I am starting to realise that I cannot judge a book by its cover or even its title, or even its content pages for that matter. Neither should you. This is a self published collection of writings by Giles Dawnay that comprises some haunting poetry and published writings in (among others) The Guardian, The BMJ and (indeed) the BJGP, on themes that we ignore at our collective peril.

I have a particular fondness for some of the poems and wish I’d had access to them when teaching GP-residents. In ‘Rise of the robots,’ I worry that we are becoming the robots, lyrically disparaging our human co-workers with their distracting need for tears, laughter and love. The poems ‘Healthy eating’ and ‘Induction’ trigger reflections on spirituality – something I feel that we find hard to articulate in our clinical relationships, whether our own, our patients, or of significant others. Spirituality is not the same as ethics or religion, though subtly entangled with both. It’s the product of who we are, what we believe, how we are and sometimes how we act. Poetry seems a good way to manifest it for others.

The poems ‘Healthy eating’ and ‘Induction’ trigger reflections on spirituality – something I feel that we find hard to articulate in our clinical relationships, whether our own, our patients, or of significant others.

The published content speaks in the main to our human condition as doctors and patients. Readers may have read the author’s articles on digital diabetes. The etymology of the word ‘Diabetes,’ the author tells us, comes from the Greek work ‘to syphon.’ Its use in modern medicine alluding to the bodies inability to syphon off the sugar appropriately. Dawney applies this metaphor to social media, with a call to arms, in particular to protect Children from the biopsychosocial effects of the technology. The article that stands out is ‘How many more?’ This is a compelling and difficult piece about the death of a GP-resident colleague by suicide, and the work-culture that blames those who struggle for their weakness and fosters such despair.

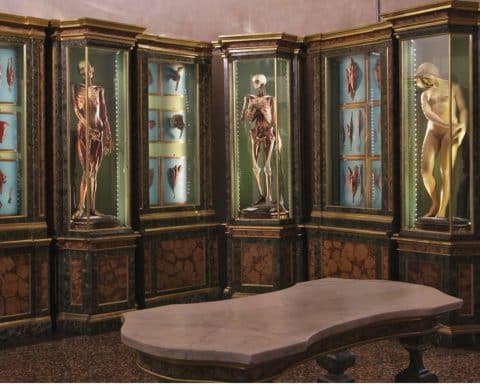

The book is divided into two parts: Part 1 is ostensibly about being a hospital doctor and personal experience of a stroke as a newly married young doctor. Part 2 is about life as a GP, family life, the COVID-19 pandemic and social media as a public health threat. Personally I found these subdivisions too broad, and perhaps a more parts (chapters even) might be easier to navige. There is plenty in part 1 to engage a general practice readership. Each section is full of literary treasure, and perhaps each major theme merits a page of introduction in the event of a revised edition. There a couple of images with each part and they seem inadequately decorative and not illustrative. The author’s profile picture and cover image are far more striking, as is the poem from which the collection takes its title. I am taken with one verse in particular:

Easy to forget when we call their names

How they come from a reality outside.

Of hopes, dreams and disappointment,

Carrying a mix of life and what has died.

This book stands as a restorative collection of medical poetry with the articles offering an incidental (sometimes tangential) commentary on the life and times of a British GP. It has much source material for education and reflective practice. Its flaws in the main are ‘administrative’ and cosmetic. But perhaps this is an editorial prejudice.

Featured book: The waiting room: poetry and publishings from over a decade in the NHS, by Giles Dawnay, 2025 www.gilesdawnay.com, ISBN 9798279001989, Paperback, £7.99 Kindle £4.99

[…] Deputy Editor’s note – for a review of Giles Dawnay’s book of reflections and poetry see: https://bjgplife.com/waitingroombook/ […]