Victoria Silverwood is a GP and a Wellcome Trust Clinical PhD Fellow at Keele University. Her twitter handle is @v_silverwood

Simon Kitchen is the CEO of Bipolar UK.

Stuart Watson is a Clinical Senior Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist in Newcastle. His twitter handle is @StuartW13044383

David Kessler is a Professor of Primary Care Mental Health in Bristol.

Arun Kuruppath is a Specialist Registrar in General adult Psychiatry, Health Education England North East England.

Carolyn A. Chew-Graham is a GP in Manchester and Professor of General Practice Research at Keele University School of Medicine. She is on Twitter: @CizCG

What is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a severe mental illness characterised by significant and sometimes extreme changes in mood and energy, which go far beyond most people’s experiences of feeling a bit down or happy.1 There are over one million people with BPD in the UK,2 30% more than those with dementia and twice as many as those with schizophrenia. Millions more are impacted through close friends and family. Bipolar is usually divided into 2 categories: BPDI and BPDII. BPDI is more severe, particularly in terms of the elevated mood.

Epidemiology and aetiology

The reported estimated prevalence of BPD varies: One cross-sectional survey of >61,000 adults across 11 countries estimated lifetime prevalence of BPDI at 0.6% and lifetime prevalence of BPDII at 0.4% with a median onset of age 25.3 This compares to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis which estimates lifetime prevalence both to be higher at 1.06% lifetime prevalence for BPDI and 1.57% for BPDII.4 The aetiology of BPD is multi-factorial and not fully understood.5 Current evidence suggests that BPD may arise from the interaction between predisposing genetic factors and environmental risk factors such as exposure to stress or traumatic events, particularly childhood trauma.

Impact of BPD

Undiagnosed mania or hypomania can have serious consequences… with increased risk taking behaviours, disinhibition and involvement with the criminal justice system.

BPD can have negative consequences for patients and their surrounding support networks and people with BPD have a reduced life expectancy in comparison to the general population.6 There is increased risk of physical comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity, related to illness, lifestyle and drugs. The prevalence of self-harm has been estimated to affect 30-40% of patients with BPD; up to 20% of people with BPD die by suicide.6 Undiagnosed mania or hypomania can have serious consequences with episodes associated with increased risk taking behaviours, disinhibition and involvement with the criminal justice system.

When should clinicians suspect BPD?

On average, it takes 9.5 years from initial presentation of symptoms to have a formal BPD diagnosis.1 The Bipolar Commission report calls for earlier diagnosis and specialist support for everyone with BPD.1 The report stresses that this delay between initial presentation and diagnosis of BPD can lead to significant detrimental effects on individuals’ mental health and wellbeing, with an increased risk of suicide.6,7 Improving currents delays in diagnosis has been recommended as a research priority by the James Lind Alliance.8

There are two major classifications of BPD: Bipolar Disorder I (BPDI) and Bipolar Disorder II (BPDII), each with different diagnostic criteria. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSMV-5), are broadly similar but have subtle differences (see Box 1).

| Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for BPD | |

| Publication | Diagnostic criteriaa |

| BPDI | |

| DSM-5 | One manic episode (presenting with a combination of restlessness, euphoria, sleeplessness, risk taking, disinhibition and sometimes requiring inpatient care) without requirement for a major depressive episode. |

| ICD-11 | One episode of mania plus another episode of either hypomania or depression.

The diagnosis can be made based on evidence of a single manic or mixed episode. |

| BPDII | |

| Both DSM-5 and ICD-11 | One major depressive episode lasting at least 2 weeks.

One hypomanic episode (less severe and less functionally impairing than mania) lasting at least 4 days. NB: this differs from the elation people sometimes feel on recovering from depression. |

| aAll manic and hypomanic episodes in ICD-11 require as defining features: euphoria, irritability or expansiveness, and, increased activity or subjective experience of increased energy, plus ‘several’ (ICD-11) or three or more (DSM-5) of the following symptoms: increased talkativeness or pressured speech, flight of ideas, increased self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need of sleep, distractibility, impulsive reckless behaviour, increase in sexual drive, sociability or goal-directed activity. | |

UK studies of primary care populations suggest that many people with BPD are misdiagnosed, usually as having depression, leading to an increase in morbidity as a result. 9 In general, a manic episode lasting seven days suggests BPDI whereas a hypomanic episode lasting 4 days or more indicates a diagnosis of BPDII is more likely. Where patients present with intense emotional dysregulation, even if short lived, in the context of pervasive interpersonal difficulties clinicians should consider the possibility of personality disorder.9

