Paul McNamara is a GP in Glasgow and Honorary Clinical Lecturer at the University of Glasgow

Katie Collins is a 4th year medical student at the University of Glasgow

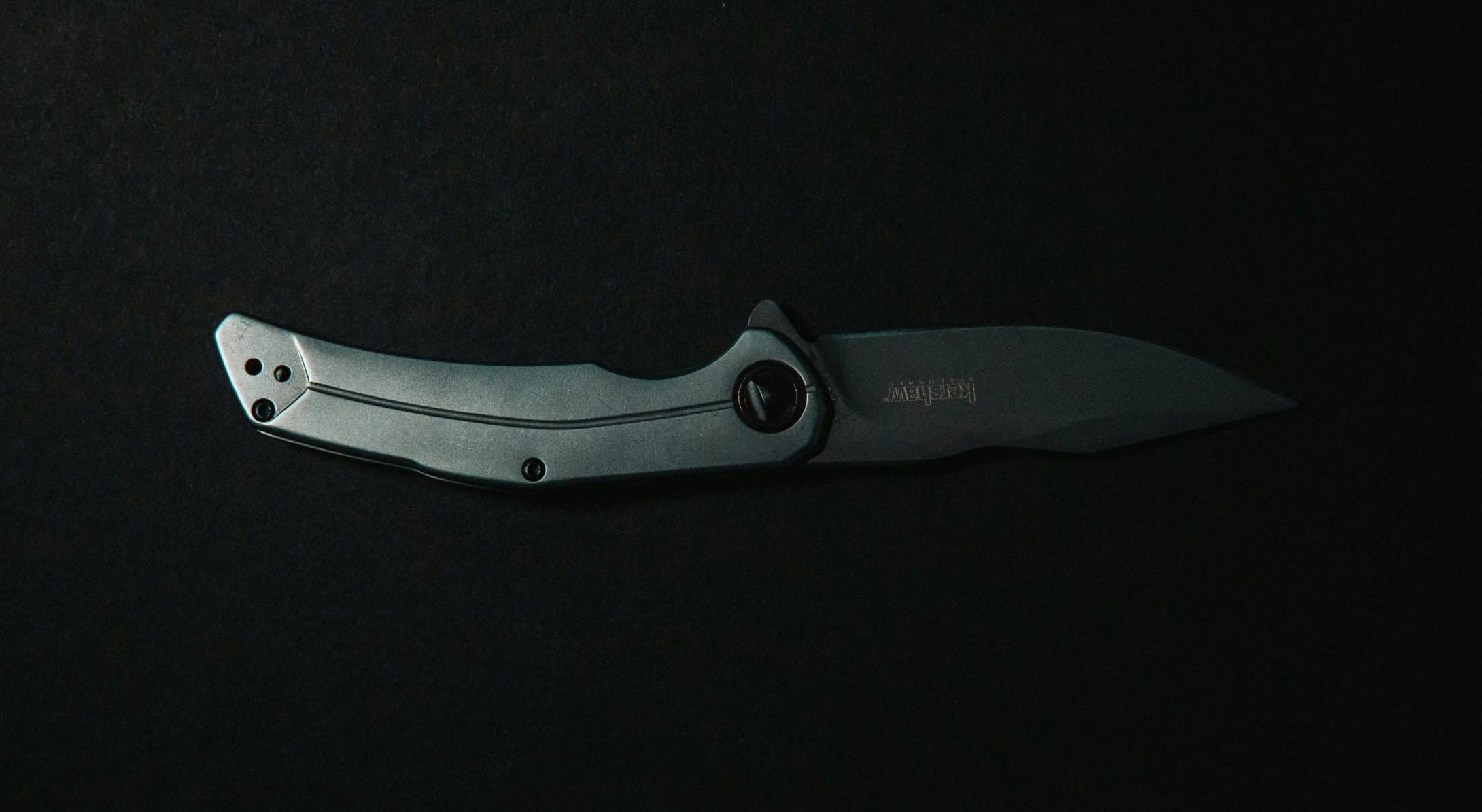

In May 2025, 16-year-old Kaden Moy was fatally stabbed at Irvine Beach.1 Just one day earlier in Edinburgh, a 17-year-old boy was left critically injured in a similar attack.2 Two knife-related incidents within 48 hours – both involving teenage boys. In the two months leading up to Kaden’s death, there had already been another fatality and at least 11 knife-related injuries involving young people.3 An outbreak of violence is spreading across Scotland – not linked to gangs or organised crime. This time, the offenders are children.

Once labelled the “Murder capital of Europe,” Scotland is no stranger to violent crime.4 In 2004-05 alone, the country recorded 137 homicides – 40 of them in Glasgow.5,6 The majority were knife attacks, often fuelled by alcohol, drugs, and gang rivalries. At this time, The United Nations went so far as to call Scotland “the most violent country in the developed world.”4

But something changed.

An outbreak of violence is spreading across Scotland – not linked to gangs or organised crime. This time, the offenders are children.

That same year marked the establishment of the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU), which introduced a new public health approach to tackling violence. Instead of viewing knife crime solely as a policing issue, the VRU appeached violence as a disease – one that could be identified, treated, and prevented.

Building on this foundation, Glasgow doctors launched Medics Against Violence in 2008, a charity that partnered with schools and universities to deliver education on violence prevention through real-life stories and early intervention. Alongside this came the A&E Navigator Programme, using trained support workers in emergency departments to engage with vulnerable patients at critical moments. These initiatives had a substantial impact. By 2024, the number of homicides in Scotland had fallen to 57, while knife-related assaults had dropped by nearly 70% compared to 2008.6,7

In recent years, however, a troubling trend has emerged – those involved in knife crime are getting younger. According to the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit, knife possession among 11- to 15-year-olds has risen by 15% over the past five years.8 Additionally, Police Scotland report a staggering 600% increase in serious assaults committed by teenagers in the same timeframe.9

So, what is driving this new wave?

