Mohammad Sharif Razai is a National Institute for Health and Care Research Clinical Lecturer in Primary Care at the University of Cambridge, UK.

Mohammad Sharif Razai is a National Institute for Health and Care Research Clinical Lecturer in Primary Care at the University of Cambridge, UK.

Peer review remains central to maintaining quality and standards in scientific research. It can be described as ‘the process where experts from a specific field or discipline evaluate the quality of a peer’s research to assess the validity, quality and often the originality of articles for publication.’ 1 Despite its vital gatekeeping role in academic publishing, peer review itself has only recently become the subject of serious scrutiny, with growing efforts to guide its ethical practice.2 Less attention, however, has been paid to how the quality of peer review is defined and assured.3

Through peer review, the scientific community hopes to identify methodological flaws, detect ethical violations, provide constructive feedback, improve manuscript clarity, and ensure scientific integrity. This depends on the competence, expertise, motivations, and values of individual reviewers and often on chance. The system, however, has been critiqued for its opacity, inconsistency, lack of accountability, and potential for bias.4 The absence of standardised training, accreditation, sometimes vague reviewer guidelines, and a lack of feedback mechanisms often exacerbate these problems.5

“Publishers are charging authors and institutions substantial fees for open access while relying on unpaid peer reviewers to legitimise the process and outputs.”

Peer review continues to be a voluntary and often under-recognised form of academic labour, although some initiatives now aim to acknowledge and incentivise this work. For many, it represents yet another demand on already overstretched academic workloads. Moreover, peer review functions within a scholarly publishing ecosystem that many view as potentially exploitative. Publishers are charging authors and institutions substantial fees for open access while relying on unpaid peer reviewers to legitimise the process and outputs. This commercial model has drawn increasing criticism, particularly as the growth of predatory publishing further complicates the situation and places the system under strain.6

There is no agreed-on definition of high-quality peer review. However, the poor-quality peer review is often easier to recognise. Review reports may be cursory, vague, irrelevant, unconstructive, overly or insufficiently critical, or delayed.7 Some reviewers may fail to identify basic methodological and factual errors, or even make erroneous suggestions themselves. Many flawed studies receive superficial or inadequate peer reviews and are published, often driven by the pressures of high-volume output and rapid editorial turnaround. Some are later retracted or corrected, but others may continue to be cited and may influence practice despite their deficiencies.

Based on these characteristics, we can define quality in peer review as referring to the clarity, relevance, and accuracy of the feedback; its constructiveness and fairness; and the timeliness of its delivery, as well as the extent to which it contributes to the integrity and reliability of the scholarly work.

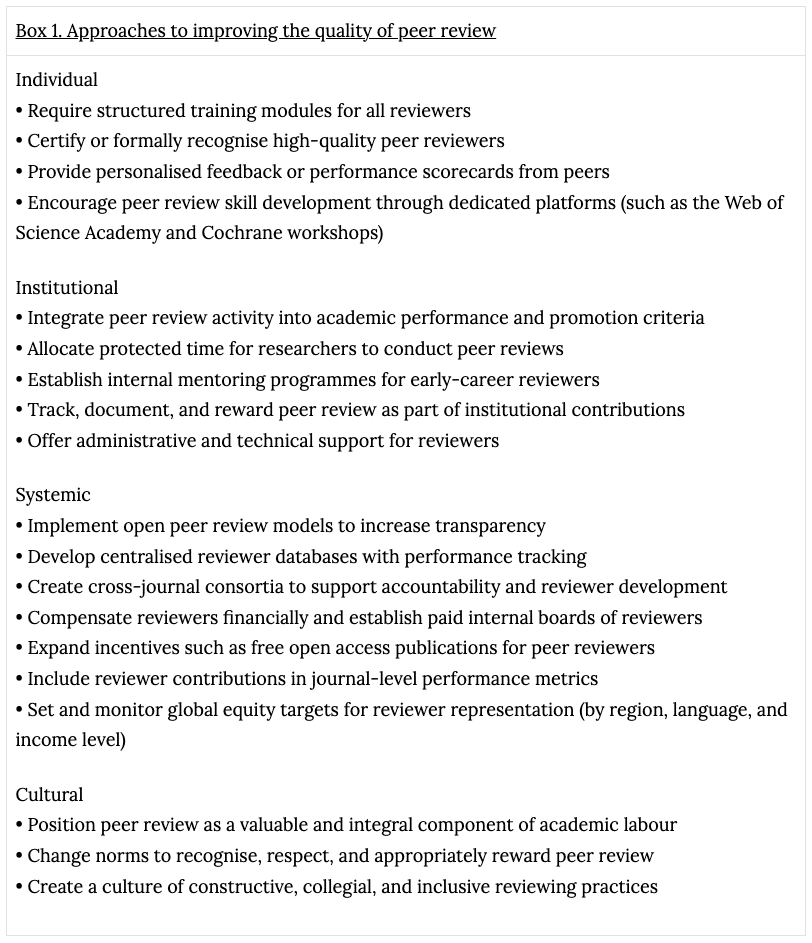

Efforts to improve peer review overlook the broader context in which reviewers operate. Some recommendations that could improve peer review quality could be organised into four levels of action: individual, institutional, systemic, and cultural (see Box 1).

Publishers need to be transparent about their financial models, generated profits, and motives, and take active steps to counter the perception of exploitative practices, thereby building trust and confidence among researchers. More importantly, they should remunerate peer reviewers appropriately for their time, expertise, and intellectual labour. Compensation should be fair, standardised, and transparent, acknowledging peer review as a skilled scholarly contribution rather than an invisible and unpaid service.

Peer review itself should be recognised as a scholarly output and part of the intellectual commons of science. High-quality reviews contribute to the rigour, ethics, and reliability of the academic record and have value beyond manuscript selection. With appropriate consent and safeguards in place, anonymised peer review reports could be made openly available for analysis, training, and scholarly study. Additionally, peer review could be developed as a field of inquiry and practice in its own right, with dedicated research.

Peer review underpins research and, given its central role in ensuring the integrity, legitimacy, and validity of scientific work, it demands watertight mechanisms for evaluating its own quality and effectiveness. Achieving consistently high standards needs commitment and coordinated investment across researchers, institutions, funders, and publishers. The peer review system must be held to the same standards of rigour that we expect from the science it is meant to uphold.

References

1. Wiley Author Services. What is peer review? https://authorservices.wiley.com/Reviewers/journal-reviewers/what-is-peer-review/index.html (accessed 7 Oct 2025).

2. Committee on Publication Ethics. Guidelines: ethical guidelines for peer reviewers. 2017. https://publicationethics.org/media/237/download?attachment (accessed 7 Oct 2025).

3. Tennant JP, Ross-Hellauer T. The limitations to our understanding of peer review. Res Integr Peer Rev 2020; 5: 6.

4. Proctor DM, Dada N, Serquiña A, Willett JLE. Problems with peer review shine a light on gaps in scientific training. mBio 2023; 14(3): e0318322.

5. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med 2006; 99(4): 178–182.

6. Grudniewicz A, Moher D, Cobey KD, et al. Predatory journals: no definition, no defence. Nature 2019; 576(7786): 210–212.

7. Hsu C-H. Dear editors, your publication delays are damaging our careers. Nature 2025; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-025-01072-5.

Featured photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash.