There are important medical lessons hidden in Tara Westover’s memoir ‘Educated’.1 The book recounts the author’s upbringing in rural Idaho, raised by religious fundamentalist parents who lived almost entirely off-grid, shunning mainstream education and modern medicine. When the children broke bones or fell sick, Tara’s mother Faye provided herbal and homeopathic remedies. There were some close brushes with mortality: road traffic accidents, head injuries, a major burn with subsequent infection. Despite the total absence of conventional healthcare, the family members recovered repeatedly from injury and illness.

Particularly in a primary care setting, many of the illnesses we see are self-limiting in nature: viral coughs, episodes of labyrinthitis, eruptions of pityriasis rosea. We nonetheless should avoid conflating self-limiting illness with minor illness – many life-limiting conditions will get better with time alone. Multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia, for instance, follow a natural history of relapse and remission.

When her child’s fevers eased, Faye took this as proof that her tinctures had enacted a cure. The same false attribution happens whenever we give nitrofurantoin to patients with acute-on-chronic confusion, treating for a UTI on often scant evidence. Dementia follows a fluctuating course, and periods of confusion will naturally be followed by periods of relative lucidity, so the antibiotics will appear to work even if no infection was at play. Natural remission is mistaken for an intervention effect. Repeat this process a few times, and well-intentioned relatives are soon seeking antibiotic scripts every time their loved one seems more muddled.

The same process is at work when the ward doctor is called to review a hypertensive patient and gives a one-off dose of amlodipine. The blood pressure is rechecked an hour later, and it seems that the amlodipine has done the trick – when of course the blood pressure has simply regressed to the mean, long before any drug effect would be pharmacokinetically feasible.

Looking across the span of human history, effective therapeutics did not emerge in any meaningful sense until the 20th century.

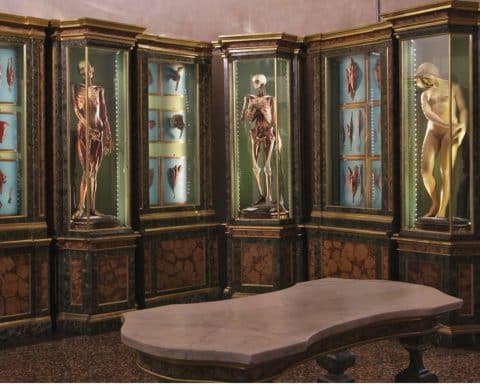

Looking across the span of human history, effective therapeutics did not emerge in any meaningful sense until the 20th century. Physicians have nevertheless managed to occupy positions of prestige and authority for millennia, long before their treatments had any serious claims to efficacy. A tenth century physician might have advised bloodletting for a patient suffering with sciatica, finding that the pains were much improved after a few weeks of venesection.

As doctors we have an inveterate urge to intervene, but much of what we do in daily clinical practice differs little from the herbal remedies of the Westover family, or the bloodletting practices of medieval physicians. Often all we do is open the door to iatrogenic harm. We find that people with mild depressive symptoms feel better after a few weeks on an SSRI – which they probably would have done in a similar timeframe, with or without a tablet. Similarly, we find that infant reflux appears to improve when we give hydrolysed formula or omeprazole – forgetting that physiological reflux will tend to improve over the first year of life regardless of our interventions. This cognitive bias sustained public faith in the medical profession long before doctors had the tools to truly alter the course of an illness. These forces did not disappear the moment that working therapeutics arrived – meaning we remain enthralled by own salves and tinctures, blithely believing in our own powers whilst nature effects a cure.

Reference

Tara Westover, Educated, Windmill Books; 1st edition (1 Nov. 2018), ISBN 978-0099511021, 400 pages, £10.99 (paperback)

Featured Photo by Matt Briney on Unsplash