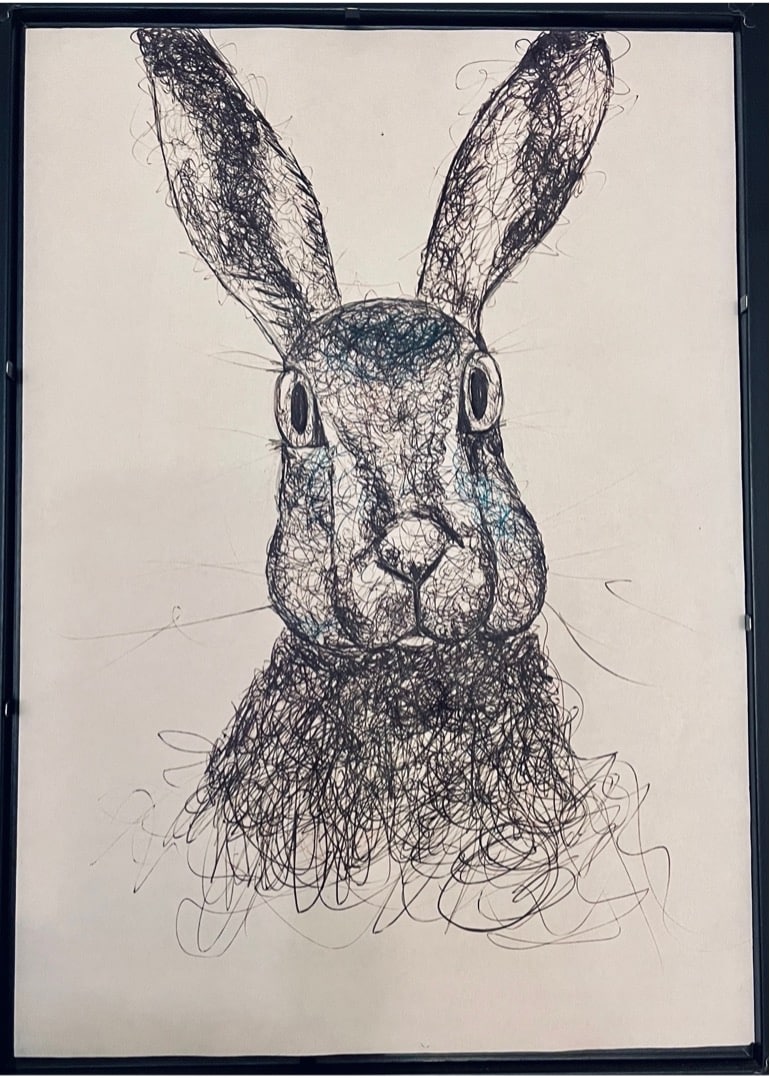

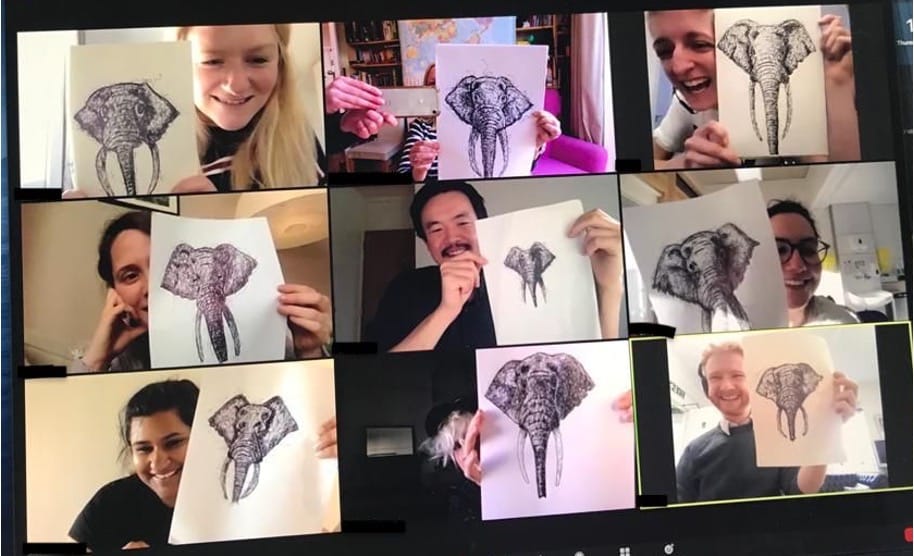

It is March 2021. We’ve endured two lockdowns and a year of remote learning. We should be holding our Easter awayday for the GP registrars, usually a time of connection and togetherness, celebrating our registrars’ progress, but instead I am peering into my laptop.

But in a miracle of communication, an artist on the other side of the country is teaching us to draw a hare. As we scribble away amid the stress and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic we are laughing and connecting.

Although not natural bedfellows, art-making has skirted around the fringes of medical education for over half a century. In his seminal 1959 ‘two cultures’ essay, CP Snow described how the sciences and humanities were pitched against each other, later writing how the arts were needed to bridge the culture gap and humanise the medical profession.1,2 This birthed the medical humanities movement, and collaborations with artists swiftly followed.

Utilising techniques used by art history students, medical students were invited into museums to view carefully curated artworks to improve their observational skills, and initially the interventions showed considerable success.3,4

But later the pressure mounted to justify art and art-making in medical curricula, and it turns out empirical data for the visual medical humanities is hard to measure, with little evidence for long-term educational outcomes.5,6

It looks like because the medical humanities ‘defy easy metrical appraisal’ they risk ongoing marginalisation and they are increasingly viewed as an optional bolt-on.7,8 Medical education just got a bit drier.

