Alistair Appleby is a GP and Honorary Senior Clinical lecturer at the University of Aberdeen. He is on X: @DrAlAppleby

Alistair Appleby is a GP and Honorary Senior Clinical lecturer at the University of Aberdeen. He is on X: @DrAlAppleby

‘Empiricism’ or the ’empirical method’ is central to orthodox medical science. It is the belief that truth is best known by observation, and a particularly careful version of this: the scientific experiment. Empiricism’s force supercharged the 16th century, with Copernicus’ and Galileo’s observations blowing away the former widely accepted view of Aristotle’s that the Earth was the centre of our solar system. The use of empirical science has led to spectacular progress and justifiable trust in the medical field. But to what extent is what we observe through research and scientific instruments a full account of human health, or even of reality in general?

Experts in a particular field of science often seem most open to the finite nature of knowledge in their speciality. Is there any reason to suppose that the human mind, even augmented by AI and sustained by global scientific communities, could come to a full understanding of the universe, or even of that portion of reality that concerns medicine: persons? ‘How can one know that all that can be known is that which is experienced?’ 1

“… to what extent is what we observe through research and scientific instruments a full account of human health, or even of reality in general?”

Not long ago, geneticists considered much of human DNA to be ‘scrap DNA’. In the last 15 years this has been rethought, and much of the genetic material previously understood to be detritus from evolution has been discovered to have important gene controlling and protein building functions that challenge our previous conceptions of clinical genetics.2 Similarly, the role of the gut biome in physical and mental health is in its infancy and could be expected to grow in maturity and influence.3

We must accept that medical knowledge is progressing, and science is still discovering, and therefore our knowledge is incomplete at any given moment. So how are we best to understand the relationship between empirical medical science and what remains to be known, or is perhaps unknowable?

Ram Bhaskar, primary author of critical realism, a scientific philosophy that some believe to be the most credible structure for the human sciences,4 suggests that empiricism has limits that relate to our humanity. Bhaskar claims that ‘[The] concept of the empirical world is anthropocentric.’ 5 In other words: empirical science limits reality to the capacities of human observers.

He suggests that good-quality empirical science is vital but should be viewed only as a subset of reality. For example: the logic of mathematics is not based on observation, but chiefly on rational argument. The first statement of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’,6 is not empirical. Ethical groundings, vital for medical practice, cannot be distilled from observation.

