Clare Ellison is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and strategically with the North East and North Cumbria Provider Collaborative; committee member, British Dietitic Association (BDA) ARFID Sub-Group.

Ursula Philpot is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with ARFID, and committee member, BDA ARFID Sub-Group.

Sarah Fuller is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with ARFID, and committee member, BDA ARFID Sub-Group.

Angharad Banner is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with ARFID, and committee member, BDA ARFID Sub-Group.

Paola Falcoski is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with ARFID, and committee member, BDA ARFID Sub-Group.

Mala Watts is an advanced eating disorder dietitian working clinically with patients with ARFID, and committee member, BDA ARFID Sub-Group.

Anna Greenham is a practising GP with lived experience as a carer of a young person with ARFID.

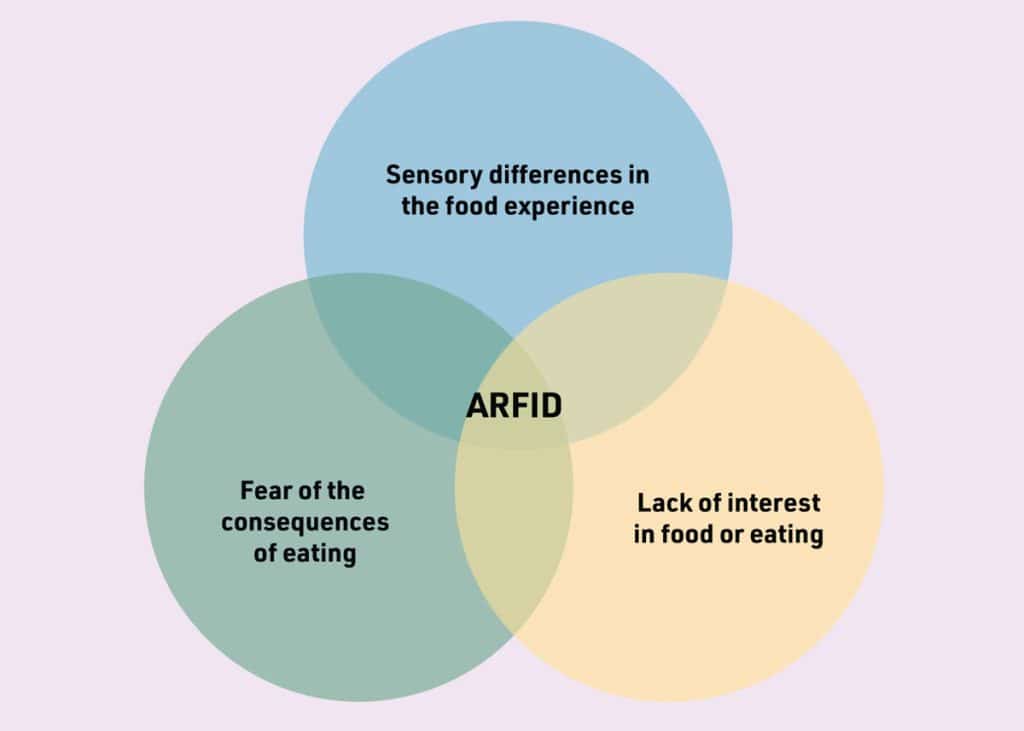

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a classified eating disorder diagnosis with criteria outlined in both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition and International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision. A diagnosis of ARFID should only be made by an adequately informed multidisciplinary team. ARFID is best understood as per the Venn diagram in Figure 1. Most of the time, a person struggling with ARFID will have more than one presentation. The potential signs of ARFID that may present in clinic are:

• avoidance of whole food groups or sensory-specific food categories;

• disgust response to foods/categories (for example, gagging or retching);

• having a diet that is extremely limited to (usually less than 10) ‘preferred/safe foods’;

• lack of interest in eating or missing meals completely (not feeling hungry);

• avoidance of social food settings or environments (for example, unable to eat outside of the family home);

• negatively impacted physical health status including reported weight loss, lack of growth, or symptoms consistent with nutritional deficiency;

• needing to take supplements to meet their nutritional needs; and

• sudden phobia or anxiety impacting food intake.

