Graham Easton is a GP and Honorary Professor of Clinical Communication Skills at Queen Mary University of London. He is particularly interested in the power of stories in medicine and medical education.

Graham Easton is a GP and Honorary Professor of Clinical Communication Skills at Queen Mary University of London. He is particularly interested in the power of stories in medicine and medical education.

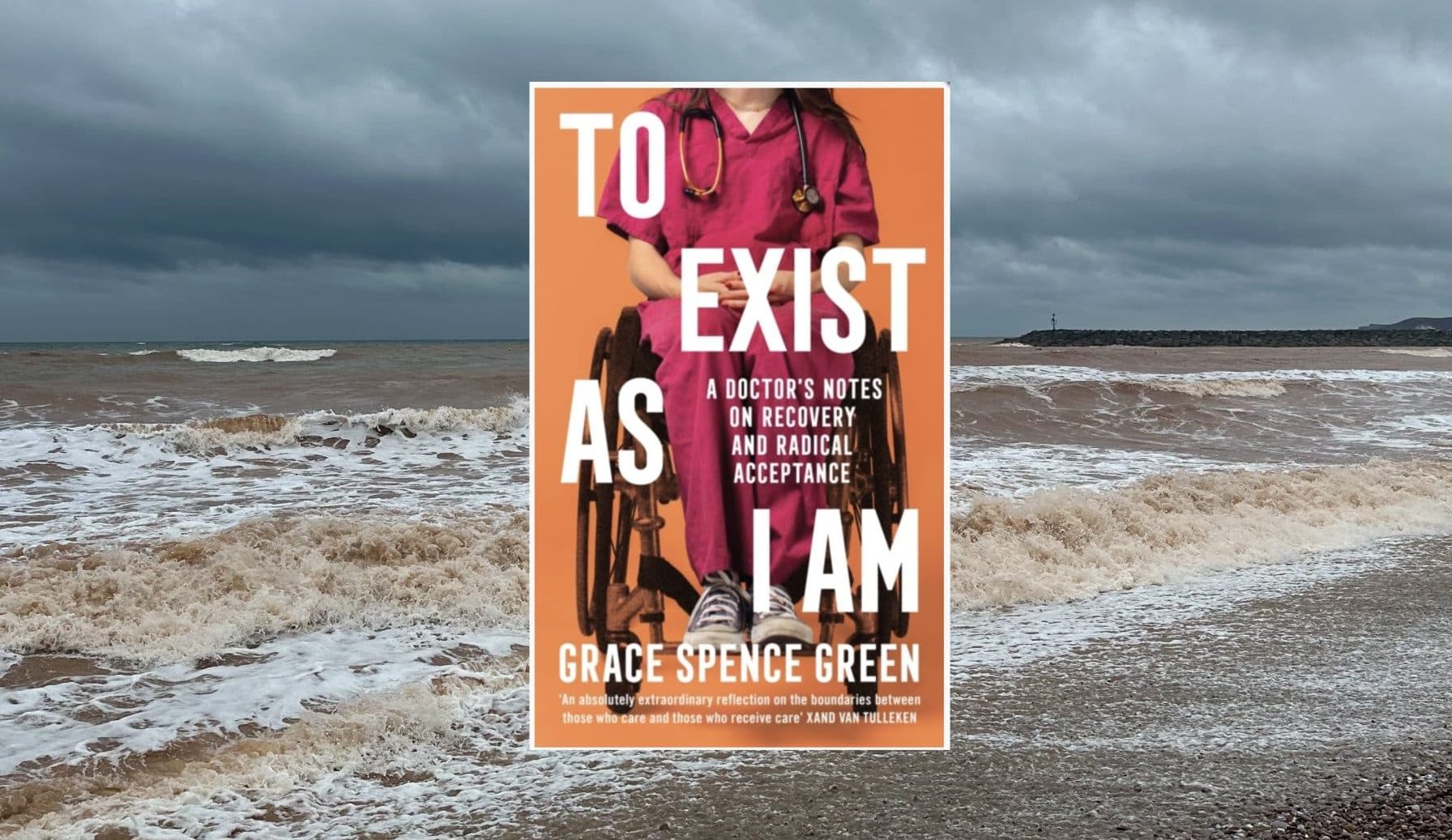

In 2018, aged twenty-two and a fourth-year medical student, Grace Spence Green’s spine was broken by a man who fell on her when he jumped from the third floor of a shopping centre. To Exist As I Am chronicles Grace’s journey from medical student to spinal injury patient, and then to qualified doctor, wheelchair-user, and disability activist. She doesn’t pull any punches; her story is honest, intimate, sometimes funny, and frequently furious. It’s a rare insight into what it means to be a patient, and a doctor, and the fragile thread that links the two. She has made me think about these things in new ways.

What really hit me was her crushing critique of the corrosive stories we tell about illness, disability and healing, and the unarguable (but so often sidelined) power of empathy and kindness in healthcare. And even after 30 years as a GP, I picked up plenty of new do’s and don’ts about what to say and how to be with patients – particularly people with disabilities. I know people often say this in book reviews – but I really do think this should be required reading for medical students and healthcare professionals.

