Laura Heath is a GP and Wellcome Doctoral Fellow at the University of Oxford. She is on Twitter: @laurahheath

Sheena Sharma is a GP Partner and Associate GP Dean, Thames Valley. She is on Twitter: @Sheena1Sharma

Prit Buttar, a retired GP from Scotland, made headlines when in January 2022 he described what drove him to break COVID-19 lockdown social distancing rules after he met a grieving widow (Mrs O) at a vaccine centre in Annan, Scotland.

‘She had dealt with his death and funeral arrangements alone, so I decided to break the rules about social distancing. I leaned forward in my chair and put my arms around her. She clung to me and wept, and sobbed into my shoulder and said “this is the first time anyone’s embraced me since he died.”‘1

We all recognise this instinct, to listen and embrace a person grieving. Yet, in amongst the routine of clinical life, between repeat prescriptions, letters, complex comorbidities, and adapting to remote consulting, doing this well can be challenging. This article aims to move beyond the biomedical ‘stages’ of grief and provide real-world consultation ‘tools’ that can be used to navigate this potentially difficult space.

Bereavement care

Clinicians are often concerned at the lack of time and primary care team resources available to engage with bereaved patients. Bereavement care is viewed as demanding not only on time, but also on the emotional resources of GPs and nurses. With no ‘treatment’ available for the pain of bereavement beyond active and supportive listening, grieving patients may instil feelings of powerlessness in clinicians.2

There is little education for GPs on how to manage this,3 although we recognise many experienced clinicians have already developed skilful techniques from clinical experience and perhaps personal tragedy or literature and film.4

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this problem, with record numbers of bereaved people struggling to find support with grief in the community.5 As people were not able to be with loved ones at the time of death and funerals were limited, typical rituals important in the grieving process were missed.6

Introducing the toolkit

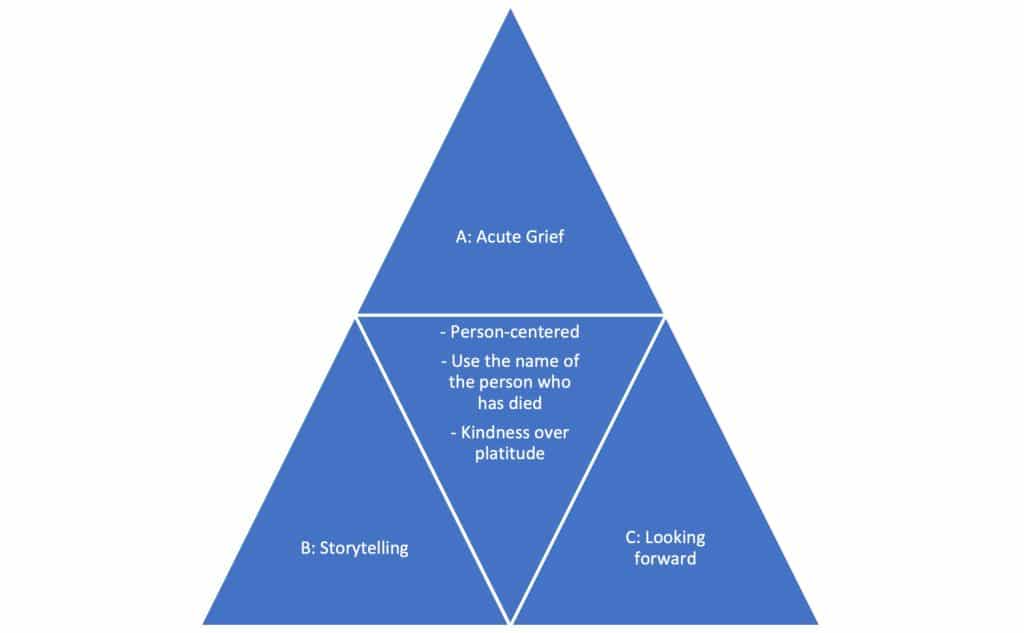

We propose a toolkit that highlights three grief ‘points’, and ‘tools’ that may be used at each of these points (Figure 1). The word ‘point’ was chosen over ‘stage’ or ‘phase’ to remove chronological assumptions, recognising that each person has a unique experience of grief.

