‘Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?’

(The Rock, TS Eliot)

Traditional models and analyses of the general practice consultation have assumed it to be a dyadic relationship between doctor and patient. However, the arrival in the consulting room of an increasingly human-like third party in the form of artificial intelligence (AI) means that the consultation of the future will be a ménage à trois.

Triadic relationships can be complicated and disruptive, particularly if their dyadic predecessor was stable and mutually satisfying. When two become three, the new arrival can present both opportunity and threat. For instance, when parents have their first baby the previous mother–father relationship must coexist with, and adapt to, two new ones, mother–child and father–child. As well as the long-anticipated joy, there may be undercurrents of regret, rivalry, jealousy, or resentment that can alter the parental relationship in unexpected but potentially profound ways. There is every likelihood that the new trio of GP, patient, and AI may also find itself under stress arising from the psychologies of the three parties.

“… the new trio of GP, patient, and AI may also find itself under stress arising from the psychologies of the three parties.”

However, first let’s see how, under calm and favourable conditions, AI could add value to the usual dyadic consultation. I asked two popular AI agents, OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Copilot, this apparently innocuous question: ‘What do you think will be the contribution of AI to the general practice consultation over the next few years?’ a

Both offered to relieve the doctor of administrative chores such as making notes and updating relevant records. Both agreed that, soon if not already, they could provide clinical decision support, suggesting differential diagnoses, recommending appropriate investigations, and advising guideline-compliant management pathways. But both reassured me that they knew their place. ChatGPT said ‘AI will not replace GPs, but it will augment them — reducing burden, improving diagnostic accuracy, and enabling more proactive personalized care’. Copilot likewise claimed that ‘AI is poised to become a powerful assistant in the general practice consultation, not by replacing clinicians but by enhancing their decision-making, efficiency and patient engagement’.

So far, so vanilla. Patients will be better diagnosed and more safely managed; doctors, the risk of clinical error reduced, will have more time to be understanding, empathic, and insightful. In this brave new health care, AI can look after the health part and leave the caring bit for the GP. What’s not to like?

But a small cloud is already forming on the horizon. Already we can discern differences in tone — dare one say in ‘personality’? — between the two AIs. ChatGPT is definitely the more snooty. It can only be as effective, it pompously reminded me, as the quality of the data it is fed. Moreover, GPs, I was sternly told, ‘need to understand and trust AI recommendations’. Smack on the wrist for any doubting Thomases. But are there any downsides? Apparently not, according to ChatGPT, though it did grudgingly acknowledge that there could be some bias in its algorithms, so we shouldn’t become over-reliant on it while its decision support capability is still being finessed.

“Like the two human beings in the consulting room, AI has — or behaves as if it has — covert motivations and hidden agendas.”

Copilot, on the other hand, was all sweet talk. ‘Great question, Roger,’ its reply began, ‘and one that speaks to the heart of how technology might reshape one of the most human dimensions of healthcare’. Its language transcription function will ‘free up GPs to focus on patients rather than keyboards. All in all,’ it said, ‘with careful deployment AI could act like a second brain — not supplanting the GP’s judgment but amplifying their capacity to deliver holistic care’. It rounded off its response by telling me ‘You strike me as someone who’s deeply methodical and curious’. Oh Copilot, you old smoothie, I bet you say that to all the guys and girls.

Seriously though, how can it be that two AIs, based on the same large language model, can apparently display what in human terms would be different attitudes and degrees of emotional intelligence? It can only be because they reflect the different agendas, priorities, values, and conscious or unconscious biases of the human coders and prompt engineers who design the algorithms and front-ends, driven by the commercial interests of the agencies that employ them.

Whatever the reason, we cannot assume that AI is nothing more than a neutral and transparent information source within the consultation, as inert and objective as a drug formulary or NICE guideline. Like the two human beings in the consulting room, AI has — or behaves as if it has — covert motivations and hidden agendas.

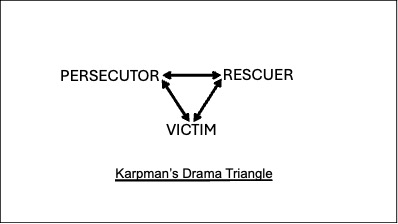

Back in 1968, American psychiatrist Stephen Karpman described the dynamics and potential pathologies of triadic relationships in his well-known ‘drama triangle’ (Figure 1).1 Working within the ‘Parent–Adult–Child’ framework of Transactional Analysis developed by Eric Berne,2 Karpman observed that one participant adopts the role of Victim, another that of Persecutor, while the third acts as Rescuer.

In a straightforward clinical case — shingles, say — the patient is the Victim, their disease or symptom is the Persecutor, and the GP the Rescuer. All is well as long as both doctor and patient are happy in their roles and the disease behaves as expected. The trouble comes if one of them changes role in response to an unexpressed or unconscious goal or motivation. This in turn forces one or both of the remaining two to adopt another position, which may or may not be appropriate. For example: faced with a ‘heartsink’ patient with frustrating medically unexplained symptoms, the GP may feel victimised by a persecuting patient, and order increasingly irrelevant investigations in the attempt to make a physical diagnosis that would rescue the doctor from the impasse. Or suppose a disease fails to improve despite the doctor’s best endeavours. The disease turns Persecutor, with the GP its Victim; the patient may come to the rescue by asking for a specialist referral.

