In the interests of healthcare economy and its professionals’ delivery agility many – politicians, planners and now younger doctors – are vaunting the merits of more remote and procedurally algorithmic practice. These both assume and predicate the irrelevance of personal continuity of care. Yet much gets lost. What? Three authentic tales from a single practice illustrate.

- March 1999. Shoots

The neat and rounded handwriting on the envelope is unfamiliar to me. It is topped in emphatic capitals PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL, so the receptionists have left it for me to open.

The letter has clearly been written thoughtfully and slowly. I quickly look to the bottom of the second page where, at the letter’s end, I find the writer’s very readable name: Tracey*. Memories flood back in fragments – her face, her voice and a collage of snapshots from her teenage years’ many consultations with me. I read her letter slowly – much as, I imagine, she had written it:

“Dear Doctor

I hope you remember me because it must be at least five years since I last saw you – it was just after I’d left Art School. I just wanted to say a big ‘thank you’ for all you did and how my life is now, so I’m certainly not going to forget you!… “

She specifies this: the reciprocal warmth and love she finds with Rob; the haven-home and joyous infant they have created; their sibling-like careers as art practitioners and teachers. All of this warms me, but it is the last paragraph that affects me most:

“Anyway, what I want to say is, if I hadn’t sat in your surgery all those years having those conversations, none of this would have happened! I would never have found what I wanted or had the confidence to have it. Sometimes we need to feed off other people’s faith and experience, don’t you think?”

My memory reels back, to ‘those conversations’.

1a. 1984-1994. Tracey was age ten when I first saw her: she was brought by her foster mother, for Social Services’ regulated health-checks. I had already gleaned much that was grim and would remain diplomatically unmentioned for many years: the decisive court-actioned separation from her parents when she was five due to their drug-fuelled, hazardous parental incompetence and tempestuous mal-union. Her subsequent official placements were deemed ‘unsatisfactory’ to help her heal, let alone grow well. The foster mother – a dutiful, earnest, woodenly diligent woman, I thought – remained Tracey’s last and more secure, if rather joyless, base for several years.

“Sometimes we need to feed off other people’s faith and experience.”

Tracey had always, yet increasingly, showed pleasured interest in the ambience of my room: its gallery of colourful expressionist and impressionist prints, its scattering of wooden carved animals and birds. Such engaged spirit encouraged me, but much of what she told me about her life did not: she was now truanting from school, dope-smoking with other truanters and was heading for a no-qualifications-no-plan-no-job drift.

One summer’s afternoon in 1989 my surgery’s wall’s colourful prints glow in the streaming sunlight. As Tracey enters the room she rotates her gaze slowly to savour the artworks; I think she wants me to notice her deliberation. She sits down with a kind of meditative grace.

I look toward her, beckoning her first words.

‘I love this room, doctor…’

‘What about it?…’

‘Oh, I suppose all your pictures, especially … the colours … all the ways they make me feel.’

‘Is there one in particular? A favourite, maybe?’

Tracey points to a Matisse. I ask her to share what she finds ‘out there’, in the picture. I then venture, ‘Tracey, all that you find in the painting is also in you. That’s why you feel like you do…’.

She seems intrigued by this, hungry for more. I ask if she has ever looked at art anywhere else. She has not. She is not even aware of London’s free art galleries and museums: Her foster mother’s stalwart responsibility occupies a very different territory.

I suggest she visits Tate Britain. ‘If you want to, you can tell me what you find’, I conclude.

Tracey returns three weeks later and describes what I know I remotely hoped for, yet could never prescribe: she had discovered not just many more pictures, but a much larger part of herself.

This fresh path widens, then lengthens, as she comes every few weeks to talk and to take in some of my encouragement and suggestions. She finds an Art Foundation course at an FE college: ‘I love it! I know what I want to do!’, she says while unrolling one of her rawly gifted creations to show me.

I had become long-term in loco parentis. If not me, who?

Four years later she is coming to say goodbye. She has graduated ‘with Distinction!’ she tells me with a pride that is joyfully shared but not self-preening. Behind her is standing a warmly-gazed, gently mannered young man who has said nothing but seems intimately attuned to her. She introduces us: ‘This is Rob. We were students together and now we’re a couple … We’re moving out of London, to see what kind of life we can make together. Before we go I wanted you to meet Rob and to say goodbye…’

I shake Rob’s hand and then Tracey embraces me: we are both discretely, restrainedly, tearful.