Point A illustrates acute grief. This may be the initial consultation, but equally may represent subsequent time points, recognising the variability of grief.

Point B represents a point of reflection and the tools described here facilitate storytelling.

Point C is a point for more mature grief, where the future is emerging. The person may fall between point A and B and benefit from tools described at each point. The toolkit is intended to be iterative and flexible, with patients potentially oscillating between points over time.

At the centre of the toolkit, we incorporated tools that are universally important. These include referring to the person who has died by name, as a sign of respect, and to normalise and facilitate talking about their grief. To choose kindness over platitude when discussing bereavement.

Platitude tries to minimise distress, and says ‘at least this is all over’ or ‘they have gone to a better place’. Kindness meets the person where they are, holds suffering, and says ‘I can see this is really hard, I am sorry this is hurting you’. Throughout the toolkit we recognise that each person’s experience of bereavement is unique. The skilled clinician will hold the tools lightly, be prepared to deftly switch between tools, and individualise each consultation.

This is not a biomedical guide and does not seek to describe management of conditions that may be associated with or develop in parallel to the experience of grief (for example, depression, prolonged grief disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder), which should be considered at every point. Rather, this article hopes to equip the clinician with options to reach for when there is a feeling of powerlessness in the consultation, and help teach techniques that fit with more modern understandings of grief.7

Point A

At point A, the acute phase, much as Buttar illustrated, allow negative emotions to fill the encounter, free of judgement. Providing this space for the person to grieve freely may not be accessible to some people and it is important for the individual to express their grief. Holding this distress may be all that is required of the initial consultation.

Normalise the need for support. This could be encouragement to talk about the person who has died with family and friends (if able), or ongoing medical support with follow-up. Primary care is ideally situated to provide this continuity of care, and we suggest this is particularly central to bereavement.8 Time off work and medication could be offered as options if appropriate. There are many excellent charitable organisations that provide support to people and we list some of these in Box 1.

Box 1. Resources for those who are bereaved

|

Rituals around death are important aspects of grief in most cultures.9 These are diverse but could include time around the dead person, funerals, managing remains, flowers, and visits from relatives. More personal rituals could include collection of items for a memory box. Ask what these are, bearing in mind that some of these may have been disrupted because of COVID-19.10 Explore what rituals are important to the person who is grieving and encourage participation where able.

At this point it may be appropriate to use one or two supportive phrases, such as ‘I can see that you are in a lot of pain right now, it may not improve, but you will learn ways to live with it’. We suggest avoiding the use of ‘try to cheer up’ or inferring that this is something that they will recover from.

Point B

As grief progresses, talking and telling stories about the person who has died may become more important. Listening at this stage could include:

• allowing space for people to describe memories or stories from the past;

• talking about their relationship with the person and what has been lost; and

• what was the person who died like? Share a photo?

Simplify questions to make them more manageable. For example, ‘How are you right now?’ As opposed to the all-encompassing, ‘How are you?’. Some people may feel guilt over their grief, perhaps that they are not grieving enough. Introduce and normalise the concept of a rest from grieving. Metaphors or analogies can be used effectively when reflecting on emotions and events that have occurred. An example could be ‘the last full stop does not define the meaning of the book’, if there was suffering at the end of life.

Literature as a prescription can be used; to give words and meaning to a person who is perhaps struggling to express or comprehend the depth and breadth of their grief. Poetry in particular can also provide comfort to the person in that they are not alone in their grief. We make poetry suggestions in Box 2. Alternatively, others find community activities such as sponsored walks can create positivity from loss by bringing people together.

Box 2. Poetry suggestions for bereavement

|

Point C

At point C some time will have passed since the person died. Continue to talk about the dead person by name, even years after death and in unrelated consultations. Explore again whether the grief is ‘abnormal’ and the person may need more intensive psychological support and onward referral.

Consider how societal views about a particular bereavement may affect the individual (expectations about level and duration of grief for the death of a child or elderly relative, for example), and how this may be very different to what the particular individual is experiencing. Explore the effect this may have on them. Hold your own assumptions about what grief should look like, or your own experiences of grief at arm’s length.

Gently work towards moving forwards, acknowledging that grief and pain may not improve but that one will learn how to live with it. Discuss trying not to hold grief so tightly they cannot embrace the future. Possible questions could include:

• ‘What would (name the person who died) want for you now?’