When adults present in primary care with depression, particularly if the depression isn’t responding to treatment, GPs should consider the possibility of BPD and ask about previous periods of racing thoughts, over-activity or disinhibited behaviour. If racing thoughts, overactivity or disinhibited behaviour has previously been present and an episode has lasted for 4 days or more, GPs should consider whether this is evidence of a hypomanic episode and thus consider referral for a specialist mental health assessment. If a diagnosis of BPD is considered in primary care, it should be confirmed by specialist mental health services. 10

How are people with BPD managed?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guidance 185 ‘Bipolar disorder: assessment and management’ outlines current best practice recommendations for the management of BPD. Treatment options for BPD depression are usually medication and/or psychological therapies. 10 NICE recommends that it is important to optimise a mood stabiliser medication,10 usually Lithium, occasionally Sodium Valproate. Clinicians may also consider adding either Quetiapine or Olanzapine if needed, with Lamotrigine as a second line option. There is debate about the effectiveness and the risk of switch to mania with antidepressant medication in BPD and – other than fluoxetine in combination with olanzapine – these drugs are not recommended.10

A recent Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) review in December 2022 considered advice from the independent Commission on Humans Medicines (CHM) which reviewed the clinical safety of the prescription of Valproate. The current CHM advice is that Valproate should not be prescribed for any individual under the age of 55 unless two specialists independently determine that there is no other available safe and/or tolerated treatment. This is due to the teratogenicity of Valproate if taken during a pregnancy and due to the possible risk of impaired fertility in males.11

Educating patients and supporting them to recognise the early symptoms of a BPD relapse reduces the risk of relapse.

With regards to psychological therapies for bipolar depression, NICE guideline CG185 outlines two options.10 The first is to offer an intervention that has been developed specifically to manage BPD; the second is to offer a high‑intensity psychological intervention (such as CBT, interpersonal therapy or behavioural couples therapy) in line with recommendations in the NICE guideline NG222 on depression: (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222/documents/addendum-appendix-37). Educating patients and supporting them to recognise the early symptoms of a BPD relapse reduces the risk of relapse. It is acknowledged that accessing such care can be challenging due to limited availability and NICE calls for further development of such services.

There is also evidence that group psychoeducation, allowing people with bipolar to meet others experiencing similar problems, has benefits in BPD, but this may not be routinely available.

Key messages for clinicians in primary care

- The recent Bipolar UK report ‘Bipolar Minds Matter: Quicker diagnosis and specialist support for everyone with bipolar’ highlights the importance of timely diagnosis for people with BPD, as delays in diagnosis lead to increased morbidity and mortality for people with BPD

- GPs should remain alert to the possibility of a BPD diagnosis when:

- a patient presents with a depressive episode;

- a patient does not improve with antidepressants; and

- a patient presents with an obvious manic episode

- When BPD is suspected, referral to psychiatry is essential

- Bipolar UK provide a range of information about services at bipolaruk.org

Resources for patients:

Resources for healthcare professionals:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-4840895629

https://www.bipolaruk.org/bipolarcommission

Key findings of the 2021 bipolar commission include:

- More than a million people live with bipolar in the UK

- More than five million friends and family are significantly affected by a loved one’s bipolar

- Bipolar costs the UK economy £20 billion a year – 17% of the burden of disease for mental illness

- Someone with bipolar takes their own life every day

- 10% of our community said they had attempted to take their own life in the last six months

- More than half of people with bipolar have been hospitalised due to their bipolar

- 44% of people with bipolar are obese

- People with bipolar die 10-15 years earlier than the general population

References

- Bipolar UK. Bipolar Minds Matter Quicker diagnosis and specialist support for everyone with bipolar. 2022. https://www.bipolaruk.org

- McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. (eds.) (2016) Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital.

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(3): 241–251.

- Clemente AS, Diniz BS, Nicolato R, et al. Bipolar disorder prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Braz J Psychiatry 2015; (2): 155–161.

- Rowland TA, Marwaha S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2018; 8(9): 251.

- Chan JKN, Tong CCHY, Wong CSM, et al. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost in bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2022; 221(3): 567–576.

- Staudt Hansen P, Frahm Laursen M, et al. Increasing mortality gap for patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder—A nationwide study with 20 years of follow-up. Bipolar Disord 2019; 21(3): 270–275.

