Peter McCartney is a retired GP.

Aaron Emery was a beef and ham dealer from Marylebone. His son, William, died in 1869 aged only 4 months and 5 weeks after smallpox vaccination. They are both interred in the family grave at Highgate Cemetery in London (Figure 1).

On their memorial it was recorded by the sculptor Mr Mills, that William died from ‘erysipelas coming on after vaccination’.1 I have walked past this grave many times over the years: as a GP and occasional vaccinator it made me ponder. Those feelings became stronger with the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent outbreak of vaccine scepticism, so I decided to investigate.

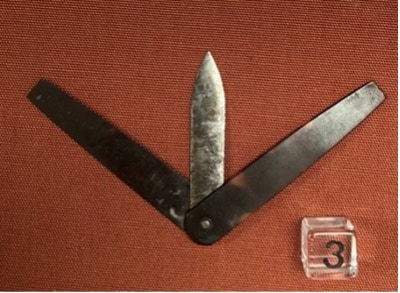

Smallpox was killing 400 000 Europeans per year in the 18th century.2 It must have been great news when vaccination was developed by Edward Jenner in 1796.3 He did this by using fluid from a cowpox blister on the hand of milkmaid Sarah Elmes to produce immunity from smallpox in James Phipps, the 8-year-old son of his gardener. He transferred this ‘lymph’ to James’ arm (Figure 2) using a lancet (Figure 3).

This was an uncontrolled trial with a sample size of one. Perhaps to make up for the small sample size, Jenner challenged the boy with live smallpox(!) more than 20 times (a dangerous procedure for both Jenner and Phipps) to prove immunity.4

Smallpox vaccination became a ‘requirement’ at 3 or 4 months of age in England by the second Vaccination Act of 1853,5 and was provided on an arm-to-arm (child-to-child) basis. It was made compulsory for children, with penalties including fines or imprisonment, by the third Vaccination Act of 1867,5 2 years before William died. Jenner’s vaccine was the first for any disease, and was easily the best available weapon at the time in the war against disease.

I investigated this family using information from: the General Register Office, the British Newspaper Archive, the Wellcome Collection, the Jenner Museum, and various search engines.

“This clinical collusion must have been galling when Aaron knew their diagnosis was inaccurate, and wanted the risks of vaccination to be in the public domain.”

The gravestone implies that Aaron and Rachel had five children (four of whom died under 4 years of age). I have found evidence for six more children in the family (including two born before William), and who I assume outlived their parents.

I can well imagine Aaron’s feelings after William’s death. Anger and sadness come to mind. He would not have had the pride for the loss of a soldier in battle, like the relatives of nearby burials in that cemetery (the only other graves that gave any indication of the cause of the occupant’s death). In Aaron’s case, anger predominates. He had some friction with:

- The vaccinator, George Allen, who was also the GP and the certifying doctor. Aaron wanted vaccination to be mentioned on the death certificate. He brought it to Allen’s house to be altered. Allen then visited Aaron at home, but Aaron was out in his trap. Allen left the certificate unchanged (from ‘erysipelas’).

- Two coroners (Mr Bedford, Westminster and Dr Lankester, Middlesex) who also wanted no mention of vaccination on the certificate.

- The authorities at Highgate Cemetery who did not want ‘who departed this world from the mortal effects of vaccination’ on the gravestone.1

In the end, Aaron prevailed in all these arguments, although he had to compromise on the wording on both the death certificate, which became ‘Erysipelas produced by Vaccination Misadventure’ (Figure 4), and on the headstone. His lobbying had resulted in the exhumation of William’s body, a post mortem, and two coroner’s inquests.6,7