• ‘How would (name the person who died) want you to be living?’

These can be used as openers to enable the person to reflect on where they are now, and where they would like to go.

Application

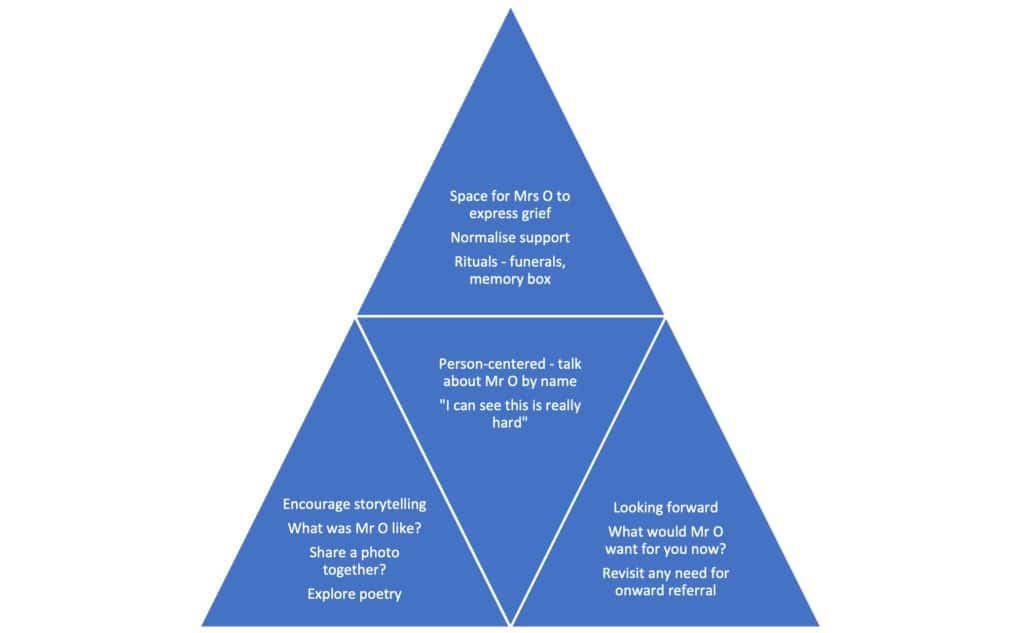

Every iteration of the toolkit will rightfully look different. To illustrate one possible example, we have extrapolated the scenario of Mrs O and Buttar in the introduction in Figure 2.

Summary

The toolkit we propose moves beyond a linear understanding of bereavement and grief. We describe not stages (assuming progression) but points in grief that may or may not be revisited. Well-managed grief has the potential to both reduce the risk of complicated grief with the associated morbidity, and create a real sense of reward in our work as clinicians.

References

1. Feerick K. Scots doctor who broke covid rules to cuddle grieving widow left outraged by No. 10 parties. Daily Record 2022; 17 Jan: https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/scots-doctor-who-broke-covid-25958186 (accessed 24 Mar 2022).

2. Pearce C, Wong G, Barclay S. Bereavement care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Gen Pract 2021; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp21X715625.

3. O’Connor M, Breen LJ. General Practitioners’ experiences of bereavement care and their educational support needs: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ 2014; 14: 59.

4. MacFarlane A. A case of grief: SAPC prize winner. Br J Gen Pract 2021; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp21X717245.

5. Harrop E, Goss S, Farnell D, et al. Support needs and barriers to accessing support: Baseline results of a mixed-methods national survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2021; 35(10): 1985–1997.

6. Boland MJ. A hard time to die: grief and the coronavirus: Michael Boland. Br J Gen Pract 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X710513.

7. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999; 23(3): 197–224.

8. Heath I. COVID-19 and the legacy of grief. Br J Gen Pract 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X712181.

9. Pace JC, Mobley TS. Rituals at end-of-life. Nurs Clin North Am 2016; 51(3): 471–487.

10. Selman LE, Chamberlain C, Sowden R, et al. Sadness, despair and anger when a patient dies alone from COVID-19: a thematic content analysis of Twitter data from bereaved family members and friends. Palliat Med 2021; 35(7): 1267–1276.

Featured photo by Alex Dukhanov on Unsplash.