- The James Lind Alliance. Description of final workshop to set research priorities for Bipolar. 2016. shorturl.at/cnFST (accessed 16 Mar 2023).

- Hughes T, Cardno A, West R, et al. Unrecognised bipolar disorder among UK primary care patients prescribed antidepressants: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66(643): e71.

- NICE. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management Guidance. Clinical guideline [CG185]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185 (accessed 16 Mar 2023).

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Update on MHRA review into safe use of valproate. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/update-on-mhra-review-into-safe-use-of-valproate (accessed 16 Mar 2023).

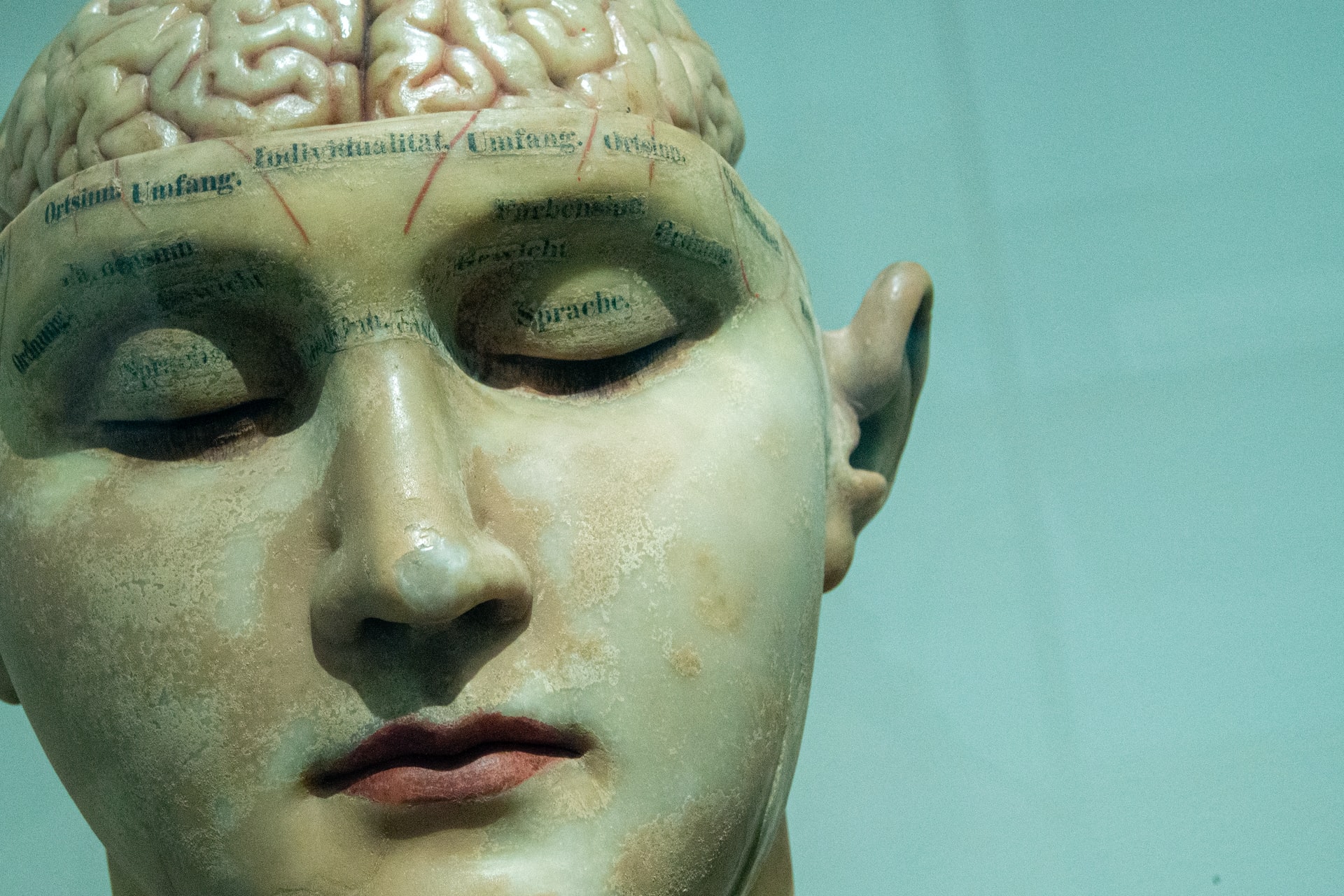

Featured photo by David Matos on Unsplash.