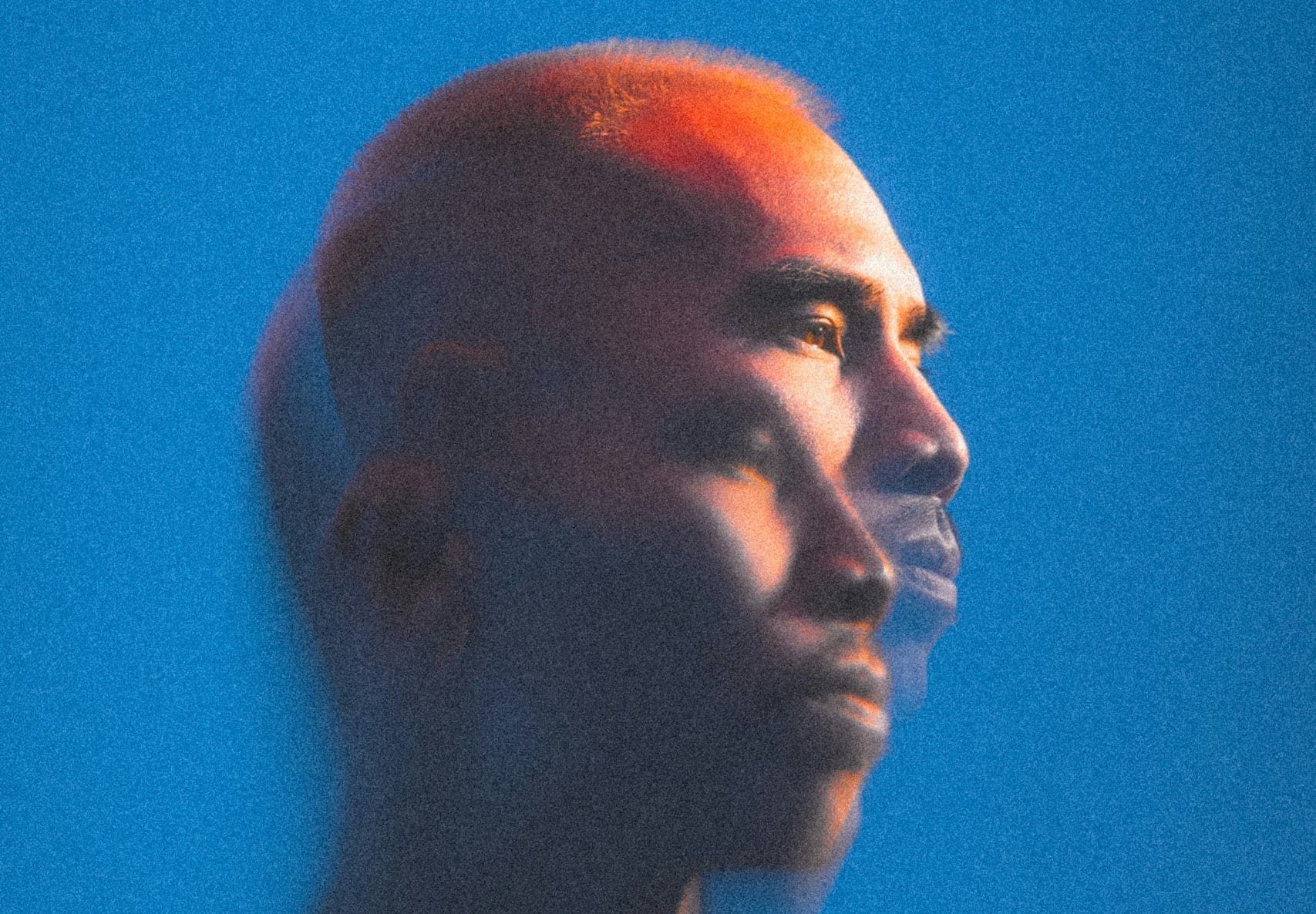

When you see a patient, you see double.

One person speaks. They sit in front of you, describe problems, answer questions. Their story moulded into symptoms and timeframes and offered in a form medicine recognises.

Alongside them is another person, invisible and nameless. This is the person shaped by fear, experience, and memory; by what they have learned it is safe to say, and what it costs to say more. They may be carrying grief, shame, exhaustion, anger, or loneliness. This second person is often silent but never absent.

This is the person shaped by fear, experience, and memory; by what they have learned it is safe to say, and what it costs to say more.

In the rush of the consultation, it is easy to forget this doubling.

Often, life in general practice is framed by time. Ten-minute slots exert its own pressure, narrowing our attention. We listen with one eye on the clock, already planning the next question, the next task, the next screen. We become expert at extracting what we need: red flags, timelines, differentials. Efficiency becomes a form of care. And often, it must be.

But something subtle is lost when we attend only to the spoken patient.

The unspoken person rarely announces themselves directly. They appear obliquely. They surface in the long pause after a question, in the minimising of distress, in sudden tears that seem disproportionate to the problem named. They are there when a patient says, “I know it’s probably nothing,” or “I don’t want to be a bother.”

The unspoken patient is not a separate person. They are the same individual, seen from another angle. Medicine with its guidelines and pathways gives us excellent tools for the first. The second requires something more nuanced: attention without urgency, curiosity without interrogation, permission without pressure.

This is not about turning every consultation into therapy. It is about remembering that what is said is shaped by what feels possible to say. Patients are constantly editing themselves in front of us, making rapid judgements: Is this doctor rushed? Are they interested? Will I be taken seriously?

We are making judgements too. Within seconds, we decide what kind of consultation this will be: straightforward or complex, easy or time-consuming. These decisions shape the space that follows.

Sometimes, simply acknowledging the second person is enough. A question that leaves room rather than closes it. A silence not immediately filled. A phrase such as, “Is there something else you were hoping we might talk about today?” Small invitations offered gently and without obligation.

Good general practice is not about uncovering everything, every time. It is about holding both people in mind—even when only one has a voice…

Good general practice is not about uncovering everything, every time. It is about holding both people in mind—even when only one has a voice—and practising in a way that leaves the door slightly open, should the other ever wish to step forward.

Continuity matters here. The unspoken patient often speaks slowly, over months rather than minutes. They reveal themselves in fragments and revisits. Trust accumulates quietly.

There will be days when the system intervenes —when the waiting room is brimming and the consultation must narrow simply to survive it. On those days, seeing double may feel like an impossible luxury. But even then, remembering that there is more beneath the surface is enough.

Seeing double does not slow practice but deepens it.

It reminds us that symptoms are rarely just symptoms, and that the consultation is not merely an exchange of information, but a meeting between two complex human beings.

In the end, seeing double is not about doing more. It is about noticing more: holding in mind both the story that is told and the one that waits, and practising medicine in a way that remains attentive, compassionate, and quietly present.

Featured photo: by Karsten Winegeart on Unsplash