Jordi Amblas (right) is a geriatrician and Chair of Palliative Care in the Faculty of Medicine, Central University of Catalonia, Spain.

The introduction of early palliative care might be hoped to moderate the medicalisation of dying and the increasingly frequent medical and surgical treatment that patients generally receive in the last months of life.

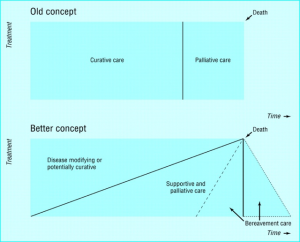

Indeed the old concept of an abrupt change from curative to palliative care when a person is terminally ill and imminently dying is giving way gradually to the better concept of a phased introduction of palliative care from diagnosis of a life-threatening illness as advocated in Fig 1.1

By 2018 general practitioners in Scotland recognised 69% of their patients for a palliative care approach by the time they died, calling it “anticipatory care”. This “ primary palliative care” was associated with more frequent care planning, more patients dying in their place of choice and less hospital admissions.2

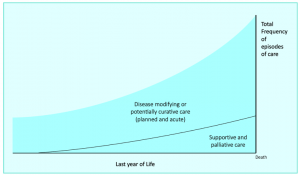

While integrated palliative care delivery is gradually increasing throughout the last year of life, disease modifying and potentially curative care and unplanned care is not decreasing.

Ninety-five percent of patients in their last year of life receive emergency and unscheduled care.3 Planned primary and hospital care for disease management also rise steeply in the last trimester in England and Canada.4,5

Figure 2 illustrates this by plotting the monthly frequency of medical service episodes which patients receive in their last year of life. This reveals the great increase in the number of episodes of “curative” care as death approaches. This is hidden in figure 1 which only shows the increasing percentage of people receiving a palliative care approach.

So palliative care is reaching more people with cancer, organ failure and frailty and dementia, and starting earlier, but planned and emergency medical care continues to expand even more both in hospitals and in primary care.

Why is this? Who is responsible for this, and whose job is it to address this issue? Palliative care specialists bemoan that their specialty is stigmatised, and referrals come late if at all. But they never consider they have a public health duty to address this issue of overzealous treatment of the population who are dying.

Is it patients demanding more treatments than might be wise, hoping against hope for a cure? Is it hospital doctors doing what they can do and know how to do, rather than should do? Is it lack of effective care planning and communication between all settings? Is it the decrease in continuity of care, especially out-of-hours?

Compared to countries where curative care is not available to some patients at all due to lack of resources, inappropriate and sometimes very costly care is especially wrong and inequitable.

The deep-seated over medicalisation of death must be addressed.

Much such care in retrospect is clearly futile, and quality indicators for appropriate and inappropriate end-of-life care in people with Alzheimer’s disease, cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary have been identified to assess this further.7 Low-value high-cost care can cause much suffering. An early palliative approach can prevent or ameliorate suffering and must be an informed option and available for all. Primary care may be best placed to take this forward.

References

- Murray SSA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007.

- Finucane AM, Davydaitis D, Horseman Z, et al. Electronic care coordination systems for people with advanced progressive illness: a mixed-methods evaluation in Scottish primary care Br J Gen Pract 2020;70(690):e20–8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X707117.

- Mason B, Kerssens JJ, Stoddart A, et al. Unscheduled and out-of-hours care for people in their last year of life: a retrospective cohort analysis of national datasets. BMJ Open 2020 Nov 23;10(11):e041888. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041888.

- Diernberger K, Luta X, Bowden J, et al. Healthcare use and costs in the last year of life: a national population data linkage study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021 Feb 12:bmjspcare-2020-002708. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002708.

- Michelle Howard, Abe Hafid, Sarina R. et al. Intensity of outpatient physician care in the last year of life: a population-based retrospective descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2021 Jun 4;9(2):E613-E622. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210039. Print Apr-Jun 2021.

- World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care nd symptom relief into primary health care: A WHO guide for planners, implementers and managers. 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/integrating-palliative-care-and-symptom-relief-into-primary-health-care

- De Schreye R, Houttekier D, Deliens L, Cohen J. Developing indicators of appropriate and inappropriate end-of-life care in people with Alzheimer’s disease, cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for population-level administrative databases: A RAND/UCLA appropriateness study. Palliat Med 2017 Dec;31(10):932-945. doi: 10.1177/0269216317705099.

Featured photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash