Hilde M Buiting is a senior researcher at Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and the University of Amsterdam.

Hilde M Buiting is a senior researcher at Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and the University of Amsterdam.

Gabe S Sonke is a medical oncologist and professor of clinical oncology at Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and the University of Amsterdam.

This article depicts a reflection about developments in medicine over the past years through which the fighting narrative within cancer (and medicine in a more broader sense) transformed from its negative stance, represented as inappropriate care, towards a positive stance, represented in a healthy fighting culture. Before we focus on what can be considered a healthy fighting culture, however, we first look back on medical developments in medicine, generally speaking.

| Highlights |

|

Developments over time

During the 1970s, although medical practice had already started to change, Ivan Illich was one of the first who openly developed a critique against medicalisation, with particular emphasis on overtreatment in the last phase of a patient’s life.1

“Illich’s work can be regarded as the start of a discussion in how to prevent overtreatment in the last phase of a patient’s life.”

Illich’s work can be regarded as the start of a discussion in how to prevent overtreatment in the last phase of a patient’s life. Inspiring discussions about the assessment of (in)appropriate care followed since this assessment encompasses much more than the assessment as to whether patients received anti-cancer therapy a couple of days before death. Since then, the discussion developed and retrospective medical record studies increasingly reported about the frequency of patients who had received some form of systemic anti-cancer therapy 5, 10, or 30 days before the patient’s death, which are being perceived as quality indicators of possible overtreatment.2–4

While these discussions surrounding (in)appropriate care in the last phase of a patient’s life continued, another change in medical practice seemed to have arisen through medical progress too.5 Instead of one or two lines of anti-cancer therapy, patients with stage IV disease could sometimes be treated with anti-cancer treatment while having stage IV disease for more than 10–20 years with relatively few side effects.6 Although these trends differ across cancers, discussions about (in)appropriate care in this disease stage started to be approached differently, that is, not as a patient with limited life expectancy anymore. Despite the fact that those patients were almost all having an incurable form of cancer (with stage IV disease), they wanted to continue living and fight for their life. This is an important difference, since the negative fighting narrative (that is, receiving aggressive treatment in the last phase of a patient’s life) to a certain extent disappeared because treatment was less burdensome and more effective (substantial life prolongation) when compared to 20 years ago.7

As a result, medicalisation, which became an important topic of debate during the 1970’s representing possible overtreatment, thus slowly changed into something that goes along with positivity too. Apart from making associations with aggressive treatment, medicalisation now also represented innovative, less burdensome treatment options to be able to live longer in relatively good health. This paradigm shift has important consequences for the discussion surrounding medical futility and appropriate care.

Apart from the discussion of finding an appropriate balance of quality and quantity of life, which is particularly important among patients with limited life expectancy, the discussion to a certain extent transferred towards dealing with the costs of expensive treatment regimen. One important solution to tackle this cost issue is reported by van Ommen-Nijhof et al, who provided options to limit the impact of expensive anti-cancer therapy by using drugs more efficiently. By using less (and/or in different combinations) of the drug its clinical efficacy could still be maintained, but in a much more cost-effective way.8,9 Apart from a patient’s own desire to fight for life while having cancer with reasonable life expectancy, finding options to make available new treatment regimen as cost-effective and least burdensome as possible provide indications that fighting in the context of anti-cancer therapy can nowadays be approached in a much more positive way.

So, while medical progress makes a healthy fighting culture more easily achievable, we would like to argue that we need to go ‘beyond critique of the [negative] fighting narrative’ 10 and look for ways in which patients’ and their families’ intrinsic drive to ‘fight’ and ‘live’ with incurable cancer can be positively interpreted.

“… we found that speaking about [patient’s] presumed battle against cancer was immediately associated with negative associations with the ‘war on cancer’.”

Chronicity and an intrinsic drive to live

Living with incurable cancer and experiencing cancer as a ‘chronic’ disease characterised by lighter and less intensive treatment, contrasts with an article by Antonaccio (2020) in which she, as a social science researcher and cancer survivor herself, embodies patients’ frustrations and the potential tension of the ‘fighting’ culture they often found themselves in.11 In this article, she described how she changed after being diagnosed with cancer as a child, 15 years ago. She described how aversion to the idea of mortality developed into the idea that surviving cancer should be regarded as a battle and a will to fight.

