The consultation process between patient and doctor is a complex interplay of various factors, the ultimate aim being, simply put, problem resolution. The doctor and the patient form the core of the interaction with ideas, concerns and expectations being explored, modified, confronted and hopefully resulting in a harmonious agreement between the two parties. However, there is the obvious third component of the consultation; the presenting disease. Those who have practiced medicine long enough will know that a disease may not always be present. This, though, is not the starting point in most consultations where an inquisitive mind assumes the presence of disease and works to either prove or disprove its existence.

The way that disease presents varies; the most disconcerting aspect being how it may present differently to two physicians at two different times. As GPs, it is not unusual to face resistance from hospital doctors for a referral due to a lack of “hard” signs and symptoms, only for the original suspicions to be confirmed on hospital admission. Conversely, it is also not unusual to receive a somewhat disbelieving letter from casualty expressing amazement at how the GP could have missed the most obvious of conditions.

The reasons for such variation are not due to the patient and usually not due to the doctor. The doctor and the patient both have the ultimate aim of identifying what the underlying condition is; the patient is the crime scene with all the clues whereas the doctor is the detective trying to solve the puzzle.

What a good detective cannot control is a changing crime scene. Unlike a crime scene, the disease is constantly changing, affecting different parameters in the host, eliciting different symptoms and projecting different signs. The detective is left to solve the case in the ten minutes or so which he has with this ever evolving crime scene. Occasionally the crime scene will regurgitate all the clues up in a few minutes making the case clear as day. On other occasions it may take months or years for the clues to fall in place to allow the crime to be solved. It is the therefore the crime i.e. the disease that is the evolving factor in the triad of actors and hence the most important aspect of the consultation.

The doctor is the detective trying to solve the puzzle….. Unlike a crime scene, the disease is constantly changing

Not many would argue against the most likely diagnosis being a myocardial infarction (MI). This classical presentation of an MI is the most commonly taught in medical textbooks but is often irrelevant in General Practice. Many primary care physicians will have diagnosed MIs but few will have presented in this fashion. In my years of practicing, I have not seen an MI present in this way in the community. In actual fact, if all MIs did present this way it would make life a lot easier. The following is perhaps a more common presentation in primary care.

A 68 year old non-smoker, with a strong family history of ischaemic heart disease, complains of feeling tired for the last three days. He has been having a feeling of indigestion and bloating in the epigastric area for the same period of time. He feels tight in his upper abdomen. He doesn’t feel short of breath but increased activity makes him feel nauseous. He has been taking over the counter indigestion medication to little avail. Examination is unremarkable and he looks well whilst seated in the surgery. He is prescribed a course of proton pump inhibitors and asked to have a precautionary electrocardiogram (ECG) later that morning along with some blood tests. The hospital laboratory calls later in the afternoon to inform you that the patient has a troponin level 10 times above the normal.

The late afternoon scramble that generally ensues is not likely to be too unfamiliar to many general practitioners.

In another scenario the 68 year old may present to casualty an hour after seeing the GP, in the same manner as the 74 year old in the first scenario. He may feel aggrieved that he only saw his GP an hour ago who was unable to diagnose him correctly. Unfortunately, in my experience, it is not too uncommon for the casualty doctor sympathizing with the patient, ignoring basic dynamics in how disease may present in primary care.

The following cases* are based on actual presentations that I have been involved with over the years. I hope that they will help to understand this convoluted presentation of disease in a different way.

Case 1

A middle aged woman has been seeing her GP for approximately 10 years for joint pains. Blood tests organized to rule out inflammatory disease were normal. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia was made, particularly since her symptoms became worse after the sudden death of her husband and the ensuing depression. A few years after the initial presentation, she develops swollen joints and pain again and has another battery of blood tests which are negative. She is referred to the rheumatologist who eventually confirms the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Regular visits to the GP continue and in the 10th year of her initial presentation rheumatoid arthritis is eventually diagnosed after the synovial swelling returns, coupled by a positive rheumatoid factor. DMARD’s are started and all her symptoms resolve.

