As one of the five pillars of the Islamic faith, the fast of Ramadan is observed by the majority of Muslims across the globe. In the UK nearly 3 million British Muslims refrain from food and drink between dawn and sunset, which in the summer months can be up to 18 hours in duration. In 2020, this will be from 24 April to 23 May, depending on the sighting of the moon. It is considered an obligatory ritual for all healthy adults. Exemptions are given for those who are advised that they will come to harm due to an acute illness or from complications related to pre-existing chronic conditions. We are well into Ramadan but some people may still run into difficulties if they become acutely unwell and have underlying chronic conditions.

RESOURCE: Oxford CEBM Is it safe for patients with COVID-19 to fast in Ramadan°

RESOURCE: Ramadan Rapid Review on British Islamic Medical Association°

Managing acute illness

Muslims are religiously exempt from fasting if there is a reasonable fear that fasting will lead to harm, or if their recovery will be delayed by fasting. Each person would evaluate their circumstance on an individual basis in accordance with the degree of symptoms they are experiencing, and any risks associated with fasting during that illness. Broadly speaking, this is judged on the prior experience of such an illness, common knowledge, and clinical advice.

Patients who have experienced an acute illness… may seek clinical advice about when to restarting fasting.

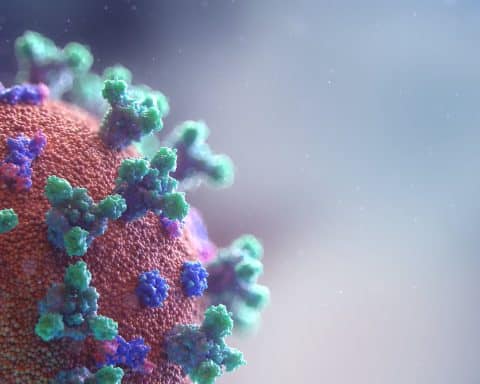

However, patients with a fever and prolonged illness secondary to COVID-19 can become severely dehydrated and are at risk of sudden acute deterioration. As such, these patients should not fast (or should cease fasting) and ensure adequate hydration. Further caution should be applied where other co-morbidities are present. Patients who have experienced an acute illness may resume fasting once they have made a recovery. They may seek clinical advice about when to restarting fasting. This would be dependent on the risk of relapsing into illness, their ability to tolerate the fast, and if their recovery will be delayed by fasting.

Managing chronic conditions

These patients form the bulk of presentations to GPs asking for advice on if they should fast. Medicines optimisation is a key feature of these consultations, as patients are looking to switch regimes that are compatible with non-fasting hours (in the summer months this is usually once-daily dosing). Patients should be risk stratified according to the severity of their condition and advised accordingly. This is expanded on in our guidance,° but is based on clinical discretion considering age, frailty, previous experience of fasting, multiple comorbidities, and any other factors the GP deems important.

If despite all effort patients choose to fast against clinical advice they should still be supported. Patients should remain vigilant in monitoring their health whilst fasting (e.g. blood sugars, blood pressure, weight), ensure adequate sleep, and where appropriate and safe, have their medication regimes adjusted. The importance of hydration in non-fasting hours should be emphasised, as well as patients having a low threshold for breaking the fast if they experience any adverse effects.

Tips for counselling patients who wish to fast against clinical advice:

- Explore their experience of fasting previous years, especially if that had led to an exacerbation of illness, as well as their motivation for fasting against clinical concerns.

- Signpost towards seeking the opinion of a trusted religious authority, if preferred, to reassure them that clinical concern is a valid religious contraindication to fasting. Here they can explore making up these fasts in the shorter winter months. If their condition is severe enough, they may have an exemption from fasting.

- Discuss the importance of medicines optimisation. Focus on the practicability of dosing regimes and the sequalae of events if chronic conditions go out of control.

- Raise the possibility of alternative options: fasting during the shorter winter months (where fasting duration is around 11 hours in the UK), or fasting a few days a week.

Conclusion

Fasting in Ramadan is an individual choice and should be supported through a shared decision-making process. Behaviour change and activation during Ramadan suggests it may also be an opportunity to discuss smoking cessation, weight management, and healthier eating.

It is important that GPs recognise that some Muslim patients can have a very strong motivation to fast in Ramadan, even if they have significant co-morbidities such as cancer or advanced organ disease. Ignoring or being indifferent to this may lead to patients and their families losing trust in their clinicians, and possibly coming to harm from self-management and not seeking further counsel when needing advice. However, if they are sensitively and appropriately counselled, patients can be supported to have a safer Ramadan and gain the spiritual benefits the month brings.