- 1990-2010. Roots

Violet was little known to me; she seemed happily and actively independent and came only for her well-controlled hypertension and mild degenerative musculoskeletal complaints. She told me that she lived alone; her husband had died many years ago and they had no children. She had worked in the Civil Service for forty years: her proud and disciplined abilities had promoted her to Senior Clerical Office by the time of her retirement.

2a. 2011-2015. The pattern of this lifelong, apparently cheerful, alacrity begins to crumble alongside the skeletal structures of her lumber spine. Within months her life is unprecedently riven with bone-on-bone and nerve-entrapment pains. X-rays validate the diagnostic hypothesis: thinning, grossly arthritic vertebrae, some collapsed; drastically collapsed cartilaginous discs.

Serial X-rays and sophisticated scans chart an inexorable progression of these. She is receiving much specialist care: metabolic bone physicians, neurosurgeons and pain clinics all administer their remedies – bone-protection drugs, nerve blocks, spinal injections and surgery, TENS machines and various ‘advanced’, often combined, opiates and analgesics … All are tried, and all fail.

Violet now seeks me out, she finds my familiarity comforting and reassuring. She has become largely confined to her flat and cannot come to see me, so she is tenacious in her phone calls. She describes the excruciations, the locations, the patterns of her pains. No, she does not want me to arrange a Home Help; her ‘trusty neighbours’ do her shopping and ‘it’s important I do what I can, doctor, I still do my own housework, you know. I won’t give up!’.

I, and my colleagueial brethren, have run out of options. ‘But isn’t there something else you can do?’ asks her plaintive telephoned voice. I feel helpless.

I decide I can, at least, visit her.

She comes to the door, faltering slowly with pain yet determination and steadied with a stick. Her eyes are bright with friendly gratitude and she turns to lead me into her living room, a meticulously clean and orderly space still centred around its high quality 1950s furniture: something stopped here, I think.

…her living room, a meticulously clean and orderly space still centred around its high quality 1950s furniture: something stopped here, I think.

Violet watches me gazing at these two men from so long ago yet still so much alive for her. She seems to want me to look.

‘Who are they?’, I ask with a soft reverence.

She limps across to point at each. ‘That’s Jack, my only and lovely brother … and that’s Bert, my darling and certainly only husband … they really loved one another, too, doctor…’

‘Both gone?’ I venture, to confirm.

‘Oh yes, long ago.’ She sinks into a chair and beckons me to sit opposite, to talk.

‘Jack died in Burma, in the War. Bert survived the War but died of a burst stomach ulcer in 1953; that was just six months after our only child was stillborn … Bert was an only child, too…’

‘So now, after such pain and losses, and all your courage, you have no family…’ I could say more, but do not.

She cries softly as she tells me of the eternal embers of grief, the price of courage, and the undertow of loneliness.

‘I’m sorry I can’t do more for your pain, at least’, I say.

‘Oh no, doctor. Your knowing and understanding this helps me bear it all, you see.’

And so it was.

“Your knowing and understanding this helps me bear it all.”

She died, apparently asleep, age 93, found by her ‘trusty neighbours’.

She had managed to do her housework the day before.

- 2003. Rootless

I am lagging behind the herd: surrounding practices are becoming rapidly computerised – some with exploratory zeal, others with grudging and anxious scepticism.

Dr C is one of the former, despite his similar age to mine. He is sent by the authorities to encourage and persuade me to quicken my pace in joining the mass migration to digitalisation. I find Dr C courteous, kindly and patiently intelligent – a fine patrician-physician, I think.

‘You really shouldn’t worry; it’s surprisingly easy. Sit in on one of my surgeries and I can show you – my computer even responds to my voice!’ he says with boyish pride.

A week later Dr C shows me around his very modern and very large purpose-built polyclinic. I quickly notice that the patients are (mostly) trained to electronically register their arrival and are, therefore, rarely received by the receptionists, who are occupied with other electronic tasks. I also notice that Dr C does not seem to know his receptionists.

