Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

If it is difficult to agree what exactly we mean by health, it is perhaps unsurprising that we also approach unhealth in a number of different ways. In both cases, we look sometimes at what is only visible through a microscope, sometimes at the patient’s experience, and sometimes at other things again. In the many current and past examples of divergent behaviour, ability, or identity which have fallen under the medical gaze, we examine society’s attitude to a person, and the various restrictions, freedoms and obligations which this confers on them. The spectrum of unhealth therefore stretches from the scientifically concrete, a bacillus of Mycobacterium leprae stained red on a microscope slide, to the socially metaphorical, a leper exiled from their former life and separated by water from family and friends.1

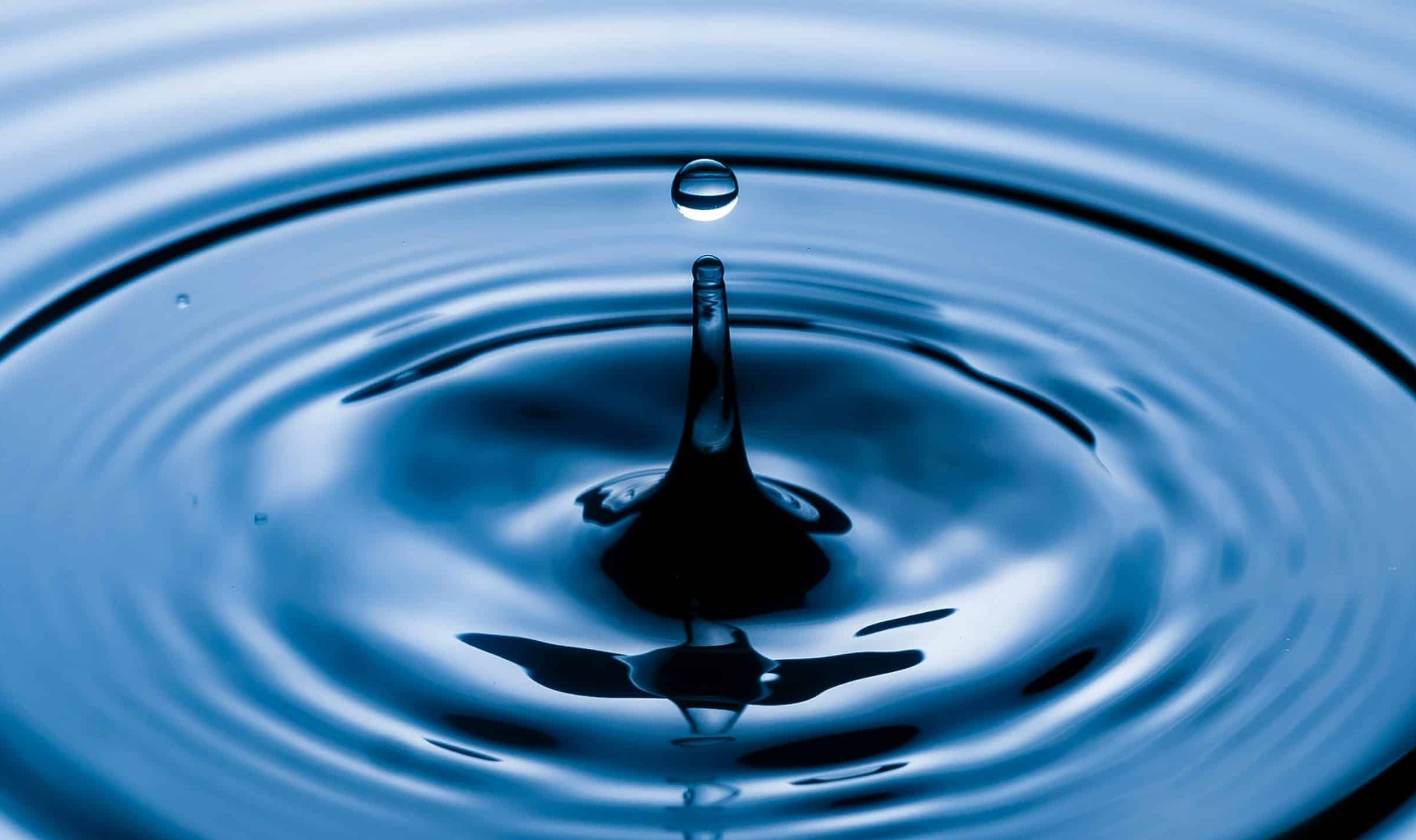

Disease is like a stone dropped into the pond of someone’s life, and illness and sickness are the concentric ripples that affect them personally and in their wider interactions with people around them.