Case 2

A man in his 70s attends with a three day history of cough, wheeze, mild amounts of productive mucous and mild shortness of breath. He has never smoked. He complains of feeling hot and cold. A chest infection is diagnosed based on examination findings and the suggestive history. A course of antibiotics is prescribed. He returns 2 weeks later feeling slightly better but breathing still not having returned to normal and still having a fair bit of cough. He is noted to be well without any obvious shortness of breath and a second course of antibiotics is prescribed on the assumption of an unresolved infection. He returns 2 weeks later not feeling fully back to normal and still having mild shortness of breath. On full examination a mildly tender left calf is noted. Blood oxygen saturation is at 96%. He is referred to hospital and eventually diagnosed with bilateral pleural emboli.

Case 3

An elderly woman was seen during a home visit with 24 hours of left buttock pain. She had been involved in some celebrations the day before but this felt slightly different from her usual musculoskeletal pain. She is found well, fully mobile and comfortable in the house. No restriction in movement is noted. All her observations are normal and she provides a urine sample, due to a past history of renal colic, which is normal. Abdominal examination is performed as she feels the pain occasionally in her groin and this is normal also. There are no symptoms or signs of cauda equine syndrome. As she had not taken any analgesia, she is advised to take some painkillers and call back if the pain does not settle. Four hours later she collapses and dies in casualty. Post mortem reveals a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Discussion

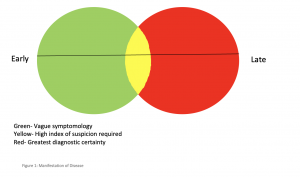

These cases aim to demonstrate the well-known ambiguity of disease presentation. However, the cases differ in the time scale between what may be considered the start of the presentation and its final manifestation in a clinically recognizable form. Figure 1 aims to demonstrate this.

Whether one is able to make a successful diagnosis depends upon where along the continuum, expressed above in the figure as the timeline running through the diagram, the patient presents. In the green area symptoms are likely to be vague and examination and investigations may not yield meaningful results. In the red area the diagnosis may be obvious with the patient presenting with “textbook” signs and symptoms and investigations pointing to a high probability of disease.

Casualty physicians operate mainly in the red area with patients presenting late in the illness with classical symptoms. As general practitioners we are often operating in the green zone, an area of vague symptomology and sometimes aimless groping in the dark. Hence the importance of safety netting and constant review of patients in whom the symptoms fail to resolve or progress further.

Worryingly though for GPs case 3 demonstrates that the best of safety netting may not sometimes be adequate; a serious, life threatening condition masquerading as something benign, only for it to show its devastating effects in a matter of hours.

The casualty physician who saw the same patient, whilst her presentation was in the red zone, may well have pondered on how the GP who saw her few hours earlier managed to miss the diagnosis. It seems that this patient missed the yellow zone of figure 1, or was unfortunately not attended to as she passed through it.

Cases 1 and 2 seem to have a definitive phase through this transformative form of the presentation when the illness briefly seems to mimic something clinically recognizable. A high index of suspicion is required at this stage to help make the diagnosis. It would be easy to miss this phase in patients who visit their doctor often when it is all too easy to put down their symptoms to psychosomatic causes.

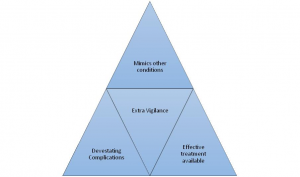

All of the above cases mimicked other conditions (fibromyalgia, chest infection, musculoskeletal back pain), can have devastating complications (joint deformity and death) and at least in cases 1 and 2 have effective treatments. If the discerning doctor is not on the lookout, the disease may well progress from yellow to red (or beyond!) at which point unnecessary distress may result to the patient.

In summary, it is useful to consider the disease as a separate entity in the consultation process and be wary that it may take many forms before it lifts its veil to fully reveal itself. Whereas illness is often present, disease may lurk in and out of the GP consultation like a stealthy thief only to be caught by the most attentive of detectives.

* Case details and patient demographics have been changed.

Featured image by Crawford Jolly on Unsplash