Andrew Papanikitas is deputy editor of the BJGP, and a GP in Oxford. He is on Twitter: @gentlemedic

Andrew Papanikitas is deputy editor of the BJGP, and a GP in Oxford. He is on Twitter: @gentlemedic

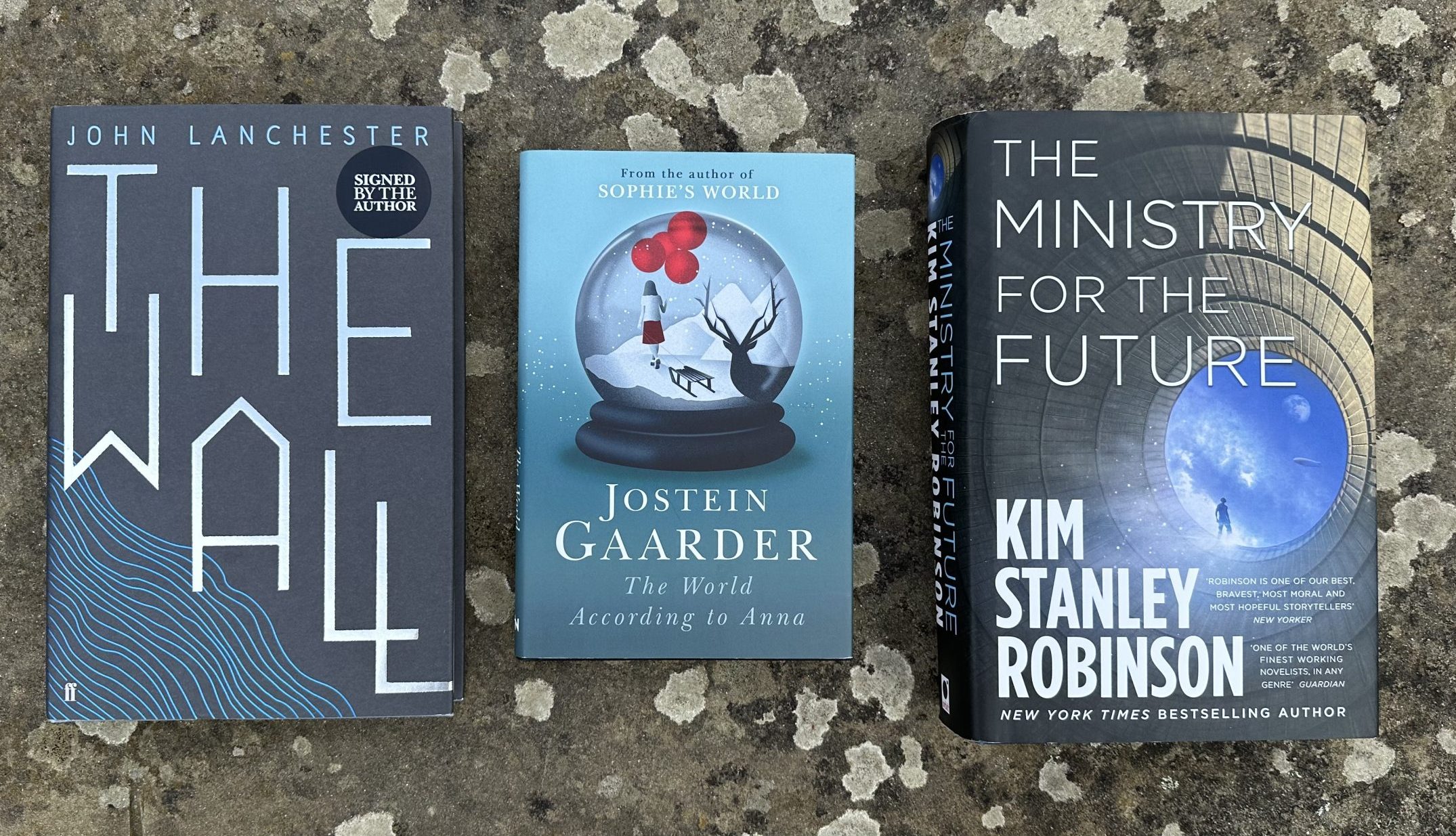

In the summer before COVID-19, I read three works of fiction (one after another) that changed my perspective on the world and our place in it. Each has a very different mood, and perhaps I am glad I read them in the order that I read them: The Wall (John Lanchester), The World according to Anna (Jostein Gaarder), and The Ministry for Future (Kim Stanley Robinson).