Her story is a classic example of the ‘old’ perspective of medicalisation/aggressive overtreatment as described above. One important criticism about this ‘old’ fighting narrative is that showing a positive fighting spirit should not be regarded as the standard attitude by patients. In fact, this could sometimes result in an unhealthy fighting spirit, for example, a burdensome fight for themselves.12 Another criticism for having a fighting spirit to combat cancer is that such a spirit may enforce the provision of treatment at all costs. The study by van Ommen-Nijhof et al 8 at least shows that concerns surrounding costs can to a great extent be lessened by using drugs appropriately, making the discussion surrounding appropriate care and treatment a more positive one.

In our previous interview study with 29 patients with some form of incurable cancer, we found that speaking about their presumed battle against cancer was immediately associated with negative associations with the ‘war on cancer’.10 Interestingly, the patients we spoke with to a great extent seemed to show a healthy, intrinsic fighting spirit themselves (for example, they were having a positive attitude, wanted to continue living, and were glad with the anti-cancer treatment they had received). Yet, talking about fighting cancer itself primarily brought along negativity.

This is to a great extent in line with the literature surrounding this topic, which is often negative and one-sided. There thus seems to be a large difference between talking about fighting cancer and observing how patients indirectly seemed to fight themselves by showing their intrinsic fighting drive. Patients often looked for new treatment options, insisting to finish a treatment-course. In plenty situations, it could be argued that such a battle can be regarded as appropriate care. We therefore feel that such an intrinsic drive can easily go along with a ‘healthy fighting culture’ and argue to go beyond critique of the fighting narrative.10

In philosophy, it is generally agreed that in the definition of appropriate care (or related terms, such as medical futility,13,14 overtreatment,15 or [in]appropriate care16,17) it is often the patients’ perspective that eventually guides this judgement. In other words, ‘none of these effects [of treatment] is a benefit unless the patient has at the very least the capacity to appreciate it.’ 14

We propose a definition of a ‘healthy fighting culture’ as a culture in which patients (either alone or together with significant others) strive for optimal wellbeing for as long as possible. This may sometimes encompass heavy (but effective) anti-cancer treatment during specific time periods. At the same time, it may also encompass situations in which treatment is, in certain instances, purposefully withheld or withdrawn: patients not only fight for life, but also for their wellbeing.