Poverty and deprivation will always remain contributing factors. But today’s youth are also struggling with a growing mental health crisis. According to the 2022 Scottish Census, 15.4% of people aged 16-24 reported suffering from a mental health condition – a sixfold increase from just 2.5% in 2011.10 While headlines report CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) waiting times have improved, these figures exclude the thousands waiting for neurodevelopmental assessments for conditions such as ADHD and autism. In spring 2024, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde alone had 7,560 children still awaiting assessment.11

Progress has also been hindered by a lack of adequate funding. Since a commitment was made in 2021, only one Scottish health board has met the target of investing at least 1% of its budget into CAMHS.12Simultaneously, cuts have been made to youth services – YouthLink Scotland reports a 50% reduction in local authority youth workers over the past eight years.13

When young people cannot access timely mental health care or support services, their vulnerability increases. Many are left isolated, overwhelmed, and more likely to engage in risky behaviours such as substance misuse and violence. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, disrupting education, encouraging isolation, and fuelling anxiety. Social media has compounded the problem, offering a relentless cycle of comparison, online bullying, and exposure to violence. Add to this a heightened awareness of global instability – climate change, war, job insecurity – and the pressure on young people becomes unbearable.

So, what can be done?

Scotland must urgently invest in mental health services, youth programs, and community resources… Failure to act now risks more young lives.

The most effective solution remains what we already know works: early intervention and prevention. Scotland already has strong foundations in place – programmes like the Violence Reduction Unit, Medics Against Violence and the hospital navigator programme. These have made real progress in addressing the root causes of youth violence. Expanding and properly funding these initiatives could significantly reduce the involvement of young people.

Diversionary activities are important. More options for engagement in sports and mentoring programmes can help steer young people away from antisocial behaviour and towards building positive relationships and essential life skills. However, these efforts must be supported by investment into community youth centres and well-resourced schools. Additionally, investment in accessible and timely mental health services is essential to support young people throughout their education – helping them stay engaged in learning, reduce behavioural issues, and avoid risk-taking behaviour.

Knife-related youth violence in Scotland has become an urgent crisis, driven by worsening mental health, lack of support, and growing uncertainty in an unstable world. Despite past progress in reducing violence, today’s youth face serious consequences without timely intervention. To stop this surge, Scotland must urgently invest in mental health services, youth programs, and community resources – while maintaining a just balance between rehabilitation and accountability in the justice system. Failure to act now risks more young lives.

Duty editor’s note – on a related topic see: https://bjgplife.com/netflixs-adolescence-an-unsettling-reminder-of-the-toxic-effect-of-social-media-on-children/

References

- Police Scotland. Operation Redolence – Death of Kayden Moy [Internet]. Scotland: Police Scotland; 2025 [updated 2025 May; cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://mipp.police.uk/operation/SCOT25S22-PO1

- Teenager in hospital after being ‘stabbed’ at Portobello Beach [Internet]. Edinburgh: STV News; 2025 May 17 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://news.stv.tv/east-central/teenager-in-hospital-after-being-stabbed-at-portobello-beach

- Two teens dead and eleven injured in spate of youth knife incidents across Scotland [Internet]. Edinburgh: STV News; 2025 May 20 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://news.stv.tv/west-central/two-teens-dead-and-eleven-injured-in-spate-of-youth-knife-incidents-across-scotland

- Medics Against Violence. Scotland’s shameful history with violence [Internet]. Glasgow: Medics Against Violence; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.mav.scot/topic/scotlands-shameful-history-with-violence/

- BBC News. Sturgeon says knife crime is a “national emergency” [Internet]. 2005 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/4527570.stm

- BBC News. Homicides in Scotland up 10% but still at historic low [Internet]. 2024 Oct 29 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c80lv23ng43o

- Scottish Parliament. Official Report: Meeting of the Parliament, Thursday 22 May 2025 [Internet]. Edinburgh: Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.parliament.scot/api/sitecore/CustomMedia/OfficialReport?meetingId=16433

- Police chief appeals to young people not to carry knives [Internet]. Edinburgh: BBC News; 2025 May 20 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cn8zzz112e3o

- Swinney accused of being ‘weak’ on knife crime amid spate of youth violence. STV News. May 22, 2025. Available from: https://news.stv.tv/scotland/first-minister-john-swinney-accused-of-being-weak-on-knife-crime-amid-spate-of-youth-violence

- National Records of Scotland. Scotland’s Census 2022: Health, disability and unpaid care [Internet]. Edinburgh: National Records of Scotland; 2024 Oct 3 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/2022-results/scotland-s-census-2022-health-disability-and-unpaid-care/

- Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland. Thousands of children and young people on “hidden” ADHD and autism waiting lists in Scotland [Internet]. Edinburgh: Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland; 2025 Apr 14 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2025/04/14/thousands-of-children-and-young-people-on–hidden–adhd-and-autism-waiting-lists-in-scotland

- Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland. Briefing on funding for mental health services: response to Scottish Budget for 2025–26 [Internet]. Edinburgh: Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland; 2025 Jan [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/members/devolved-nations/rcpsych-in-scotland/policy/policy-updates/rcpsychis—budget-response-briefing—final.pdf?Status=Master&sfvrsn=c9139976_5

- Youth Scotland. Campaign to save youth work services as figures reveal millions in cuts [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.youthscotland.org.uk/news-article/campaign-to-save-youth-work-services-as-figures-reveal-millions-in-cuts/

Featured Photo by Jason Jarrach on Unsplash