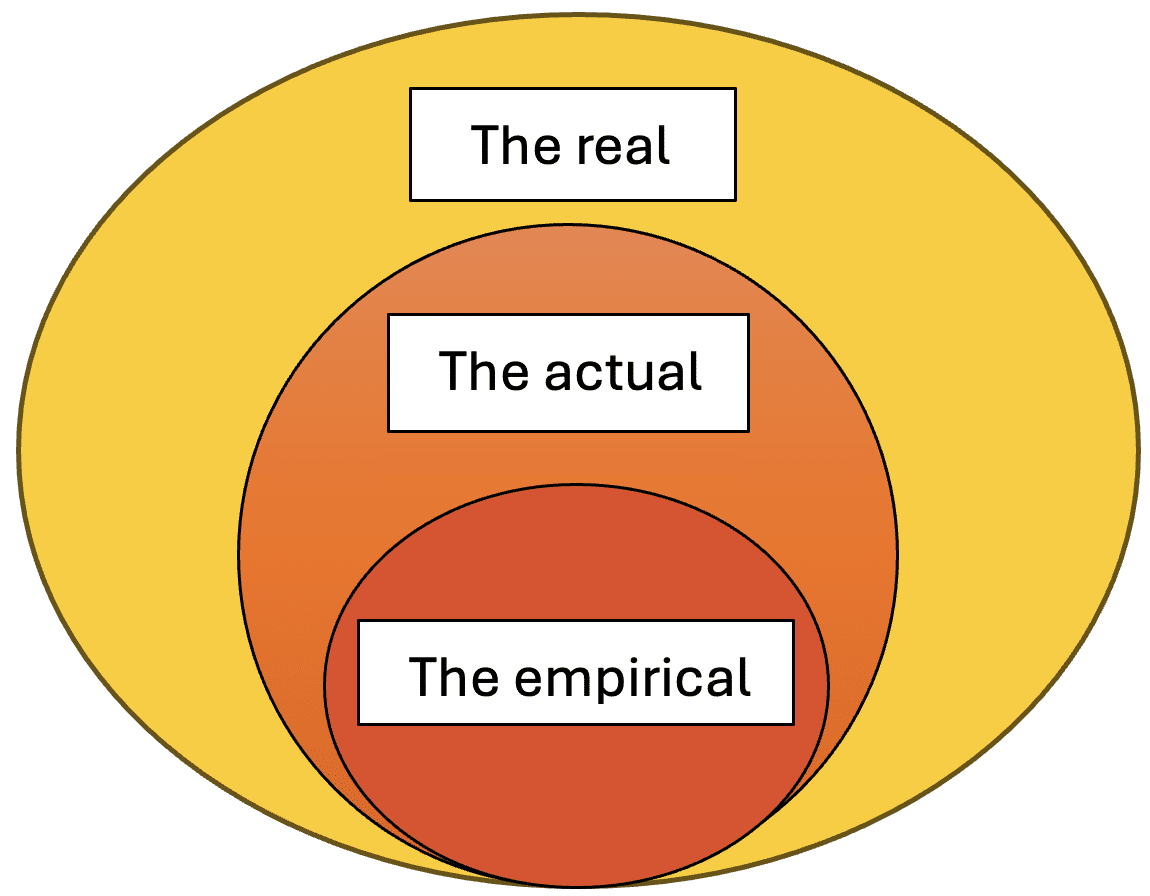

Figure 1 represents critical realism’s conception of the position of empirical science — one which might be useful for medicine.

The ‘real’: mechanisms and materials

We now know a good deal about X-rays but consider the pathway to this knowledge. X-rays, a zone of the electromagnetic spectrum, existed before we discovered them. They are emitted from the corona of the sun, and some naturally occurring radioactive substances. The forces and materials of the universe exist whether known about or not. All that exists, including both the physical matter and the tendencies and forces (often previously referred to as ‘laws’) present in the universe, are referred to in critical realism as ‘the real’. In our example, X-rays were part of this global reality even when undiscovered.

The actual: events

Naturally occurring X-rays had the properties they possess today before humans existed. But, despite having this potential, until the era of humankind they had not penetrated human tissue. When the human era arrived this became an event: something that had the potential to happen, actually happened. At this point in history X-rays had penetrated human tissue but remained unobserved. For critical realists — of all the things that could happen — those that have actually occurred are, logically enough, referred to as ‘the actual’. The forces and materials that are precursors to an occurrence have now resulted in an event.

“… empirical science is in danger of imagining that all that is real is only that portion that has been observed.”

However, at this point, naturally occurring X-rays were not present in large enough quantities to cause inflammation, and the tools were not available to visualise them, and so for a long time X-rays were not observable.

The empirical: experiences

X-rays became empirical when Roentgen and colleagues viewed first the imprint of uninterrupted X-rays, and later the bones of his wife’s hand on a photographic plate. Empirical science observes, either through the senses or ‘sense extending instruments’, only a proportion of events that occur. These empirical forms of knowledge require at least two preconditions. First, that they are observable (they have properties that make them visible, audible, or palpable, or an appropriate detection instrument has been devised). Second, that they are actually observed; there is someone there to receive and interpret the observations. The ’empirical’ is only an observable subset of events.

What does this mean for medicine?

Well, both encouragement and caution. The belief that reality is limited to what can be known by empirical science ‘depends on the reduction of the real to the actual and the actual to the empirical’.5 In other words, empirical science is in danger of imagining that all that is real is only that portion that has been observed. In his famous book on scientific thinking and method, Karl Popper attempts to demarcate science from non-science, but he is repeatedly clear that empirical science does not encompass all truth:

‘Science is not a system of certain, or well established statements, nor is it a system which steadily advances towards a state of finality … It can never claim to have attained truth, or even a substitute for it, such as probability.’ 7

In practice it is unhelpful to dismiss those parts of a patient’s story: historical trauma, a transient neurological event, or the significance of health changes to the patient’s life narrative, if they are not confirmed by our clinical observations or tests. The ’empirical’ is only an observed subset of events. It is entirely justifiable to place special store on careful empirically gained knowledge, but presumptuous to suggest that only those things that are scientifically observable at the present time, or even in the future, have reality or importance. Medical science is a search for truth, but a truth not necessarily limited by observational science. Rather, ‘It is a search for truth determined by a practical end … namely health and healing of human beings’.8

References

1. Hartwig M. Dictionary of Critical Realism. Oxon: Routledge, 2007.

2. Noble D. The Music of Life: Biology Beyond Genes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

3. Hills RD Jr, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, et al. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients 2019; 11(7): 1613.

4. Bhaskar R. The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences. 4th edn. Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

5. Bhaskar R. A Realist Theory of Science. Oxon: Routledge, 2008.

6. United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 2021. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf (accessed 27 Sep 2024).

7. Popper K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: Routledge Classics, 2002.

8. Pellegrino ED. The Philosophy of Medicine Reborn: A Pellegrino Reader. Engelhardt HT Jr, Jotterand F, eds. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

Featured photo by Aleks Marinkovic on Unsplash.

So important! Well said Alistair.

Thankyou!