Allen was a GP based in Soho Square. He reported at the inquest that he had been vaccinating for 30 years from the age of 15, doing up to 100 procedures per day. He vaccinated William on 31 May 1869, and reviewed him on 7 June. All four incisions had produced ‘vesicles’, one was large. Allen opened two vesicles that day, to draw off lymph. Two days later there was one large wound (presumably a bacterially infected ulcer). From 9 June until his death on 4 July (just under 5 weeks after vaccination), William was in a coma (‘unconscious’) most of the time. Concerns were raised at the inquest (by Aaron) that another of Allen’s child vaccinees had died in similar circumstances.6

Aaron was a local politician — he became a councillor on Marylebone Council in 1869, the same year William died (a coincidence?), and was still on council duties, inspecting the roads in his trap in the week before he died in 1904, aged 77 years. He was described in his Marylebone Mercury obituary as a man of ‘unswerving rectitude’.8 He reported that he tried to get publicity for this case by writing to national newspapers, but was only successful in local papers.

Nonetheless, in 1871 Aaron was the first non-medical witness called to be ‘examined’ by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Vaccination.9 Their report is an impressive mine of information and includes six pages of his evidence. From his description and history of his son’s illness there, I strongly believe that William died from cellulitis in the vaccinated arm (‘it swelled to twice the size’) which then ‘spread all over his body’ — sepsis, or blood poisoning as Aaron called it. So, in my opinion, Aaron was making a better job of the diagnosis than Allen and the two coroners present at the inquests.7 He reported that Allen made four incisions in the boy’s arm, two more than Jenner’s method (why Jenner made two incisions is unclear and with modern hindsight, unsafe and unnecessary).

“Who knows what the father, Aaron, might have done if he had access to modern information technology?”

Jenner’s smallpox vaccine became the prototype of more than a dozen vaccines that we each routinely and voluntarily benefit from today.10 It had enormous benefits, and a small risk that claimed William’s life. The lancet was literally cutting edge technology at the time — we can see now that it was too early for research ethics, refrigeration, sterilisation of equipment, Florence Nightingale-style hygiene, and (disposable) syringes and needles.

Aaron was an early opponent of vaccination as a result of his son’s death. I suspect that his anger was aggravated by the attempted cover-up. The two coroners wanted to allay public anxiety, avoid an outcry, and keep vaccination rates high. The GP had the same agenda, and also wanted to preserve his professional reputation. This clinical collusion must have been galling when Aaron knew their diagnosis was inaccurate, and wanted the risks of vaccination to be in the public domain.

It was good to know that Allen had 30 years’ experience of vaccinating, but unfortunate to learn that he had started vaccinating aged 15 years. His qualifications and training are unclear — the General Medical Council was formed in 1858, but had limited powers then, and none when Allen started vaccinating in 1854.

Why was William overvaccinated? I strongly suspect that this was to allow harvesting of vaccine by Allen. Both the initial four incisions and the documented harvesting from two vesicles would have increased the chance of bacterial transmission to William, or from William’s own skin into the wound. Vaccination must have been a lucrative business for Allen, and harvesting vaccine should have kept his expenses down.

Erysipelas, a red herring

Erysipelas (‘red skin’ in greek) was known by Edward Jenner to be a vaccination risk.9 In that document, Jenner is quoted by another Marylebone GP: ‘That vaccination directly produces erysipelas, there is no doubt; indeed no vaccine was protective which did not produce erysipelas’. I think that Jenner was describing a typical localised immune response, common with the many vaccines we know today and not known to him then. Jenner was a pioneering researcher I am reluctant to challenge, but I believe that he was using the erysipelas diagnosis incorrectly. Then George Allen compounded that error by using it on William Emery’s death certificate.

Aaron Emery wanted vaccination to be included on the certificate, and in his evidence to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Vaccination he also challenged the erysipelas diagnosis on the certificate. I agree with both these points.

Today, erysipelas is known as a localised bacterial infection of the upper layers of the skin that responds well to antibiotics, as I know well from my own experience as a GP. As I indicated earlier, in William’s case I believe that he developed cellulitis from a bacterially infected incision, which then led on to sepsis. Maybe erysipelas sounded less alarming at that time, and was used as a euphemistic diagnosis to reduce public anxiety?

