Yonder: a diverse selection of primary care relevant research stories from beyond the main stream biomedical literature.

Principlistic equality

Principlism in biomedical ethics postulates that clinicians can approach ethical issues by considering four prima facie obligations: respect for autonomy; non-maleficence; beneficence; and justice. A key concept is that these principles are non-hierarchical and context dependent, with no one principle being always more important that another — principlistic equality. However, in specific scenarios clinicians may have to decide which principle should take priority. This survey study in the US assessed how clinicians weighed the comparative importance of the four ethical principles in practice by asking participants to allocate 100 ‘importance points’ across the four domains.1 Just under half (48.1%) of responders endorsed principlistic equality, assigning equal weighting to all four principles. For the remaining participants who endorsed some degree of hierarchy, the principle most frequently assigned a higher value was non-maleficence, followed by autonomy. How this might affect individual clinician’s practice requires further exploration.

Rejected referrals

For a healthcare system to function, there needs to be effective collaboration between primary and secondary care. Acting as a gatekeeper to specialist services is a challenging but important part of the role of a GP. However, there are reports of an increasing proportion of referrals from GPs to hospitals being rejected and returned. In Denmark, hospitals employ GPs as ‘liaison officers’ to facilitate communication between primary and secondary care and improve patient pathways. This study aimed to explore the causes and consequences of referral returns from the liaison officers’ perspective.2 These GPs felt the increase in returned referrals was driven by four factors: increased specialisation of care; standardised pathways that do not accommodate complexity; resource constraints; and economic incentives for hospitals to shift healthcare tasks to primary care. This quote tells a familiar story: ‘It is increasingly difficult to refer patients with non-specific symptoms; those who fit a standardised pathway benefit, while the complex patients risk repeated rejections.’