Understanding ‘picky eating’ versus ARFID

‘Picky eating’ exists as a continuum from disliking a few foods to significant restriction and avoidance. ARFID is the clinically diagnosable and severe end of this spectrum. The eating restriction and resultant physical impact is such that it has a significant detrimental impact on the quality of life of those affected (and their families). ARFID does not occur exclusively in low-weight status, and it is important to recognise that significant nutritional deficiency can also occur in average and above-average weight individuals. Common associations include:

• autism spectrum disorder,1 where the avoidance of foods often stems from sensory specificity (however, not all individuals with ARFID have autism and not all autistic individuals have ARFID);

• chronic history of food avoidance (such as long-term sensory specificity, which has worsened over time); and

• acute onset of food avoidance, for example, a sudden restriction of foods secondary to phobia (such as vomiting, choking, or contamination resulting from phobia/trauma), which may require access to urgent care.

“Box 1 presents resources for signposting and further continued professional development.”

ARFID is not anorexia nervosa

ARFID differs from anorexia nervosa (AN) in that the avoidance is not driven by concerns regarding weight and shape. Any individuals presenting with suspected AN should be referred to the appropriate local eating disorder service.

Initial primary care assessment

The initial assessment of a person presenting with suspected ARFID should focus on:

• a brief history of the presenting difficulties (including current range of foods eaten and psychosocial impact), chronicity, and the patient’s understanding of their food avoidance;

• exploration to rule out differential diagnosis of AN, cultural sanction, or food availability;

• a brief medical history to understand if there is, or may be, a physical cause for the avoidance that may either explain the avoidance or require further medical investigation;

• a physical assessment checked against the Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED) guideline2 with historic measurements of weight and height, to assess the impact on expected growth and development. For autistic individuals, compliance with physical investigations can present an additional challenge. Professionals may therefore need to be more creative or offer subjective assessment based on clinical experience;

• in younger children, an assessment of the characteristics that may indicate paediatric feeding difficulty. Where this applies, referral for paediatric feeding assessment/support is likely most helpful; and

• where there is evidence of physical symptoms (such as gastrointestinal disturbance or abdominal discomfort), which may impact on appetite, interest in eating, or food aversion, these should be investigated first as part of important differential diagnostic exclusion.

“ARFID is considered to be a treatable condition, though instances of relapse may occur.”

Available assessment tools

The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust also have short ARFID screen questionnaires that can help inform initial assessment available from: https://mccaed.slam.nhs.uk.

Assessing physical risk

All eating disorders, across all ages, share the same framework for assessing medical risk: the MEED guideline. MEED is essential in ARFID and helps to inform where referrals meet an urgent clinical risk or may require urgent medical attention.2

First contact with families

Individuals and families presenting to primary care are likely to feel anxious and concerned, and may have had previous experience of feeling unheard, judged and criticised, or blamed. Through personal experience, this is the most common negative complaint received of services. It is important that you offer an empathetic and validating response to their reported challenges.

Offering hope and treatment referral

ARFID is considered to be a treatable condition, though instances of relapse may occur. However, it is highly individual, heterogenous, and can be complicated by factors such as autism, sensory processing disorder, anxiety, visceral/interoceptive difficulties, and other health needs. Therefore, an individualised formulation and care plan is needed for every patient. Evidence-based therapies are still under development. A review of the current evidence base was published in January 2024.3

In view of this, it can be difficult to outline the specifics of a care package. However, dietitians are adequately skilled and well placed for the nutritional assessment and management of those with ARFID.4 Treatment pathways for ARFID vary nationally and can include community teams, acute teams, mental health teams, and eating disorder teams, depending on presentation and risk. Third- sector organisations and other support agencies can also be included depending on local availability, remit, and risk. It is important that you understand your local-area referral process, including which service(s) support treatment, and any associated age-related access and severity indices required to meet criteria. Box 1 presents resources for signposting and further continued professional development.

| Box 1. Signposting for patients/families, and further CPD |

|

| ARFID = avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. CPD = continuing professional development. |

References

1. Kozak A, Czepczor-Bernat K, Modrzejewska J, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food disorder (ARFID), food neophobia, other eating-related behaviours and feeding practices among children with autism spectrum disorder and in non-clinical sample: a preliminary study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20(10): 5822.

2. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders: guidance on recognition and management. 2023. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr233-medical-emergencies-in-eating-disorders-(meed)-guidance.pdf (accessed 23 May 2024).

3. Willmott E, Dickinson R, Hall C, et al. A scoping review of psychological interventions and outcomes for avoidant and restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Int J Eat Disord 2024; 57(1): 27–61.

4. Banner A, Falcoski P, Knight C, et al. The role of the dietitian in the assessment and treatment of children and young people with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). 2022. https://www.bda.uk.com/static/3d62ac89-2837-46fb-987ae870b4b2a617/BDA-ARFID-Position-Statementlogos.pdf (accessed 8 Jul 2024).

Featured photo by AbsolutVision on Unsplash.