The waiting time to receive a dementia diagnosis in the NHS is increasing: the 2021 National Audit of Dementia found that the average waiting time from referral to diagnosis increased from 13 weeks in 2019 to 17.7 weeks in 2021.1 Currently, blood test results and a brief cognitive assessment (such as MMSE, MOCA or GPCOG) are required to refer a patient with memory or cognition concerns from primary care to a specialist memory clinic. While these blood tests largely exclude non-dementia causes of cognitive impairment, they do not offer any specific prognostic value for particular dementia diagnoses. Accordingly, a proportion of memory clinic referrals are ultimately found to be false-positives, which contribute to the substantial and growing referral waiting time.

Accordingly, a proportion of memory clinic referrals are ultimately found to be false-positives, which contribute to the substantial and growing referral waiting time.

Until recently, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) plasma biomarkers have been mostly studied in patients from specialised memory clinics.2,3,4 This raises the question of whether the promising results from memory clinic populations can be generalised and directly translated to primary care cohorts, in which the population of older patients with cognitive symptoms is much more heterogeneous and includes various pathologies and multi-comorbidities such as hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and kidney and cardiovascular diseases. It has been suggested that testing for particular AD plasma biomarkers in primary care in patients with suspected mild cognitive impairment (based on a brief cognitive assessment) could meaningfully improve the efficiency of memory clinic referrals – and therefore reduce the waiting time – by reducing the rates of false-positive referrals.5,6 To test this hypothesis, a large prospective primary care-based study of 1007 participants without dementia aged 79–94 years in the longitudinal population-based German Study on Ageing, Cognition and Dementia in Primary Care Patients was carried out.7 The study measured the plasma levels of the AD biomarkers Aβ40, Aβ42, P-tau181, NfL, and GFAP. It sought to determine the association between AD plasma biomarker levels and cognitive decline and disease progression, and the capacity of these biomarkers to improve the prediction of future clinically-diagnosed AD.

The study found that the AD plasma biomarkers are associated with an increased risk of progressing to clinically-diagnosed AD during 8 years of follow-up in individuals without dementia aged 79–94 years in a heterogenous primary care population. It also found that plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and GFAP level, together with MMSE score, improved the diagnosis precision of future clinically-diagnosed AD in participants with a lower MMSE score (≤27). Finally, in a subset of patients with a matched sample after 8 years of follow-up, all plasma biomarkers showed time-dependent changes that could be considered when assessing the risk of progressing to clinically-diagnosed AD.

A notable drawback of the study’s findings is the lower sensitivity – meaning a substantial rate of false-negatives – which could lead to delays in care or misdiagnosis.

The findings suggests that the use of AD plasma biomarkers in primary care could reduce the rate of false-positive referrals to memory clinics (confirmatory testing in those clinics would still be required) and, therefore, reduce the waiting times for these services. They also imply that evaluating the dynamic changes of these biomarkers, rather than depending on a single measurement at a specific time, might offer greater utility for following-up patients and evaluating prognosis in the preclinical stage of AD. Perhaps most importantly, since AD begins 20 or more years before symptoms arise,7 and treating it at an early stage is likely to result in more clinically meaningful effects,8,9,10 the use of AD plasma biomarkers in primary care could improve patient outcomes. A notable drawback of the study’s findings is the lower sensitivity – meaning a substantial rate of false-negatives – which could lead to delays in care or misdiagnosis.

Putting aside the questions of who will do this additional work, at what point in the GP’s already over-filled day will this work take place, and where the money to enable it will come from, there appears to be a potential role for AD plasma biomarkers in primary care to improve the efficiency of memory clinic referrals, reduce waiting times in these services, and improve patient outcomes.

References

- O Corrado, R Essel, C Fitch-Bunce, et al. National Audit of Dementia: Memory Assessment Services Spotlight Audit 2021. August 2022. https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ref-317-NAD-Memory-Assessment-Services-Spotlight-Audit-2021_FINAL.pdf [accessed 21 September 2024]

- IMW Verberk, MB Laarhuis, KA van den Bosch. Serum markers glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light for prognosis and monitoring in cognitively normal older people: a prospective memory clinic-based cohort study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity Feb 2021; 2(2): e87-e95. DOI: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30061-1

- N Mattsson-Carlgren, G Salvadó, NJ Ashton, et al. Prediction of Longitudinal Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease Using Plasma Biomarkers. JAMA Neurology 2023; 80(4): 360–369. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.5272

- J Simrén, A Leuzy, TK Karikari, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia July 2021; 17(7): 1145-1156. DOI: 10.1002/alz.12283.

- S Mattke, SK Cho, T Bittner, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s pathology and the diagnostic process for a disease-modifying treatment: Projecting the impact on the cost and wait times. Alzheimer’s & Dementia August 2020; 12(1): e12081. DOI: 10.1002/dad2.12081.

