Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Any consultation can in theory involve just two participants, although in practice a third is almost always present, whether in the room or behind the scenes, contributing their own distinct views and expectations to the medical encounter. This shadowy figure might be a patient’s family member, friend, or other informal health advisor, whose opinion carries a certain weight, either because it is well-informed or, more often, simply because it is trusted. We do not occupy the doctor’s seat in splendid isolation either, but in the invisible company of a career’s worth of teachers, colleagues, and former patients, ghosts preserved within the professional machine; some days the room can feel pretty crowded.

…we are in constant motion too, doing our best to keep up with a set of relationships less like a triangle and more like an interpersonal three-body problem.

When desktop computers came into widespread use in general practice in the early 1990s, they were initially seen as a third person in the room too, representing the official record of the patient’s life as seen through the medical lens.1,2 The subsequent arrival of the World Wide Web made the computer not just a biographical repository for the doctor’s use, but a portal through which patients could access information about their symptoms or diagnosis, even if they didn’t always know what to make of it. Widely available Generative Artificial Intelligence applications now look set to bridge this interpretive gap between an individual and the store of medical knowledge available to them online. AI as a third party in the consultation may therefore be a new phenomenon, even though “triadic care” in general is not.3

In the context of a relationship between two people, a third party can function in a number of ways, adding their weight to one side’s point of view, buffering tension between the two, or forming a competing relationship with one or the other. In the classical drama triangle involving a Victim, a Persecutor, and a Rescuer, the doctor might try to rescue a patient from their symptoms, for example, while at the same time the patient looks to an AI to help them overcome the doctor’s perceived resistance to their own preferred course of action.4 There is certainly a growing sense of push-back against what is seen as professional privilege in the consultation, and we cannot take it for granted that our own role is either the same as it was yesterday, or even what we think it is today.5 A triangle is flat and static, while the relationships it represents are often more fluid and ambiguous.