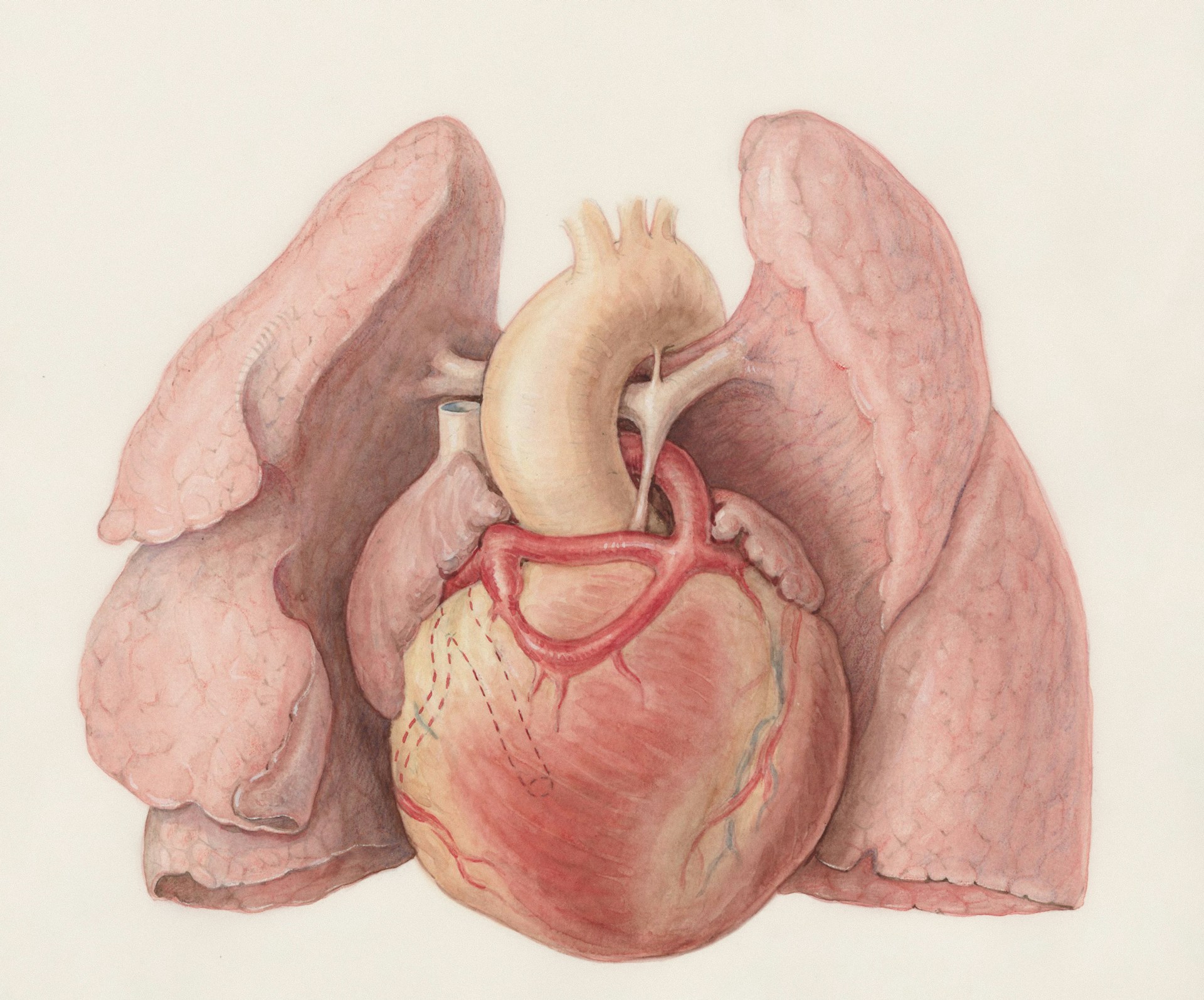

Ruptured AAAs in out-of-hours

A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) is a life-threatening condition requiring immediate surgical treatment, with early recognition key to improving chances of survival. This can be challenging, however, as not only is rAAA uncommon, signs and symptoms are often non-specific and mimic other conditions. In the Netherlands, rAAA is the second most frequently missed diagnosis reported as a serious adverse event in out-of-hours primary care (OOH-PC) behind acute coronary syndrome. This case-control study aimed to identify characteristics associated with missed or delayed diagnosis of rAAA in OOH-PC.3 There were 20 rAAA cases over a decade from 2013–2023 across three OOH services, matched with 80 controls presenting with similar symptoms, usually abdominal or back pain. Compared to controls, several features were more common in rAAA cases: onset of pain <12 hours ago; sweating; patient expressed concern; and calling at night.

Kickstart patient movement

Physical inactivity contributes to one in six deaths in the UK, equivalent to smoking. An estimated 40% of long-term conditions could be prevented if recommendations on physical activity were met at a population level. However, GPs have reported a lack of training or confidence in initiating conversations on this topic. This study provides a five-step framework to guide primary care clinicians in supporting inactive patients to increase their physical activity levels:4 1) assess readiness to change and current physical activity levels; 2) screen for relevant risk factors and contraindications; 3) use key principles to agree on a tailored programme; 4) give advice to reduce sedentary behaviour; and 5) arrange a follow-up consultation. It’s worth reading the full text for further information on each of these steps. The authors also signpost to the consultation guides available from Moving Medicine: https://movingmedicine.ac.uk.

References

1. Scotch HT, Baugh CM, DeCamp M, et al. Principlistic equality: the relative importance of the four principles among primary and urgent care clinicians. Am J Bioeth 2025; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2025.2554766.

2. Kjær NK, Elkjær M, Ibsen H, et al. Causes and consequences of rejected or returned referrals from general practice. Dan Med J 2025; 72(9): A01250002.

3. van den Dries CJ, Dongelmans DA, van der Laan MJ, et al. Characteristics of patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm who contacted out-of-hours primary care: a case-control study. Int J Emerg Med 2025; 18(1): 163.

4. Rooney D, Heron N, Gilmartin E. Kickstart patient movement: a 5-step framework for primary care clinicians to support inactive patients in becoming more active. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2025; 11(3): e002774.