John Launer is a retired GP and family therapist, now working as a medical educator and writer. He is on X: @johnlauner

John Launer is a retired GP and family therapist, now working as a medical educator and writer. He is on X: @johnlauner

One of the greatest English comic novels is The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, a Victorian stage comedian, and his artist brother, Weedon.1 The novel purports to be the diary of a middle-class city clerk, Charles Pooter, who recounts the surpassingly dull events of his everyday life in detail. Its status as a masterpiece (it has never been out of print since it was published in 1892) derives from the deadpan ordinariness of its fictitious narrator.

If I say that there are moments in Barbara Winton’s biography of her father, Sir Nicholas Winton2 — now made famous by the movie One Life with Anthony Hopkins — that reminded me of Charles Pooter, I mean this with absolutely no disrespect. I found the book compelling from start to finish, most especially because it records the life of someone who carried out one of the most heroic acts of the 20th century, but also emphasises what an utterly unexceptional life he led for the vast majority of his 106 years.

Apart from what he did for several months as a young man, it’s fair to say that Nicky Winton (as he liked to be called) would probably never have been commemorated apart from among his family and friends. He was a banker, then a stockbroker, and later a financial director of various small companies including an ice cream manufacturer. He lived for much of his life in Maidenhead, where he was a keen member of the rotary club but failed to be elected as a local Labour councillor.

He was often hard up. He was known for being pragmatic, but not particularly sensitive to other’s emotions or expressive of his own. He was married to a Danish woman he met after World War 2 and they had four children, one of whom died of meningitis as a child. He retired at 62 to work voluntarily for charities for the next four decades. He barely ever mentioned the heroism of his youth, until he was publicly ambushed by the TV presenter Esther Rantzen on a live TV programme 50 years after it happened, and subsequently honoured worldwide for his wartime actions.

Nearly all of his life was defiantly undramatic. Here are a couple of passages from his daughter’s biography of him, about the family home and his work:

‘On all sides were friendly neighbours. Next door an older couple, the Tanners, had a wonderful summer house in the garden, on a sort of rail that meant you could push it and turn it to face the other direction … Beyond them were a younger couple with young children also, the Skelts, who have remained friends to this day despite moving away from Maidenhead many years ago. Other neighbours were the Abreys, who remained in touch after we moved in 1958.’

‘Luckily, it was not long before he found something he thought would suit him: a relatively small company with an old friend at the head and with enough freedom in his role to suit him. A neighbour from our Altwood Bailey days, Mr Abrey, who ran a sheet metal company on the Slough Trading Estate, was looking for financial assistance at the time. He offered a job to Nicky, which he was glad to take.’

So why did I find every word of this sometimes Pooterish narrative not only gripping but deeply moving? Mainly because Barbara Winton wrote about her father not only with love and respect but also an absolute consciousness of what she was doing. To adapt the famous term by the philosopher Hannah Arendt when she wrote of the banality of evil, this book conveys what one might call the banality of heroism. For what Sir Nicholas Winton had once done was save the lives of 669 children, for whom he arranged air and rail journeys to the UK after the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939. One of the children he saved was my uncle, Zdenĕk Launer.

You’ll need to see the movie or read the book to learn fuller details — I cannot recommend either too highly — but the story is very simple. After cancelling a skiing holiday in order to visit Prague at the age of 29, Nicky Winton found it completely beyond belief that no-one was arranging for children from Jewish families there, or those with parents who were politically radical, to escape to the UK. Such schemes had already happened in Germany and Austria with the so-called Kindertransport. Together with a group of friends, Winton set up an office in a Prague hotel and invited families at risk to bring their children so they could record their details, addresses, and photos to try and arrange for their emigration.

With no other plans or resources apart from absolute conviction in what they were doing, his friends continued to add children to the list in Prague while Winton returned to London to establish a semi-fictitious organisation to seek placements for the children in homes in the UK. He advertised requests on behalf of individual children in the British press, and his group successfully arranged travel across Europe to bring them to their foster homes. Out of 5000 children on the list in Prague, Winton managed to find homes for around one in eight of them in 6 months. Almost all of those who were not placed were subsequently murdered by the Nazis along with their parents. Tragically, very few of the children Winton saved ever saw their own parents and families again.

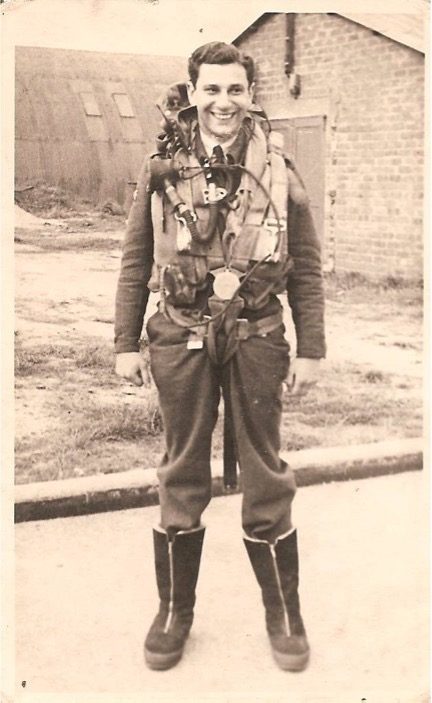

It was only a couple of years ago, when doing research for a family memoir,3 that I found my uncle Zdenĕk was one of ‘Nicky’s children’. (My father Bedřich was older and came over on a different scheme.) All I had known previously was that he managed to come from Prague at the age of 13 and stay with a family in Cardiff before later joining the Royal Air Force. I never knew him since he died in a plane crash just before the end of the war. But while seeing footage of the TV programme when dozens of the children, by then in their sixties or older, were reunited with their rescuer, I knew he would have wanted to be there. It’s consoling that at least 6000 people, counting children and grandchildren, are alive now because of Nicky Winton and his friends. It’s just as consoling to discover that Sir Nicholas Winton was an ordinary but determined man who one day just decided to be a Somebody.

References

1. Grossmith G, Grossmith W. The Diary of a Nobody. London: Penguin, 1999.

2. Winton B. One Life: The True Story of Sir Nicholas Winton. London: Robinson, 2024.

3. Launer J. Opening The Handbag Box: The Lives of Our Grandparents. London: John Launer, 2022.

Featured photo by Kingshuk Pal on Unsplash.