However, across the world are examples of medical educators looking beyond their measuring sticks and embracing the immeasurable. Heartfelt Images, conceived by Carol Ann Courneya in British Columbia, is a collection of art produced over a 16-year period by dental and medical students attending an introductory course on cardiology.9 She argues passionately that it is the very lack of structure, competencies, and assessment that gives art-making value in medical education.

Meanwhile in Pennsylvania, Michael Green uses comic-making, and its intriguing possibilities to create layers of meaning through humour, art, and metaphor. In a course Green facilitated, medical students were invited to make their own comics about a formative training experience; he found it to be a uniquely effective vehicle for reflecting on professional identity, a safe arena that allowed freedom and honesty to express challenging thoughts.10

In Wisconsin, doctors in training were invited to attend a comic-drawing session on stressors in medicine; participants found it a safer way to share stressful situations than conventional routes, and several participants shared an experience for the first time.11

In California, Joanna Shapiro found that art-making had huge potential to help students explore their feelings around professional identity formation, isolation, and need for connection.12 She theorises that the non-verbal creative act facilitates more positive emotions, more connectedness, and more hopefulness than verbal discussions.

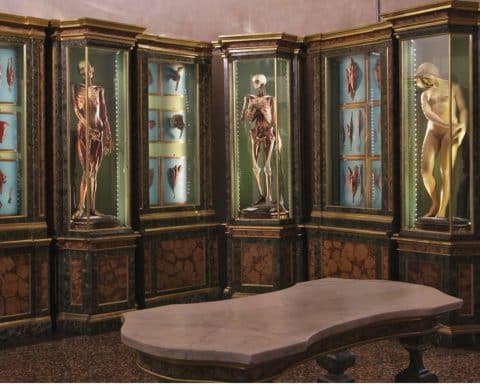

Meanwhile over in New York, once a week the anatomy lab becomes an art studio.13 Medical students have the option to participate in an 8-week module of artistic instruction and experimentation and in so doing process their feelings of death and dying, reaching a place of balance, the singularness of every human body. Running through the evaluations was a persistent theme; the creative act in the emotionally charged space of the anatomy lab brought about much needed catharsis.