Resistance to vaccination continues today — the World Health Organization warns that vaccine hesitancy is a threat to world health.11 Stories of patients dying following COVID-19 vaccination in 202412 echo the events affecting the Emery family in 1869. In recent years in the UK, there have been increases in measles and whooping cough cases, linked to falls in measles, mumps, and rubella and pertussis vaccination rates.13,14

Who knows what the father, Aaron, might have done if he had access to modern information technology? He might have become an internet warrior, or a very early conspiracy theorist. He would certainly have been better informed and able to understand the benefits to the community from vaccination, and therefore able to accept the outcome, tragic though it was. His thoughts have had an impact on me, more than 150 years later.

Allen does not come out of this investigation in a good light. If this is typical of GP behaviour at that time, then there was clear evidence of a need for better regulation of GPs. His roguish errors are summed up in Box 1.

| Box 1. George Allen’s list of unsatisfactory behaviours |

|

Summary

William Emery was 3 months old when he received smallpox vaccine in 1869. Five weeks later he died following an infection in the vaccinated arm. His father, Aaron Emery, was angry and suspected a medical professional conspiracy to conceal vaccination as the cause of William’s death. Aaron was correct, but the motives of that conspiracy were mainly honourable — to maintain public confidence in the vaccine. Aaron was also correct in challenging the diagnosis of erysipelas. He was one of the first in a long line of vaccine sceptics — they can be an important part of research scrutiny.

References

1. A curious question. Monmouthshire Beacon 1869; 11 Sep: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0001272/18690911/026/0003 (accessed 17 Dec 2024).

2. Behbehani AM. The smallpox story: life and death of an old disease. Microbiol Rev 1983; 47(4): 455–509.

3. Jenner E. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolæ vaccinæ, a disease discovered in some of the western counties in England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the cow pox. London: Sampson Low, 1798.

4. Reid R. Microbes and men. London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1974.

5. Wikipedia. Vaccination Act. 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaccination_Act (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

6. Bingham D. The poisoned parson & the travelling corpse; more tales of exhumation at Highgate Cemetery. 2020. https://thelondondead.blogspot.com/2020/09/the-poisoned-parson-travelling-corpse.html (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

7. Alleged death from vaccination: important case. North British Daily Mail 1869; 22 Jul: https://britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0002683/18690722/004/0002 (accessed 17 Dec 2024).

8. Aaron Emery, born 1826, died 1904. Marylebone Mercury 1904; 13 Feb: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000957/19040213/096/0006 (accessed 17 Dec 2024).

9. The House of Commons. Report from the Select Committee on the Vaccination Act (1867): together with the proceedings of the Committee, minutes of evidence, appendix and index. London: The House of Commons, 1871.

10. UK Health Security Agency. Vaccination timeline table from 1796 to present. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-timeline/vaccination-timeline-from-1796-to-present (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

11. Razai MS, Chaudhry UAR, Doerholt K, et al. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ 2021; 373: n1138.

12. Hill M. ‘Our daughter should not have died from Covid jab’. BBC News 2024; 23 Aug: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx2g921rd2lo (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

13. UK Health Security Agency. Evaluating the impact of national and regional measles catch-up activity on MMR vaccine coverage in England, 2023 to 2024. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-of-vaccine-uptake-during-the-2023-to-2024-mmr-catch-up-campaigns-in-england/evaluating-the-impact-of-national-and-regional-measles-catch-up-activity-on-mmr-vaccine-coverage-in-england-2023-to-2024 (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

14. UK Health Security Agency. UKHSA encourages timely vaccination as whooping cough cases rise. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ukhsa-encourages-timely-vaccination-as-whooping-cough-cases-rise (accessed 16 Dec 2024).

Featured photo of Highgate Cemetery by Killyleagh Graver. Used with permission.