Yonder: a diverse selection of primary care relevant research stories from beyond the mainstream biomedical literature

For this year’s December issue, I was asked to put together something seasonal or Christmas-related. My usual approach to writing this column is to do a PubMed search using relevant key terms (primary care, general practice, medical education, for example) and screen hundreds of recently published articles for interesting nuggets. For this column, I used ‘Christmas’ as the key search term to see what was out there. I was met with many case studies of conditions with signs akin to a Christmas tree (bladders, skin lesions, and cataracts to name but a few) and an interesting article on the metabolic responses of Christmas Tree Worms to thermal acclimation. In the end, I’ve chosen three articles, two of which are in the BMJ festive issue tongue-in-cheek style, and one with a more sinister bend.

“There was no association between winning the wishbone competition and wish fulfilment …”

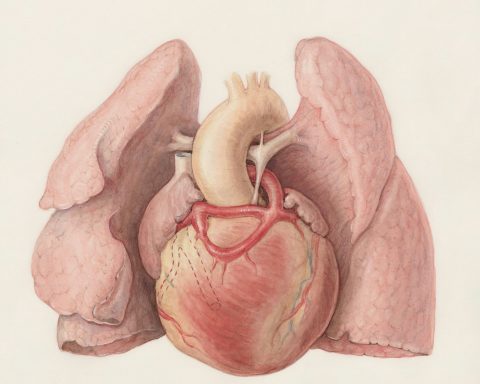

Wishbones

The avian bone commonly known as the wishbone is the furcula, a Latin term meaning ‘little fork’. This bone connects the neck to the sternum and strengthens the thoracic skeleton by supporting the wing strut: it is the equivalent of our clavicle. The first documented use of this bone to try to influence the future dates to the Etruscans around 800 BC in Italy, who would dry chicken wishbones in the sun then gently touch them and make a wish. The Romans turned this practice into a competition akin to today’s ritual breaking of the wishbone, with the victor — the person who keeps the larger piece of the bone — having their wish fulfilled. This study in the US aimed to test the association between wishbone contest outcome and wish fulfilment in emergency department staff.1 There was no association between winning the wishbone competition and wish fulfilment, however, those participants whose wishes were realised reported significantly greater perceived control over wish realisation (relative risk 1.21; 95% confidence interval = 1.06 to 1.40). These results may not be valid in a festive meal setting however, as 3D-printed polylactic acid wishbones were used.

Gifts from patients

Receiving a gift from a patient can present an ethical dilemma for clinicians. In General Medical Council guidance on Good Medical Practice, we are advised not to accept any gifts that may affect or be seen to affect the treatment with provide. The General Medical Services contract requires us to declare any gift from a patient worth £100 or more on a register. Refusing a gift could also affect the doctor–patient relationship if not done sensitively. To help clinicians avoid this potentially challenging scenario, this French study explored the factors associated with receiving gifts from patients and to propose ways to avoid this.2 Being over 40 years old, of the ‘Explorer’ personality type, in the same job for over 10 years, and having a frequent delay of over 30 minutes at the end of a day of consultations were associated with receiving at least one gift from patients. The authors suggest that to avoid unwanted gifts and the subsequent ethical dilemma, clinicians should remain young, run to time, move job every at least every 5 years, and adopt the ‘Analyst’ personality type.

“A timely reminder to us all on social media use: if it’s free, you’re the product.”

Christmas Ozempic advertising

Ozempic, a brand of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist semaglutide, mimics the GLP-1 hormone that has several roles: increasing insulin production in response to high blood sugar levels; slowing gastric emptying; and prolonging feelings of fullness after meals. Originally used in diabetes, it is now widely commercially available for weight management. This study analysed 12 sponsored Facebook adverts for Ozempic from December 2024 using discourse analysis.3 Three interrelated discursive constructs were identified: Santa takes Ozempic; Ozempic as the perfect holiday gift; and medical authority meets holiday cheer. Adverts used cultural symbols like Santa Claus and New Year’s resolutions to construct pharmaceutical intervention as both a necessity and a gift. The authors summarise this dystopian social media advertising landscape perfectly: ‘these marketing strategies mobilize biopower, construct self-surveillance as normative, and contribute to the commodification of health, reinforcing weight stigma under the guise of holiday celebration.’ A timely reminder to us all on social media use: if it’s free, you’re the product.

References

1. Loevinsohn G, Wizda CN, Glynn TR, et al. Christmas break: predictive value of holiday avian wishbone traditions among frontline healthcare workers in a prospective trial. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2025; 18: 1387–1396. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S509590

2. Richier Q, Fey D, Kelly MK, et al. How to avoid gifts from your patients after the Christmas holidays? Rev Med Interne 2024; 45(12): 744–749. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2024.11.015

3. Joy P, Bessey M, Mann L. “I believe in Santa Claus” and Ozempic: a Foucauldian discourse analysis of holiday health advertising. Qual Health Res 2025; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323251350876

Featured photo by Tijana Drndarski on Unsplash.