- D Angioni, J Delrieu, O Hansson, O. et al. Blood Biomarkers from Research Use to Clinical Practice: What Must Be Done? A Report from the EU/US CTAD Task Force. Journal of the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022; 9: 569-579. DOI: 10.14283/jpad.2022.85

- PV Martino-Adami, M Chatterjee, L Kleineidam, et al. Prognostic value of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers in the oldest-old: a prospective primary care-based study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe August 2024; 45: 101030. DOI: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101030

- JR Sims, JA Zimmer, CD Evans, et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023; 330(6): 512-527. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- H Hampel, R Au, S Mattke, et al. Designing the next-generation clinical care pathway for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Aging 2022; 2: 692–703. DOI: 10.1038/s43587-022-00269-x

- PS Aisen, GA Jimenez-Maggiora, MS Rafii, et al. Early-stage Alzheimer disease: getting trial-ready. Nature Reviews Neurology 2022; 18: 389-399. DOI: 10.1038/s41582-022-00645-6

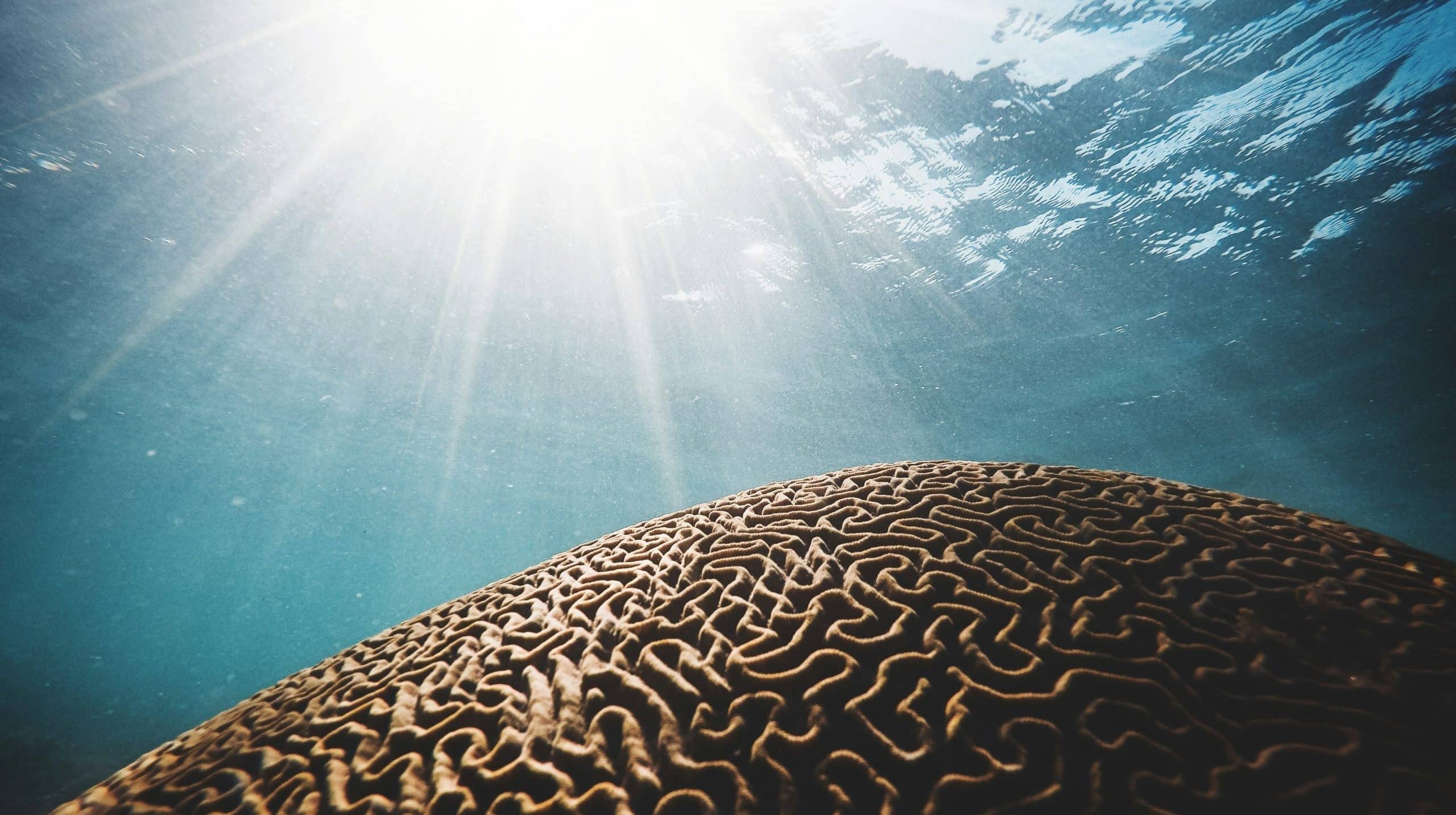

Featured Photo by Daniel Öberg on Unsplash