Ben Hoban lives and works in Exeter

Ben Hoban lives and works in Exeter

We talk about taking a history from a patient in the same way as taking blood: collecting a medium from which clinically useful information about the individual can be extracted. Histories – stories – are not just about individual people or events, though, but about the significance we attribute to them: the hero, the villain, the problem and the resolution. You and I may observe the same event but give different accounts based on our own understanding of what we’ve seen, influenced by how we felt, our past experiences and values. Establishing context and deciding which details to include in our story and how they are connected is an active process through which we make sense of our experience rather than simply registering it.1,2

We talk about taking a history from a patient in the same way as taking blood: collecting a medium from which clinically useful information about the individual can be extracted.

There are times, too, when the sense comes first, and the story establishes itself from the available elements. I may have a gut feeling that something is wrong, in which case you must be the villain, the others must be in on it, and I’d better do something about it right now.3 The facts here are secondary: our naked impression clothes itself with whatever is to hand. This is arguably the basis for cognitive distortions such as fundamental attribution error and confirmation bias:4 In a story, someone doing something bad must be the bad guy, and once the story starts to take shape, we can only assimilate new information in a way that fits the plot. The way to change the narrative in this situation is to alter the overall impression rather than the details.

Patients come to see is in primary care with an assortment of narrative components: context, facts, interpretation and impression, in various states of assembly. Our privilege in the consultation is to engage with these to build a story – however limited – that makes sense. The doctor listened. I have to stop driving because of what happened. It’s because I’ve been too busy with work to look after myself, but I know what to do now, and it should get better soon.

Conspiracy theories gain a following not because they are rational, but because they include these three elements: explanatory power, intention, and proportionality.

By assigning a role in the narrative to each fact or circumstance, an effective story connects how things were, how they are now, and how they might be in the future; the more elements it connects, the more compelling it seems. Likewise, a story in which things happen for a reason, and big things happen for big reasons, is inherently more believable. Conspiracy theories gain a following not because they are rational, but because they include these three elements: explanatory power, intention, and proportionality.5 The problem with a lot of what we tell patients is that, however true, it doesn’t feel very believable. A patient suffering from severe chronic back pain knows that there’s something seriously wrong and saying it’s just a mechanical problem won’t cut the mustard. A narrative approach would be to explain that the pain is caused by a disastrous cascade of events in the musculoskeletal and nervous systems; that the body is trying to protect itself but tragically making things worse; and no wonder it’s difficult to live with if every day is a struggle against our own body!

We tend to sift our patients’ histories for clinically usable information, grist for the diagnostic mill, and to regard the rest by default as chaff. This kind of reductionist approach, the product of our science-based medical education, generally works quite well. On the other hand, who hasn’t experienced the frustration of patients whose problems seem at odds with science and whose history seems to be all chaff and no wheat? Sometimes there is no hidden grain of truth to be revealed, but there is usually sense to be made of what a patient is telling us. We won’t always be able to find the answer, but we should always listen well and aim to tell a good, and effective, story.

References

- Narrative Based Medicine: Dialogue and Discourse in Clinical Practice, eds Trisha Greenhalgh and Brian Hurwitz, BMJ, 1998.

- Storytelling in Medicine, eds by Colin Robertson and Gareth Clegg, Routledge, 2016

- Lisa Feldman Barrett, How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain, Pan, 2017.

- Croskery P, The Importance of Cognitive Errors in Diagnosis and Strategies to Minimize Them, Academic Medicine 2003;78:775-780

- Suspicious Minds: Why we believe conspiracy theories, Rob Brotherton, Bloomsbury Sigma, 2015.

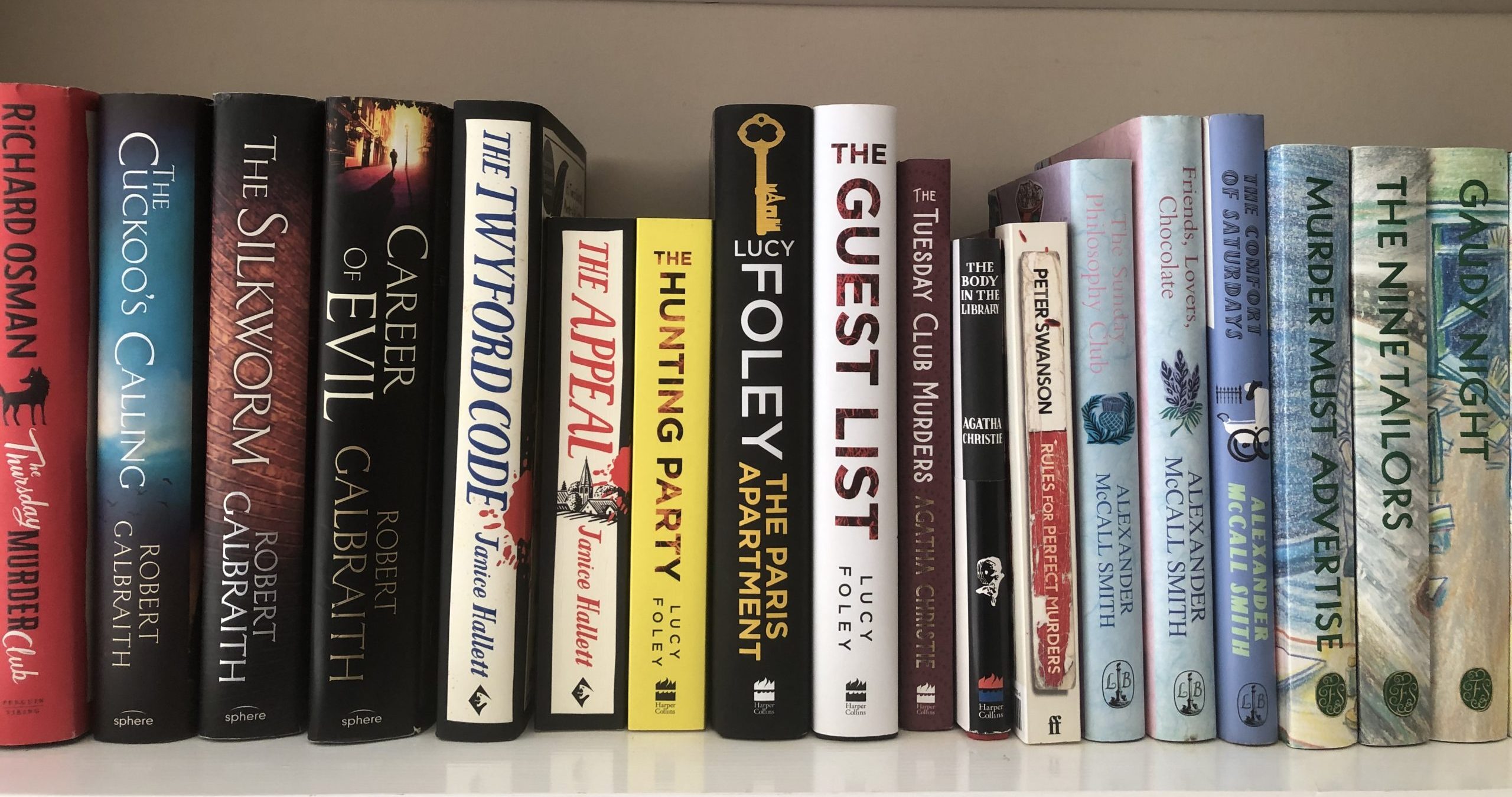

Featured image: Mystery novels on a shelf, photo taken by Andrew Papanikitas, 2022