Healthy fighting

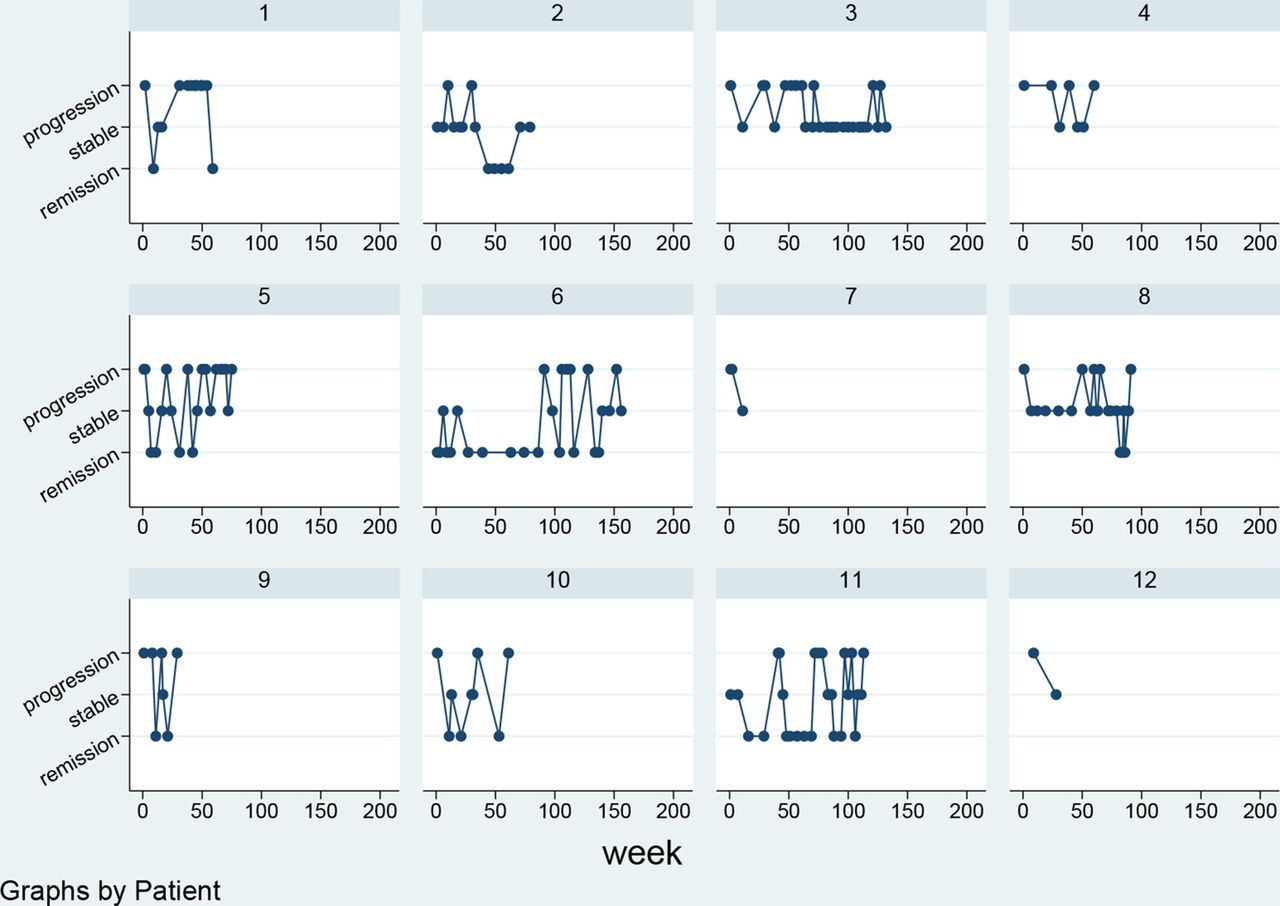

Patients living longer with incurable cancer cycle through (multiple) periods of remission, stability, and progression of the disease, as shown in Figure 1. Being hopeful after positive scan results, and being disappointed and scared after negative scan results, means that patients may constantly need to adapt their emotions. Being resilient, after having heard a positive or negative scan result, may facilitate a healthy fighting spirit to fight for life.

What people fight for may change along with the fluctuations in emotions people experience during the disease trajectory and how they remain resilient. Following the three components through which resilience is often distinguished — 1) the presence of adversity/risk; 2) positive adaptation or avoidance; and 3) protective factors or resources to facilitate effective adaptation in reaction to adversity19 — it could be argued that in understanding what constitutes a healthy fighting culture, the concept of fighting needs to be broadened to a certain extent.

Although we encourage a healthy fighting culture, as in fighting for life, the concept of fighting for life can be broadened, as in withholding some form of medication and/or starting with another form of medication may sometimes be more beneficial for the patient. Naturally, if the last phase of life is approaching, fighting for life in the context of the provision of anti-cancer treatment is not a topic of discussion anymore; their deteriorating situation may bring acceptance and preparation for death. Or, to put it into the words of Atul Gawande: ‘People with incurable cancer can do very well for a long time after diagnosis. […] They don’t feel sick. […] Eventually, it (the disease) makes itself known, turning up in the lungs, or in the brain, or in the spine. […] From there, the decline is often relatively rapid; death occurs later but the trajectory remains the same.’ 20

Having good examples of people in the patient’s close environment who fought healthily while receiving anti-cancer treatment as well as other optimistic people close by can assist the patient to fight healthily themselves.21 Apart from referring to the heroic nature of sports and the cancer story of a sportsperson to depict the nature of a cancer struggle, encouraging patients to do sports may be another good way to create the setting for a healthy fighting culture.22 Sports (either in an oncology training programme or as sport per se) could be an effective way to feel more relaxed (stress free) and in control of one’s life.23,24 Doing sports can facilitate a clear mind, increase energy (instead of cancer-related fatigue), and create a positive mood.

“We propose a definition of a ‘healthy fighting culture’ as a culture in which patients strive for optimal wellbeing for as long as possible.”

Conclusions

Over time, the definition and interpretation of fighting cancer has changed and the negative association in the context of aggressive overtreatment seems to have slowly disappeared. Yet, fighting cancer still seems to carry diverse meanings depending on the circumstances as well as patients’ and clinicians’ prior experiences, belief systems, and values. Medical developments with less burdensome treatment options, however, have awoken an intrinsic fighting drive among almost any oncology patient with a reasonable prognosis.

It could be argued that within health care, we should find ways to encourage patients to be aware of their inner strength to stimulate a healthy fighting spirit that will improve rather than worsen their wellbeing.25 Creating an atmosphere that puts someone’s mind at ease (for instance, by doing sports, laughing together,26 or doing nothing27) will probably enable patients and close relatives to more easily fight healthily.

