Nigel Masters is a retired General Practitioner.

Nigel Masters is a retired General Practitioner.

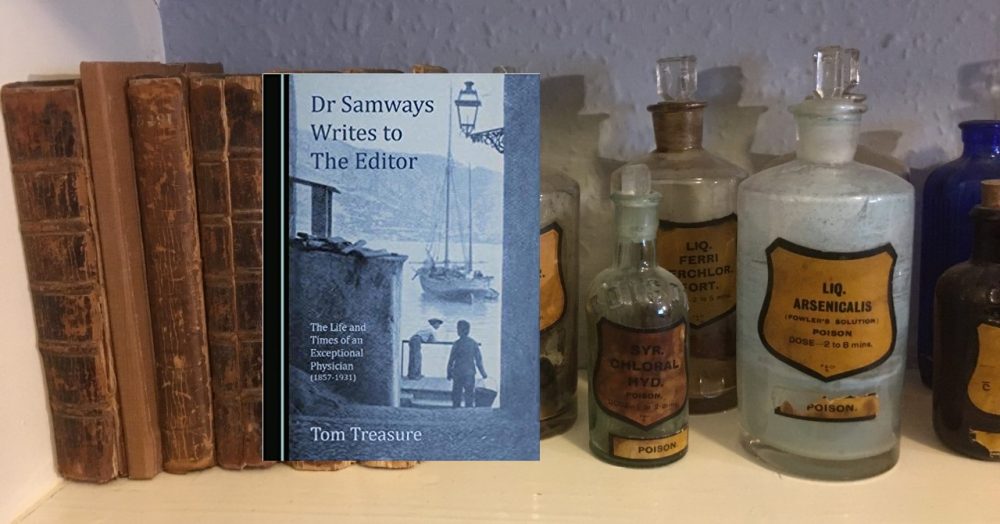

This biography of a scientifically minded general practitioner is a remarkable story, both of the tenacity of the medical author who tracked down the scientific writings of this unknown doctor and also the window to medical life and practice in the late 1800 to the early 1900 which it provides.

Tom Treasure, a retired cardiac surgeon biographer, gathered the historical material over thirty years. His interest was triggered by a letter written by Dr Samways predicting successful surgery in rheumatic mitral stenosis fifty years before it became accepted practice. The thirty chapters in the book are usefully standalone so can be dipped in easily to explore one’s own interests. They delve deeply in places exploring relevant historical medical topics and even the academic milieu of that time.

Dr Samways had “a high-flying undergraduate career studying physics in Cambridge, undertaking postgraduate research in Zurich, and lecturing in physiology as a fellow at St John’s College.” His studies abroad were focused on the electrophysiology of nerves. Most medical schools now look favourably on such postgraduate applicants as they can bring an added maturity and wider insights to their medical course. He qualified at Guy’s Hospital London in 1891.

Nevertheless, his career as a Guy’s Hospital Physician was derailed by contracting presumed lung tuberculosis from the post-mortem room while studying mitral stenosis specimens. There were no effective treatments for consumption at this time, so travel to warmer climes was widely advocated. Decades earlier the poet and Guy’s medical student John Keats had been advised to journey to Italy to prolong his consumptive life but died in Rome in 1821 aged twenty-five.

There were no effective treatments for consumption …. so travel to warmer climes was widely advocated.

This harbour town on the French Italian border was feted for its lemon growing and wonderful climate. Indeed, Dr Samways did recover here in 1894 and stopped coughing up blood and spent the rest of his life overwintering here and acting as a general medical practitioner to the wealthy British patients who could afford to spa here. He even met his future wife at Monaco who had recently lost her young husband from some unnamed condition.

The first world war resulted in a prolonged stay in England deployed as an anaesthetist and hospital doctor to the war wounded in a Military Hospital in Exeter. While working there he wrote about the management of deep war wounds and the safety of chloroform anaesthesia. Thus, he became in modern parlance: a GP with special interests.

Dr Samways would regularly write letters to the Editors of the Lancet and British Medical Journal taking to task many notable doctors of the time and describing his own scientific views on many subjects. Such doctors included the general practitioner turned Cardiologist James Mackenzie.

Samways’s … letters show both his scientific approach to disease management but also his care and concern for his patients.

This is a beautiful book for those visiting our medical history and the author should be congratulated on the detail he has been able to find on a remarkable unknown general medical practitioner who clearly satisfied the RCGP motto Cum Scientia Caritas.

Featured book

Dr Samways writes to the Editor: The Life and Times of an Exceptional Physician (1857-1931). Tom Treasure. Pub: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2021 ,293pp, £61.99, ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6915-7

* The French town of Menton was spelled “Mentone” in the 19th century.

Featured picture by David Misselbrook