…even after 30 years as a GP, I picked up plenty of new do’s and don’ts about what to say and how to be with patients – particularly people with disabilities.

For a long time, Grace felt defined by the sensational headlines written about her, as if she was an anecdote for strangers to tell others (and, by the way, she holds no grudge against the man who fell on her). But she’s had enough of being boiled down to a story that someone else tells about her. She says that her experience as an inpatient (at The Royal London Hospital and then at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital at Stanmore) and as a visibly disabled person has radicalised her. She now sees how she and other disabled people are systematically excluded; not just from specific spaces (there are many upsetting stories about ramps, pubs, toilets, medical school teaching sessions and hospital canteens), but also from “specific narratives [she] is allowed to follow – tropes to fall in with”.

The dominant narrative she butts up against, time and again, is the one that goes: “There is something wrong with you – how can it/you be fixed?” It maps closely onto what illness narratives guru Arthur Frank would call a “Restitution narrative” (I was ill, I suffered, I was treated and I was restored to full health) – the preferred narrative of modern Western medicine.1 It was, for a while, the heroic story she told herself; triumphantly striding out of hospital, miraculously healed. But this sort of narrative risks seeing long-term illness or disability as somehow shameful or wrong, an embarrassing let-down. Grace writes that people often ask intrusive questions about what happened to her, and “Is there anything that can be done?” or “It’s not permanent I hope?”. This makes her feel as though her current existence is not enough for people. It reminded me of the dangerous urge people have, when someone has fainted on the tube, to yank them back to their feet or prop them up against the seats. They desperately want to restore their image of normality – even though it risks brain damage. Disability, she reminds us, is a valid way of existing. It’s not a perpetual state of sickness or defectiveness that needs fixing.

This restitution narrative often makes people pity her. She’s revealing about this – particularly how they focus on her wheelchair, often seen as a sign of weakness and failure. Strangers in the supermarket, or even at work, come up to her and tell her how bad they feel for her. “Oh isn’t it awful being in a wheelchair?” they say, projecting their version of visible disability onto her, even though she now sees it as a valued tool for mobility and independence. She made me smile (uncomfortably) with: “As if you’d ever go up to an elderly person in public and say, ‘isn’t it awful being old? I knew someone who was old once, and God it just looks dreadful!’”. She describes how the term “Wheelchair-bound” makes her grind her teeth, and the damaging subtext of hopelessness she hears when doctors say someone is “confined to a wheelchair”.

Grace acknowledges that for twenty-two years, she was also a member of the restitution narrative club; after all, that’s the story society and medical training rams down our throats. So she doesn’t blame us exactly, but she is angry about it and thinks we could all do better. For example, how we teach about disability at medical school. When she returned to King’s College to finish her studies, she noticed how her condition – and many others – were so often framed as catastrophes, disasters to be avoided at all costs. The negativity felt so stark, now they could be talking about her. Yes of course, she says, doctors need to be taught these things and understand their gravity. But she wonders, could the way we choose to frame these conditions as worst-case scenarios and catastrophes be influencing how the people living with them are treated?

She jokes that her time as a spinal injury patient taught her more about being a doctor than any medical placement. But it’s not a joke.

She jokes that her time as a spinal injury patient taught her more about being a doctor than any medical placement. But it’s not a joke. Her empathy for patients is now rooted in raw experience. She speaks of the fear and disorientation of losing control of your body, and of having your story flattened into numbers and rating scales. A porter once called her “a chair.” A colleague grabbed her wheelchair and pushed her somewhere she didn’t want to go. People usually mean well—but it’s exhausting. She admits she, too, has been afraid of saying or doing the wrong thing. She finds the best thing people can ask her (not the person who is with her) is: “Let me know if you need any help.”

What stayed with her were the small acts of dignity: a doctor who introduced themselves, another who made her laugh. I won’t forget her story of the long-haired anaesthetist who, noticing her tears, leaned in and said, “I know, this is shit, isn’t it?” She loved him for that. He saw her as a whole person—not just a patient or a problem. So now, as a doctor, she wants to be that person for her patients, attending to the small things like holding out a hand to say “hello, I see you, I know your name”.

Grace’s own journey offers an alternative to the restitution story which so often shapes our view of illness and healing. Her story is not restricted to physical recovery; it is about joyously embracing life as she is, valuing autonomy over independence (she says for her, independence is a fallacy). It is about being part of a supportive community (I loved her friendships with fellow patients like Rubes, who had crashed his quadbike in Croatia, and Vince, an ex- scaffolder). It is also about fighting for what she believes in (she is a passionate advocate for the disabled community, often appearing on TV and Radio). Arthur Frank might call this alternative story a “Quest narrative” – where illness is not a temporary detour from life, but a meaningful journey seeking purpose, personal growth and connection with others.1

For doctors and medical students, it’s an uplifting and eye-opening read—one that just might change how you see your patients, and your own role in their stories.

Featured book: Grace Spence Green, A Doctor’s Notes on Recovery and Radical Acceptance, Profile and Wellcome Collection, 2025, ISBN 97880084486, £18.99 (Hardback) 213 pages

Reference

Frank, A. W. (2013). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness & ethics. University of Chicago Press.

Featured photo: Andrew Papanikitas, Sidmouth Beach, 2025