Encouraging a healthy fighting spirit is probably partly based on trust and the right timing to intuitively stimulate patients to fight. This, to a certain extent, seems similar to the initiation of laughter, or the right timing of having specific conversations with patients who have an incurable form of cancer, which are often regarded as important elements of practicing medicine.

We therefore argue that a little touch of fighting will be beneficial for all: doctors will probably feel more inspired if they are able to guide and stimulate patients in this insecure disease phase of their life; patients, on the other hand, will probably have a higher chance of receiving personalised, appropriate treatment and care throughout their entire disease trajectory.

Funding

This article was funded by MSD and Ars Donandi.

References

1. Illich I. Limits to medicine. Medical nemesis: the expropriation of health. London: Marion Boyars, 1976.

2. Johnson LA, Ellis C. Chemotherapy in the last 30 days and 14 days of life in African Americans with lung cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021; 38(8): 927–931.

3. Pacetti P, Paganini G, Orlandi M, et al. Chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life of advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23(11): 3277–3280.

4. Kao S, Shafiq J, Vardy J, Adams D. Use of chemotherapy at end of life in oncology patients. Ann Oncol 2009; 20(9): 1555–1559.

5. Griffin AM, Butow PN, Coates AS, et al. On the receiving end. V: Patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer chemotherapy in 1993. Ann Oncol 1996; 7(2): 189–195.

6. Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland. NKR. https://iknl.nl/nkr (accessed 27 Sep 2024).

7. Clark D. Between hope and acceptance: the medicalisation of dying. BMJ 2002; 324(7342): 905–907.

8. van Ommen-Nijhof A, Retèl VP, van den Heuvel M, et al. A revolving research fund to study efficient use of expensive drugs: big wheels keep on turning. Ann Oncol 2021; 32(10): 1212–1215.

9. van Ommen-Nijhof A, Retèl VP, Konings IRHM, Sonke GS. [Clinical efficiency research with expensive drugs: doing more with less investment]. [Article in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2022; 166: D6527.

10. Byrne A, Ellershaw J, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Patients’ experience of cancer: evidence of the role of ‘fighting’ in collusive clinical communication. Patient Educ Couns 2002; 48(1): 15–21.

11. Antonaccio CM. On trauma, resilience, and survival-lessons from 15 years of pediatric cancer and remission. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6(12): 1866–1867.

12. Harrington KJ. The use of metaphor in discourse about cancer: a review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012; 16(4): 408–412.

13. Jecker NS, Pearlman RA. Medical futility. Who decides? Arch Intern Med 1992; 152(6): 1140–1144.

14. Schneiderman LJ. Defining medical futility and improving medical care. J Bioeth Inq 2011; 8(2): 123–131.

15. Björkhem-Bergman L. Overtreatment in end-of-life care: how can we do better? Acta Oncol 2022; 61(12): 1435–1436.

16. Orr RD, Genesen LB. Requests for “inappropriate” treatment based on religious beliefs. J Med Ethics 1997; 23(3): 142–147.

17. Hussaini Q, Smith TJ. Incorporating palliative care into oncology practice: why and how. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2021; 19(6): 390–395.

18. Buiting HM, Van Ark M, Dethmers O, et al. Complex challenges for patients with protracted incurable cancer: an ethnographic study in a comprehensive cancer centre. BMJ Open 2019; 9(3): e024450.

19. Molina Y, Yi JC, Martinez-Gutierrez J, et al. Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014; 18(1): 93–101.

20. Gawande A. Being mortal: illness, medicine, and what matters in the end. London: Profile Books, 2014.

21. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30(7): 879–889.

22. van Waart H, Buffart LM, Stuiver MM, et al. Adherence to and satisfaction with low-intensity physical activity and supervised moderate-high intensity exercise during chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28(5): 2115–2126.

23. Buiting HM, Sonke GS. Natural. J Surg Oncol 2024; 129(7): 1177–1178.

24. Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006; 174(6): 801–809.

25. Maté G, Maté D. Mind in the lead: the possibility of healing. In: Maté G, Maté D. The myth of normal: trauma, illness and healing in a toxic culture. London: Vermillion, 2022; 361–373.

26. Buiting HM, de Bree R, Brom L, et al. Adding shared laughter to optimise shared medicine. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(34_suppl): 43.

27. Kaye EC, Rockwell SL, Lemmon ME, et al. The art of saying nothing. Pediatrics 2022; 149(6): e2022056862.

Featured photo by Nadine Primeau (left) and Joe Yates (right) on Unsplash.