The international upheaval and mass migration have led to a one-party state erecting a wall around mainland Britain.

The Wall is a grim near-future British dystopia. The sea levels have risen and become more hostile to marine life. The international upheaval and mass migration have led to a one-party state erecting a wall around mainland Britain. Everyone has to do national service on the wall to keep foreigners out. Failure results in exile. People still have biscuits and smartphones, but there are no beaches. I read Lanchester’s novel in two sittings, with Donald Trump’s hateful rhetoric about building a wall echoing in recent news. The novel channels the mood of a variety of British fictional dystopias, and whilst I can’t infer any influences, it made me think of Orwell’s 1984 and of The Guardians by John Christopher. The plot draws you in with a first person perspective, you see, hear and feel the experiences of a new conscript on the wall. You feel his anger at the generation who broke the world, his anger at his own parents. The threats that he encounters in the narrative are plausible, for him they no longer existential. This is an England that is hostile to outsiders at the point of a a machine-gun. ‘Stop the boats’ has become the way of life, there are smartphone games for the masses and (air) travel abroad is only available to the elite. The emotions that the narrative excited in me were anger and fear. It made me want to learn more, to see what might be done. The Wall was long-listed for the Booker Prize, and perhaps one day it will be an A-level or University literature text. I read it with future generations looking over my shoulder.

I find it amazing that reading this book was the first time that the term ‘intergenerational justice’ became meaningful for me.

The world according to Anna is typical Jostein Gaarder in that a cultural or philosophical phenomenon is encountered by a child in a transformative experience for the reader. A teenage girl experiences climate change, mass migration and animal species extinction in her own time and in the future as she dreams herself to have become a grandmother. I find it amazing that reading this book was the first time that the term ‘intergenerational justice’ became meaningful for me. This is in a may ways a young adult book. It is tinged with sadness as climate change erodes the beauty of winter and the nordic traditions that come with it in the present. We see a parallel sadness among the climate refugees, for them their traditions have barely survived the obliteration of their homes by desert. It is philosophical, political and teaches through its protagonists’ discussion and questions. Threaded though the story is Anna’s concern for the extinction of animal species, and her plan to bring this into public consciousness. Anna and her youth movement co-exist as a literary mirror image of Greta Thunberg and the ‘School-strike for climate’. This is a hopeful book. I wonder if the feeling it left me with was a mixture of nostalgic grief and new hope. It was a good antidote to The Wall, and triggered a foray in to Gaarder’s other books.

A ministry lobbies governments and national banks from Switzerland, climate terrorists kidnap billionaires and shoot down planes, a community take a deal to abandon their town to rewinding…

The final novel I would like to mention here is The Ministry for the Future. Don’t be put off by the tome-like page count, it is a page-turner. Kim Stanley Robinson is best known for the ‘Mars’ series of novels about the human colonisation and terraforming of the red planet. The story begins with a catastrophic heatwave experienced as a human tragedy leading to a United Nations response, the titular ‘Ministry for the future.’ The book is a collection of threaded narratives about climate change and everything it might take to reverse it. A ministry lobbies governments and national banks from Switzerland, climate terrorists kidnap billionaires and shoot down planes, a community take a deal to abandon their town to rewinding, scientists attempt to re-ice the poles and a burnt out humanitarian worker embarks on his own tragic quest to avenge the world. Interleaved between chapters are a series of poetic riddles guest-starring the phenomena that have resulted in our current predicament. Sometimes the threads cross. The hopefulness lies in the possibilities. The world in this book do not follow one strategy to fix the problem, they pursue all of them in a a typically human united and divided, altruistic and self interested way. The conclusion of this story is a world we would wish for. The first chapter left me anxious, but this gradually transformed into an urgent need to see what would happen and how we would be saved. I wanted to learn more, about economics, about climate change and its antidotes and to foster this awareness in others.

I imagine that these three stories will not suit everyone. I imagine that for some (hopefully very few) these will be different examples of art with no message applicable to our times. For me they sparked new-awareness and new interests, and the hope that if we work together (even in our own ways) we can save life on Earth.

Featured Books

John Lanchester, The Wall, Faber & Faber, ISBN: 9780571298730, PB, £9.99

Jostein Gaarder, The World According to Anna, Orion Books, ISBN: 9780297609735, HB, £12.99

Kim Stanley Robinson, The Ministry for the Future, Orbit Books, ISBN: 9780356508832, HB, £20