An hour later I am sat behind him and slightly in front of the attending patients, and to their left side. Patients have been informed, and given the choice about me – ‘a colleague of Dr C’ – quietly witnessing his consultations.

He introduces Molly to me and explains, with gentle sympathy, she has been having dizzy spells. Molly nods with trust and deference. She is in her early forties, demure-smart, carefully coiffed and discretely made-up.

‘How are you, Molly?’, he asks kindly.

‘Oh, OK I think … just the same, really…’.

‘Good. Nothing new then … Well, let’s see’, he turns to the screen and scrolls down, summarising for us both, ‘my general, neuro, cardiovascular examinations all entirely normal. Chest X-ray, ECG, and full blood-screens all reassuringly OK … So … we can pretty sure there’s nothing serious here…’ As he is scrolling up again to be sure, I think, he glances at her briefly before asking: ‘Everything alright otherwise, Molly … at home, for instance … anything else?’.

Dr C is gazing at the screen when she answers. Molly inspires deeply to hold her breath for a few seconds before exhaling. She looks up into the right-hand corner of the room with incipiently tearful eyes as, shifting sharply in her seat, she decisively folds her arms in front of her and simultaneously crosses her right thigh over her left while tucking the foot tightly behind the other calf.

Dr C is gazing at the screen when she answers.

She immures herself; no-one must know! I am thinking.

Dr C wraps up the consultation: ‘So, Molly, it’s nothing to worry about – just common dizzy spells. You can continue taking those steadying tablets and come and see me again when you want.’

After Molly closed the door behind her he turns to me; he seems pleased.

‘Well, what do you think?’ His question seems open in heart and mind.

I describe what I saw – the few seconds of Molly’s involuntary body-behaviour – and what I thought it meant … all while he was screen-gazing.

‘Oh,’ he says, his voice failing, ‘that’s disconcerting…’

I describe what I saw – the few seconds of Molly’s involuntary body-behaviour … all while he was screen-gazing.

‘Well, I think I would have noticed all that a few years ago, before I became computerised.’ He then cheers himself: ‘But this is a new era now … maybe those things don’t really matter so much … it’s the physical diagnosis and intervention that count.’

I disagreed. Over mid-morning coffee we argued – with reassuring courtesy and amiable respect – about the nature and future of general practice.

- 2021. Retrospect

Nearly twenty years later I can see that Dr C’s predictions and expedience are clearly on the right side of history: mine were not.

And yet, with age, as my practitioner-self recedes and my patient-self looms, I know what kind of doctors I want for myself.

* All patient names and details have been changed.

David Zigmond © 2021

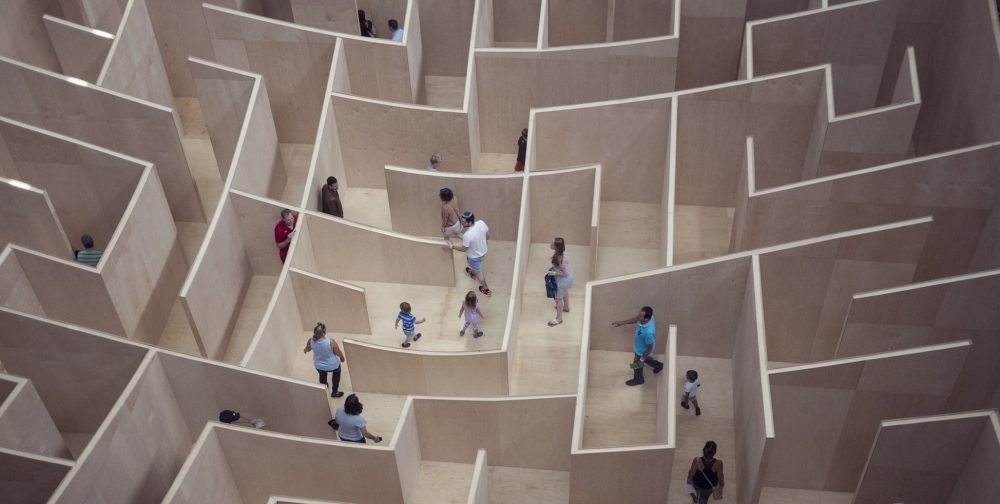

Featured photo by Susan Q Yin on Unsplash