Nada Khan is an Exeter-based GP and clinical academic, and an Associate Editor at the BJGP.

Nada Khan is an Exeter-based GP and clinical academic, and an Associate Editor at the BJGP.

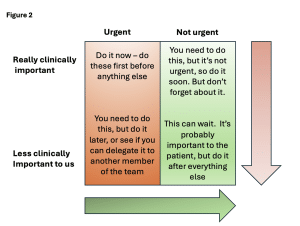

I think I learned about it during a training session on time management, but since then, I’ve always used some kind of mental mapping of the Eisenhower Matrix to try and prioritise tasks. The Eisenhower matrix is an eponymous task management tool attributed to the late US President which helps to organise and prioritise tasks by urgency and importance, so you can focus on getting the most urgent and important things done first. The matrix takes the shape of a 2×2 quadrant (see figure 1) with jobs tagged as either urgent or not urgent, and important or not important. The system works recommends that you do the urgent and important jobs now, do the not urgent but important jobs later, make someone else do the urgent but not important jobs, and chuck out the not urgent and not important jobs. What’s the place of prioritisation models like the Eisenhower matrix in clinical practice, and how does this fit in with expectations from our patients and the wider practice team?

GPs are busy dealing with increasing patient complexity and increasing workload. This workload includes not just clinical contacts, but the not-so hidden administrative and interruptive work that often extends a clinical session.1 When faced with a (literally) never-ending list of tasks that seem to be multiplying in number like gremlins whilst you are working through them, something like the Eisenhower matrix could, in theory, help prioritise which tasks to work through first. Yes, send the two-week wait referral today (urgent and important) but that referral to physiotherapy for someone who has been experiencing knee pain for 8 months? That can wait, surely (important but not urgent). But is any task really ‘not important’? From our perspective, perhaps, but probably not from the patient’s perspective. And this is where a rigid interpretation of the Eisenhower matrix can fall down in practice, as the matrix suggests that there is one truth for how important or urgent a task is. Perhaps one for our colleagues with a critical realist ontological perspective to mull over.

GPs are busy dealing with increasing patient complexity and increasing workload. This workload includes not just clinical contacts, but the not-so hidden administrative and interruptive work that often extends a clinical session.1 When faced with a (literally) never-ending list of tasks that seem to be multiplying in number like gremlins whilst you are working through them, something like the Eisenhower matrix could, in theory, help prioritise which tasks to work through first. Yes, send the two-week wait referral today (urgent and important) but that referral to physiotherapy for someone who has been experiencing knee pain for 8 months? That can wait, surely (important but not urgent). But is any task really ‘not important’? From our perspective, perhaps, but probably not from the patient’s perspective. And this is where a rigid interpretation of the Eisenhower matrix can fall down in practice, as the matrix suggests that there is one truth for how important or urgent a task is. Perhaps one for our colleagues with a critical realist ontological perspective to mull over.

But is any task really ‘not important’? From our perspective, perhaps, but probably not from the patient’s perspective.

The urgent and important jobs are generally easy to recognise for GPs, practice staff and patients. These tasks keep us occupied because they come in frenzied requests, and before we know it, our time can be spent. These tasks are unpredictable in general practice and can be highly interruptive. The crash alarm going off, the patient needing hospital admission, or urgent end of life care medication requests. We rightly need to make these a priority.

We can spend a lot of time stuck working on the urgent but not important (to us) tasks. Tasks in this quadrant are tricky because they present under the guise of an important task based on the perspective of the person setting it. These jobs might come through as same day requests for private referrals, or non-urgent medication requests. Patients may request these as urgent, and practice staff might also be working to their own internalised Eisenhower matrices, or are influenced by a sense of urgency transferred from patients. These jobs can quickly form the bulk of the GP administrative workload, and although ticking these tasks off may make you feel like you’re achieving something, these jobs are really just distracting you from more important things you could be focussing on.

The risk of the not urgent but important tasks is that we might not find a time to do them later. These tasks are important to us but can often get side-lined with more urgent requests because nobody else sees these jobs as important to them. For instance, you need to find a time to look through the rota to book a week of annual leave. You don’t have to do it right now, but the longer you leave it, the more perilous finishing this task becomes, especially with continuous interruptions with those urgent but not important jobs.

The not important, not urgent tasks – well, the Eisenhower matrix delegates this to the bin, almost literally, suggesting that these tasks should be eliminated as they are not important or urgent. To optimise time management, you’re supposed to ignore or bin these tasks as they are just wasting your time, but in general practice, how should these be managed? This is where the matter of perspective counts and where I’m starting to struggle a bit with the Eisenhower matrix. That job that I think isn’t important or urgent might be very important to a patient, or feel very urgent to a receptionist who is dealing with a worried patient at the front desk. Binning tasks or patient requests often isn’t a viable option in general practice.

So, am I throwing the Eisenhower matrix out the window?

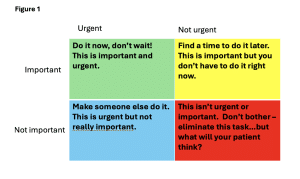

What I’m taking away from this is that most things are important to patients, so there’s not much of a place for a ‘not important’ box, but perhaps a ‘less important for right now’ gradient. And the not urgent and not important quadrant and Eisenhower’s advice to eliminate the task altogether? I don’t think most patients would be happy to know that these requests are being ‘eliminated’, but this might be where Stott and Davis’ consultation model, another infamous 2×2 quadrant, might come into play. If patients are presenting with not clinically important and not urgent issues, this is an opportunity to modify that non-urgent and non-important help-seeking behaviour. This might sound tedious, but this approach aims to instil long-term resource management (education about the natural history of illness, self-help or use of the pharmacy and over the counter remedies) and better use of the practice appointment and task system.2

So, am I throwing the Eisenhower matrix out the window? Not exactly, but I am moving towards more of an Eisenhower ‘gradient’ (Figure 2). The really clinically important and urgent things need fairly urgent prioritisation, but the urgent and less clinically important things can be done later. And I’ve started to set a dedicated time, often first thing in the morning before I get interrupted with urgent tasks, to do the important things that can often get side-lined. I don’t think there’s a place for a strategy of eliminating fully the non-urgent and not-important tasks, but this is an opportunity to explore why these tasks are urgent and important to others, and perhaps for changing perspectives both ways.

References

- Sinnott C, Moxey JM, Marjanovic S, Leach B, Hocking L, Ball S, et al. Identifying how GPs spend their time and the obstacles they face: a mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(715):e148-e60.

- Stott NC, Davis RH. The exceptional potential in each primary care consultation. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1979;29(201):201-5.

Featured photo by Austrian National Library on Unsplash