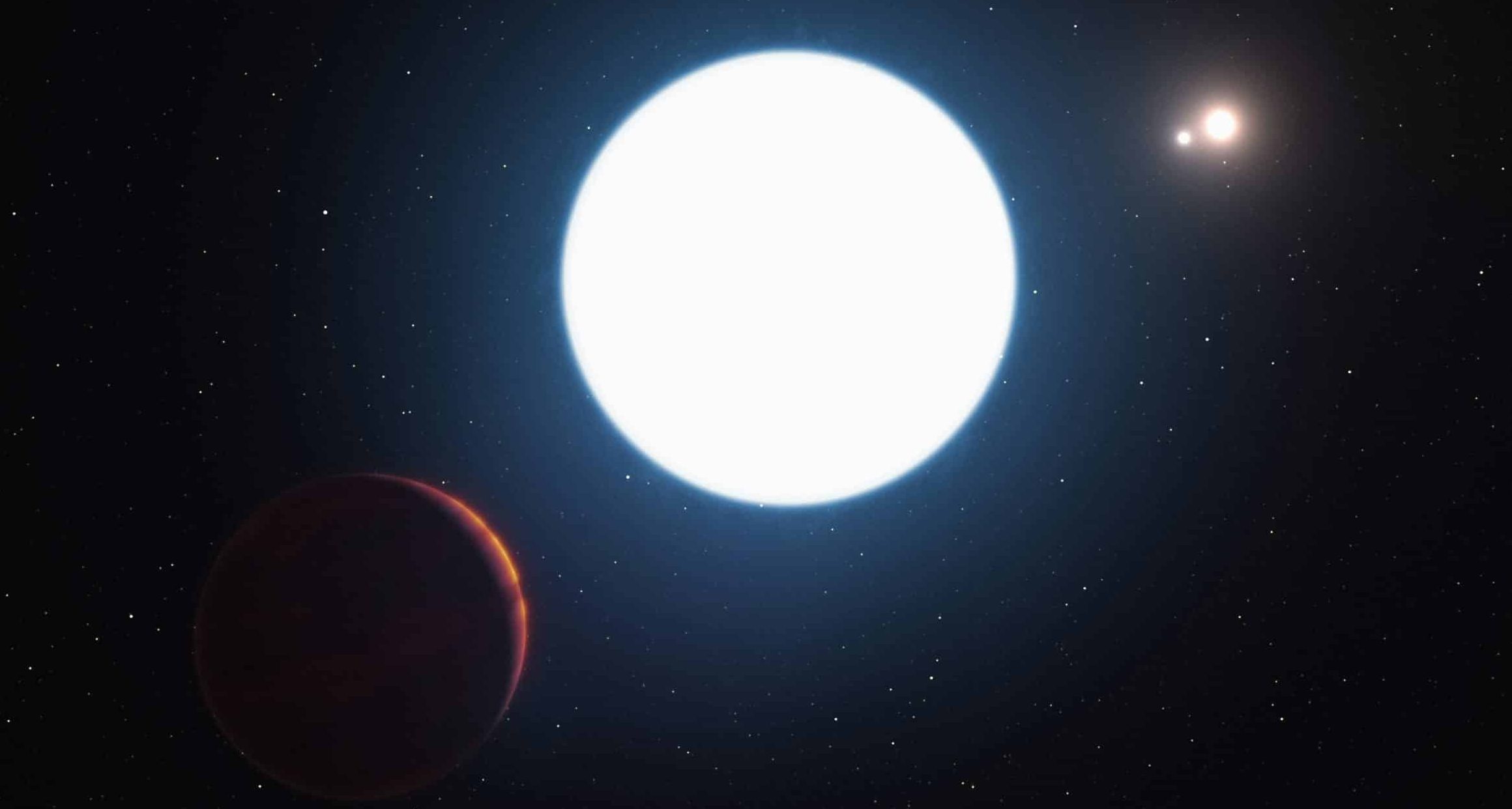

Most of us probably accept the idea that the Moon moves predictably around the Earth, just as the Earth does around the Sun, and it is easy to assume that this sets the tone for most of what happens elsewhere in the cosmos. Cixin Liu’s novel The Three Body Problem describes a civilisation on a planet orbiting not one sun, but three, which also orbit each other. Although the story is fictional, triple star systems are not uncommon, and we can in theory apply Newton’s laws to them in the same way that we do to our own. While it is straightforward to model the orbit of a smaller body around a larger one, however, it is far harder in practice to predict how three of similar size will interact in three-dimensional space, as each is pulled in different and constantly changing directions by the gravitational attraction of the others: this is the three-body problem.6

If GPs seem at times to practise idiosyncratically or inconsistently, this is hardly surprising: we are in constant motion too, doing our best to keep up with a set of relationships less like a triangle and more like an interpersonal three-body problem. The physics of Cixin Liu’s alien world make it a hazardous place to live, and the consultation can sometimes also feel like a minefield of hidden agendas, competing interests, and impossible choices. A triple star system seen from a distance may look like a single sun, just as a consultation in general practice may appear straightforward to the casual observer, and yet the appearance of both is deceptive. When we consider the emerging role of AI in healthcare, it is therefore not the case that something simple has suddenly become complex, but rather that our place within the existing complexity is changing.

This has always been the strength of general practice: not necessarily to make perfect sense of things, and certainly not to know everything, but to be there for someone when they need us.

The current drive towards larger practices, greater organisational efficiency, and the taskification of patient care all represent a consistent direction of travel from a personal to an industrial model of healthcare.7 There may always have been a third seat in the room with us, but it is now occupied less often by a person than by something else which exerts a much stronger gravitational force: a care pathway, arrowed and unambiguous; a policy to which our diversity must conform; or – how could it be otherwise? – an AI, attempting to make sense of a world for others that it can never experience itself. It is tempting to try to bypass this, to shrink the format of our interactions with patients in pursuit of more dyadic care, and yet it is a temptation we should resist. GPs have a weaker pull in this star system now; the only way we can simplify our three-body problem is to remove ourselves from it.

Before we become too glum, however, it is worth reflecting that complexity is an essential feature of the universe in which we live, and one to whose management GPs are well-suited.8 If the three-body problem stands for a system that is complex and unpredictable, it also represents the potential for small masses at close quarters to have a greater impact than much larger ones at a distance. This has always been the strength of general practice: not necessarily to make perfect sense of things, and certainly not to know everything, but to be there for someone when they need us. Doctors no longer have the professional authority or autonomy that we once did, and that may be no bad thing, but in a healthcare system which often feels distant, chaotic, or even hostile, we can still aim to be a trusted third person in the room.

References

1. Chris Watkins, Ian Harvey, Carole Langley, Alex Faulkner, Selena Gray, General practitioners’ use of computers during the consultation, British Journal of General Practice, 1999, 49, 381-383

2. Rouf E, Whittle J, Lu N, Schwartz MD. Computers in the exam room: differences in physician-patient interaction may be due to physician experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):43-8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0112-9. PMID: 17351838; PMCID: PMC1824776.

3. David Fraile Navaro, Marcus Lewis, Charlotte Blease, Rupal Shah, Sara Riggare, Sylvie Delacroix, Richard Lehman, Generative AI and the changing dynamics of clinical consultations, BMJ 2025; 391: e085325 doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2025-085325

4. Karpman S, Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 7 (26), 39-43, 1968

5. Abigail McNiven, Amy Dobson, Katie Read, Sharon Dixon, ‘My patients are “gunning for a fight” that I don’t want’: reflecting on feeling dismissed and conflict- expectant consultations, British Journal of General Practice 2025; 75 (754): 234-236. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp25X741561

6. Wikipedia contributors, “Three-body problem,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Three-body_problem&oldid=1324538302 (accessed December 3, 2025)

7. Rasmussen AN, Mcdermott I, Spooner S. Taskification in general practice: A solution to, or an aggravator of, the workforce crisis? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2025 Nov 19:13558196251400266. doi: 10.1177/13558196251400266

8. Kieran Sweeney, Complexity in Primary Care: Understanding its Value, Radcliffe, 2006

Featured Photo by NASA Hubble Space Telescope on Unsplash