We can think about how these things fit together. Disease is like a stone dropped into the pond of someone’s life, and illness and sickness are the concentric ripples that affect them personally and in their wider interactions with people around them.2,3 We might add another, burden, reflecting the impact of their condition on the smooth running of the health service. Patients and doctors generally find it easiest to talk about disease, the most easily grasped, and a convenient synecdoche that includes the others. Dealing with a disease generally addresses the corresponding illness, sickness and burden, in which case it isn’t really necessary to distinguish between them.

There are other circumstances, though, in which this is less clearly so. It is possible to have a disease identified at an early stage without any corresponding illness, although it may still cause sickness if treatment or monitoring necessitate time off work, as well as a certain burden. Illness without disease can be hugely problematic for patients, who know there’s something wrong and understandably seek the validation of a clear cause, and for doctors, who try to take hold of a solid diagnosis, only to feel it slip through their fingers like fine mud at the bottom of the pond. Sickness can exist in isolation too: someone may be legitimately signed off work because of circumstances there which make their job impossible, with no corresponding illness or disease outside of this unhealthy situation, and the NHS carries no burden as a result. Similarly, most patients taking cholesterol-lowering medication for primary prevention are neither diseased, nor ill, nor sick, although they have been identified as potentially burdensome, a risk to the system which must be mitigated. In each of these cases, we are dealing with ripples on a pond which overlap to a greater or lesser extent, and sometimes not at all; they are certainly not concentric, and can no longer be assumed to have a simple causal relationship with each other.

There is a hierarchy in unhealth too, in which the objectively verifiable ranks above the subjective, just as psychological conditions come below physical ones.

There is a hierarchy in unhealth too, in which the objectively verifiable ranks above the subjective, just as psychological conditions come below physical ones. In this context, disease connotes genuineness: however real someone’s illness, there is still on both sides of the consultation a preference for framing it in ways that feel unambiguous.4 We can see this bias reproduced in screening programmes, which aim to uncouple the cure of disease from the treatment of illness, the tidy from the messy.

Our first thought in any consultation is to observe the ripples on a patient’s pond in order to reach into the water and find a stone, and this works often enough that when our first attempts fail, we usually just try harder. Ripples can also be caused by a passing breeze, though, or by the normal activity of fish; they may even be due entirely to our own efforts as we grope around for stones on the bottom. The reality is that ponds are not sterile containers of water patiently waiting for someone to lob stones into them, and nor for most people is life a straightforward business interrupted only by disease. In order to interpret a pattern of disturbances on the surface of either medium, we need to have a better understanding of the medium itself and the whole range of ways in which it is disturbed. In truth, we stand at the edge of an ocean rather than a pond, and if we think only in terms of treating diseases, and simply extend into the deeper water the techniques that work well in the shallows, we will drown. And yet, the deeps are where the majority of life takes place, and where patients find themselves in difficulties most often.

Just as it is reasonable to conceive of health differently in different contexts, it is essential if we are to help our patients that we also recognise and address the corresponding modes of unhealth. When there is a clear disease, it requires little imagination to treat it. When we are confronted with illness, however, we must also be able to see the individual; with sickness, the social context; and with burden, how the individual relates to the system. Health is regularly diminished by many things and in many ways, and our approach as doctors should reflect this. We all reach instinctively for the microscope or the phlebotomy needle, but if we can distinguish more clearly the context in which people who are unwell consult us, we may find ourselves in a position to do less and achieve more.

References

- Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag, first ed Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1978

- Cecil Helman, Disease versus Illness in general practice, Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1981, 31, 548-552

- Marshall Marinker, Why make people patients? Journal of Medical Ethics, 1975, I, 81-84

- Contested Illness in Context: an interdisciplinary study in disease definition, Harry Quinn Schone, Routledge, 2019

Featured photo by Omar Gattis on Unsplash