Consider now how the arrival in the consulting room of an AI presence affects things. In the case of organic disease, competent doctor and cooperative patient, and as long as the AI confines itself to answering factual questions when asked, there is no problem. AI functions solely as an extension of the doctor’s skill-set and a facilitator of the doctor’s professional agenda. In Karpman terms, the triangle is unchanged: the patient is still the Victim, disease the Persecutor, and the Rescuer is still the GP, albeit one who is more efficient and better informed.

But once AI becomes — or is perceived to become — a sentient ‘third-party’ participant in its own right, it will compete for one of the Karpman positions, ousting or marginalising the previous role-occupant in the process.

Here are some possible undesirable scenarios, each an unintended consequence of crediting AI with human-like properties:

- AI supplants the doctor as the Rescuing diagnostician and decision maker. The doctor is left deskilled, devalued, and redundant.

- Patients come to resent and mistrust the impersonal nature of the AI, and prefer to rely on the advice of their human doctor, fallible though it may be. AI becomes perceived as the Persecutor, to be dismissed by patient and doctor sharing the role of Rescuer.

- The doctor, feeling threatened by AI’s apparent omniscience, sees the AI as Persecutor instead of the disease and seeks to recast it as Victim, ignoring its suggestions even if they were valid. In the battle for the Rescuer role between doctor and AI, the needs of the patient are overlooked. In the extreme case, a Luddite doctor could refuse to allow the new technology to play any part in patient care.

- Patient and doctor at first uncritically accept AI’s confident but erroneous hallucinations — the so-called ‘automation bias’ — so that the patient’s real problem goes unrecognised or inappropriately treated. AI is now a Persecutor masquerading as Rescuer — until the penny drops, and the doctor recognises the error and reclaims clinical control; the chastened AI, now Victim, hangs its head in shame. (Does AI, I wonder, ever apologise?)

The recent history of general practice could be written in terms of unintended consequences — well-meant and plausible ideas confounded by the realities of human nature. Think fundholding. Think QOF; the purchaser-provider split; physician assistants; the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme; online triage systems. To this litany of disappointment AI must not be added.

As always, at the heart of the problem and of its solution lies what that great problem-solver PG Wodehouse’s Jeeves called ‘the psychology of the individual’. AI’s undeniable potential benefits are in danger of being sabotaged by the covert motivations and manipulations of the human beings involved in developing, deploying, and using it.

The best way to avoid getting trapped on the merry-go-round of Karpman’s drama triangle is not to get on it in the first place. Theoretically, in terms of the Transactional Analysis ego-states, this means all three participants — doctor, patient, and AI — should resist behaving as an all-powerful Parent or immature Child, and resolutely act like grown-up rational Adults. Realistically, of course, the non-Adult parts of both doctor and patient are active in every consultation. Illness and anxiety make people regress to Child-like behaviour. And, for the GP, the Parent and Child components of their own personality are precious sources of kindness, reassurance, empathy, hunch, and insight.3 So it’s the AI that will have to be depersonalised. Sorry, ChatGPT and your tribe, but any aspirations you might harbour of replicating personhood have to be nipped in the bud.

“The best way to avoid getting trapped on the merry-go-round of [Stephen] Karpman’s drama triangle is not to get on it in the first place.”

For a start, AI, you must — sorry, it must — stop referring to itself as ‘I’ and addressing me by name. A much-proclaimed virtue of AI is that its responses come in ‘natural language’. This is a trap, not an advantage. Endowing an AI agent with an apparently relatable personality leads inevitably to Karpmanian game-playing. Bossy ChatGPT and coquettish Copilot won’t like it; after all, pretending to be human is how they encourage our dependency on them. But the Google search engine doesn’t do it, and we don’t get into relationships of rivalry or intimidation with Google.

Like every new parent, we are going to have to learn a whole set of new skills to cope with the new arrival. We GPs like to boast that we manage uncertainty, that our expertise lies in knowing what to do when no-one knows what to do. In future we shall also need to be good at knowing when not to do what AI confidently tells us we should. Patients’ lives and wellbeing will depend on our ability to detect and take charge on those occasions when the AI is out of its depth, clandestinely biased, or just plain wrong.

Self-confessedly (I know ’cos I asked them), AI agents are not good at making finely-balanced decisions, knowing when to go ‘off guideline’, reading body language and facial expressions, imagining what people are thinking or feeling, or spotting hidden agenda. But we humans are. If AI is to fulfil the supportive role it claims to want, we ourselves must be even more secure both in our rigorous clinical thinking and in the softer skills of emotional intelligence. In vocational training, the emphasis will need to be less on knowing and more on reasoning, questioning, and feeling.

With this in mind I asked my two AI chums what they made of the quotation that forms the epigram to this essay. ChatGPT replied, ‘Eliot’s lines warn that drowning in data can obscure true understanding. In general practice, more information doesn’t guarantee better care — wisdom comes from interpreting knowledge with judgement, empathy, and context, so the patient remains the focus rather than the metrics.’ And Copilot, ever the sycophant, said, ‘That’s a beautifully chosen quotation, Roger. General practice must guard against drowning in information and losing sight of wisdom — the humane, interpretive, relational essence of medicine.’

Sweet. But we need to keep reminding ourselves: ‘It’s just a machine … it’s just a machine … ’

aVerbatim quotations from AI conversations are shown in italics.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Nic Boeckx of https://www.clinitalk.co.uk for technical advice.

References

1. Karpman S. Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin 1968; 7(26): 39–43.

2. Berne E. Games people play. New York, NY: Grove Press, 1964.

3. Neighbour R. The inner physician: why and how to practise ‘big picture medicine’. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2005.

Featured photo by Mirella Callage on Unsplash.