Another fascinating intervention involving art-making has been pioneered at the University of Michigan.14 First-year medical students are paired with community volunteers with long-term conditions for a year-long project. A key part of this learning initiative is the ‘interpretative project’; an opportunity to give back to their volunteers through a creative, artistic act, acknowledging their deeper understanding of the volunteers’ experiences through their year-long association. The creative act has huge power, changing the process of reflection (often limited to feeling) to something more tangible, centred on action.

In the UK we can look to Bristol University Medical School, which has made humanities and art-making compulsory,15 robustly defending the idea of ‘compulsory creativity’ and its place in the over-stretched curriculum. Each student at Bristol produces an artwork as part of their humanities coursework — there is no assessment other than authentic engagement. The collected artwork, Out of Our Heads, is full of playful insight, intimate connection, and articulate rage.

St George’s Medical School has launched Open Spaces, an interdisciplinary project inviting students and staff at the hospital to participate in creative workshops in visual arts, sculpture, and photography, as well as dance, movement, and music. All are welcome and participants are encouraged to try out creative areas they are unfamiliar with.

In these many ways art-making can encourage clinicians to ‘make strange’ and challenge the algorithm, disrupt automatic thinking, and deliver truly holistic care.16 Art-making disrupts the commonplace, it emphasises yet undermines pattern-seeking. Art-making plays with the subjective, the ambiguous. It shows a way to synthesise the technical with the humane, to innovate.

I end with my own offering on the value of art-making. The evaluations of our lockdown activity found that it was enjoyable, stimulating, relaxing, and promoted team bonding and self-reflection.

Amid the stress and isolation of the pandemic it proved a hugely important activity. Whether or not it can be measured, or even defined, creativity is essential to medical practice. Because creative doctors are engaged doctors.

References

1. Snow CP. The Rede lecture, 1959. In: The Two Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993; 1–52.

2. Snow CP. Human care. JAMA 1973; 225(6): 617–621.

3. Reilly JM, Ring J, Duke L. Visual thinking strategies: a new role for art in medical education. Fam Med 2005; 37(4): 250–252.

4. Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23(7): 991–997.

5. Alkhaifi M, Clayton A, Kangasjarvi E, et al. Visual art-based training in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach 2022; 44(5): 500–509.

6. Mukunda N, Moghbeli N, Rizzo A, et al. Visual art instruction in medical education: a narrative review. Med Educ Online 2019; 24(1): 1558657.

7. Kidd MG, Connor JTH. Striving to do good things: teaching humanities in Canadian medical schools. J Med Humanit 2008; 29(1): 45–54.

8. Shapiro J, Coulehan J, Wear D, Montello M. Medical humanities and their discontents: definitions, critiques, and implications. Acad Med 2009; 84(2): 192–198.

9. Courneya CA. Illustrating the art of (teaching) medicine. Cogent Arts & Humanities 2017; 4(1): 1335960.

10. Green MJ. Comics and medicine: peering into the process of professional identity formation. Acad Med 2015; 90(6): 774–779.

11. Maatman TC, Minshew LM, Braun MT. Increase in sharing of stressful situations by medical trainees through drawing comics. J Med Humanit 2022; 43(3): 467–473.

12. Shapiro J, McMullin J, Miotto G, et al. Medical students’ creation of original poetry, comics, and masks to explore professional identity formation. J Med Humanit 2021; 42(4): 603–625.

13. Grogan K, Ferguson L. Cutting deep: the transformative power of art in the anatomy lab. J Med Humanit 2018; 39(4): 417–430.

14. Kumagai AK. Perspective: acts of interpretation: a philosophical approach to using creative arts in medical education. Acad Med 2012; 87(8): 1138–1144.

15. Thompson T, Lamont-Robinson C, Younie L. ‘Compulsory creativity’: rationales, recipes, and results in the placement of mandatory creative endeavour in a medical undergraduate curriculum. Med Educ Online 2010; 15(1): 5394.

16. Viney W, Callard F, Woods A. Critical medical humanities: embracing entanglement, taking risks. Med Humanit 2015; 41(1): 2–7.

Featured image by Vincent van Zalinge on Unsplash.